Author: Isuna Hasekura

Author: Isuna Hasekura

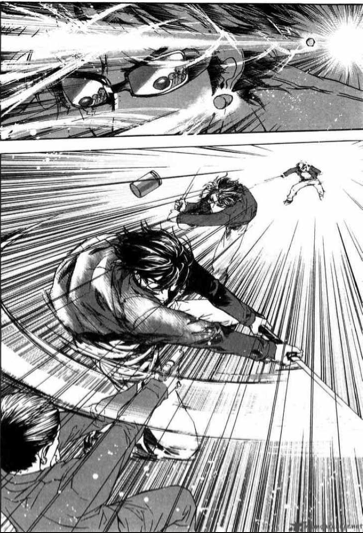

Illustrator: Jyuu Ayakura

Translator: Paul Starr

U.S. publisher: Yen Press

ISBN: 9780316245463

Released: April 2013

Original release: 2008

Town of Strife I is the eighth volume in Isuna Hasekura’s light novel series Spice & Wolf, illustrated by Jyuu Ayakura. The previous volume, Side Colors, was actually a collection of three side stories; Town of Strife I picks up the story immediately following Spice & Wolf, Volume 6. As indicated by its title, Town of Strife I is the first part of a two-volume story, a first for Spice & Wolf. Town of Strife I was originally published in Japan in 2008. Paul Starr’s English translation of the novel was released by Yen Press in 2013. Spice & Wolf is a series that I have been enjoying much more than I thought I would. Although I wasn’t particularly taken with most of Side Colors, I was interested in getting back to the main story again with Town of Strife I.

Having had quite the adventure on the Roam River, Kraft Lawrence, a traveling merchant, and Holo the Wisewolf, a centuries-old spirit in the form of a young woman, have finally made their way to the port town of Kerube with a new companion in in tow–Col, a young student they encountered along the river. Together the three of them are following a curious rumor: a search is on for the bones of a northern town’s guardian deity. Many people think the story is some far fetched fairytale, but Lawrence, Holo, and Col know very well that there could be some truth behind the rumors. Upon their arrival at Kerube Lawrence seeks the aid of Eve, a former noblewoman and a skilled merchant in her own right. He’s been burned once before in his dealings with her, but Eve’s impressive network of connections may be their best chance of finding the bones.

One of the things that I have always enjoyed about Spice & Wolf is the relationship and developing romance between Lawrence and Holo. By this point in the series, Lawrence has lost some of his awkwardness when it comes to Holo. While I suppose this means he’s grown as a character, I do miss the more easily embarrassed Lawrence. With the addition of Col to the mix, the dynamics of Holo and Lawrence’s relationship has also changed. Their battles of wits and their good-natured bickering and teasing which once seemed so natural now feel forced as if the two of them are putting on some sort of performance for the boy. More often than not, Holo and Lawrence are verbally sparring for show in Town of Strife I and it’s not nearly as entertaining. Ultimately I do like Col (everyone in Spice & Wolf likes Col), but his presence in the story is somewhat distracting.

Not much happens in Town of Strife I; it mostly seems to be setting up for the second volume in the story arc. Hasekura promises that Lawrence will get to be “really cool” in the next volume and Town of Strife I does end on a great cliffhanger, but I’m not sure that I’m actually interested in finding out what happens. Unfortunately, the series has finally lost its charm for me. The characters know one another so well and their conversations are so cryptic that the story is difficult to follow. The narrative lacks sufficient detail and explanations leaving readers to puzzle out the characters’ motivations and actions. This has always been the case with Spice & Wolf but what makes it particularly frustrating in Town of Strife I is that the volume doesn’t even have a satisfying ending and doesn’t stand well on its own. Hasekura claims that he needed two volumes to tell this particular story, but considering how tedious much of Town of Strife I is, I’m not convinced.