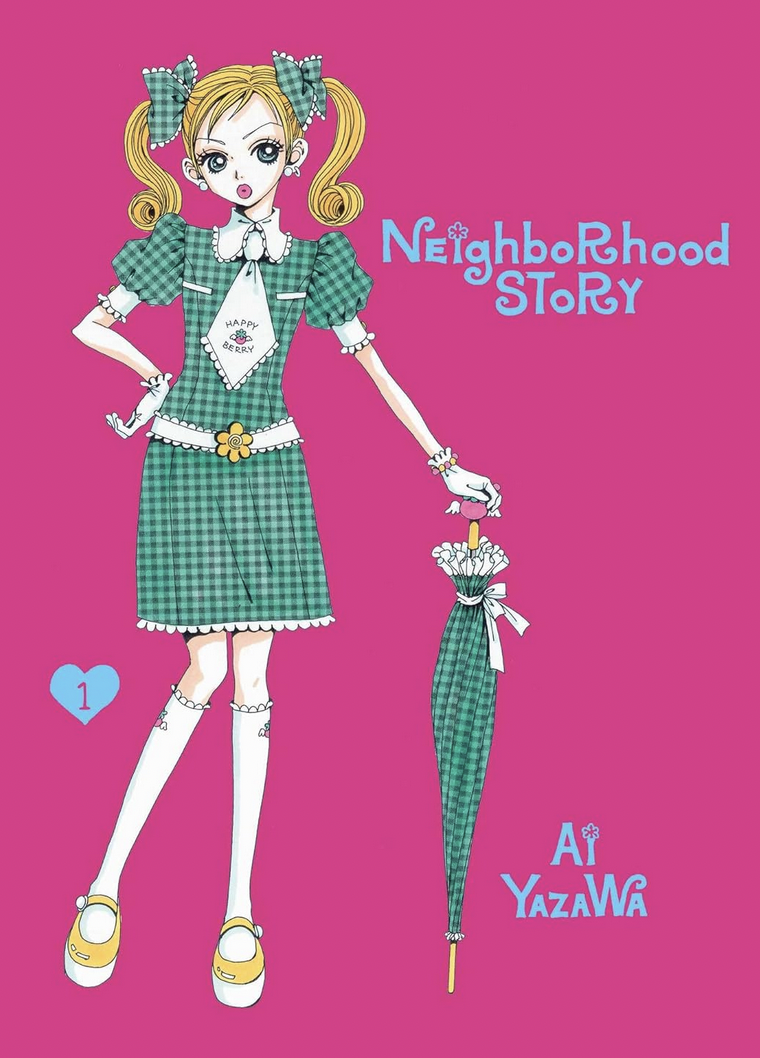

Neighborhood Story Volume 1 by Ai Yazawa

Neighborhood Story is a manga I’ve been aware of for a long time, because the characters drop in on Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss, but I never thought it would actually be translated into English! I’m glad that Viz has licensed this shoujo classic. Mikako is an aspiring fashion designer who has a ton of personality packed into her tiny body. Tsutomo is the boy next door. They’ve been constant childhood companions, and many of their surrounding family and friends seem to expect that they’ll end up together.

Mikako is a little suspicious about Tsutomo’s inadvertent womanizing ways, as his similarity to a pop idol causes him to be fascinating to random girls. Tsutomo wonders if he and Mikako are so close that they aren’t ever really going to experience life without some time apart. They seem obviously perfect for each other and yet sometimes oblivious to their own emotions in ways that are utterly realistic for teenagers experiencing the first stirrings of something that might be love. Mikako is a force to be reckoned with, and as their extended group of friends start gathering together to pursue their creative dreams, I’m looking forward to experiencing again that combination of love story and artistic ambition that Ai Yazawa writes so well.

While the art isn’t as polished as Yazawa’s later series, her spindly characters and their fashion forward style contribute to the creative community that surrounds and supports Mikako and Tsutomo. Reading Neighborhood Story feels nostalgic in the best way, and I’m glad I finally have a chance to experience it.

Attention manga shoppers!

Attention manga shoppers!

This year’s

This year’s

Like a well-listened to lullaby, I find myself in front of the keyboard with a manga volume beside me. And so, the song starts again. Fitting that I chose a story set in a fairy-tale world to return with.

Like a well-listened to lullaby, I find myself in front of the keyboard with a manga volume beside me. And so, the song starts again. Fitting that I chose a story set in a fairy-tale world to return with.