For thirteen years, I lived with Grendel, a smart, stubborn Australian shepherd who treated me and my husband like a pair of unruly sheep. She woke us up at 5:45 am every day, herded us to the park, and marched us around until we were exhausted. She nipped our ankles when we left for work—we weren’t supposed to leave the farm, I guess—and had strong preferences about everything, from which routes we walked to which brand of kibble we bought. When she wasn’t trying to bend us to her will, she applied her formidable intelligence to foraging snacks; she had a black bear’s talent for opening containers of peanut butter, Tums—you name it. I loved her dearly, but I admit that there were times when I fantasized about living with a dog who wasn’t so determined to run our house.

With my current commute, I can’t own the happy-go-lucky dog of my dreams, but I can do the next best thing: read about one. That’s where Lovely Muco! comes in. It’s a gag manga inspired by the real-life relationship between Komatsu, a professional glass blower, and Muco, his exuberant Shiba Inu. In every chapter, Muco makes a discovery—that her nose is shiny, or that Komatsu isn’t a dog—and becomes so consumed with excitement that she ends up in trouble. Muco’s reactions to everyday situations bring out her inner Gracie Allen; she’s less dim than dizzy, viewing the world with the peculiar logic of a canine enthusiast. A trip to the vet, for example, leads her to wax rhapsodic about the cone of shame, which she views as a stylish accessory, rather than an encumbrance. Even when her injury starts to itch, Muco remains convinced that she looks cool, going so far as to imagine how Komatsu would look with his own cone.

As much as I love Muco’s antics, my favorite storyline focuses on Komatsu, who hires his pal Ushiko to design him a website. Ushiko uses the tools that you’d expect—a digital camera, a laptop—but Komatsu’s reactions to these technologies seem more appropriate for someone who’d just spent the last 20 years living off the grid than someone making a living in modern-day Japan. His child-like wonder mirrors the way Muco approaches just about everything in her life, from tennis balls to car rides—a neat inversion of their usual roles.

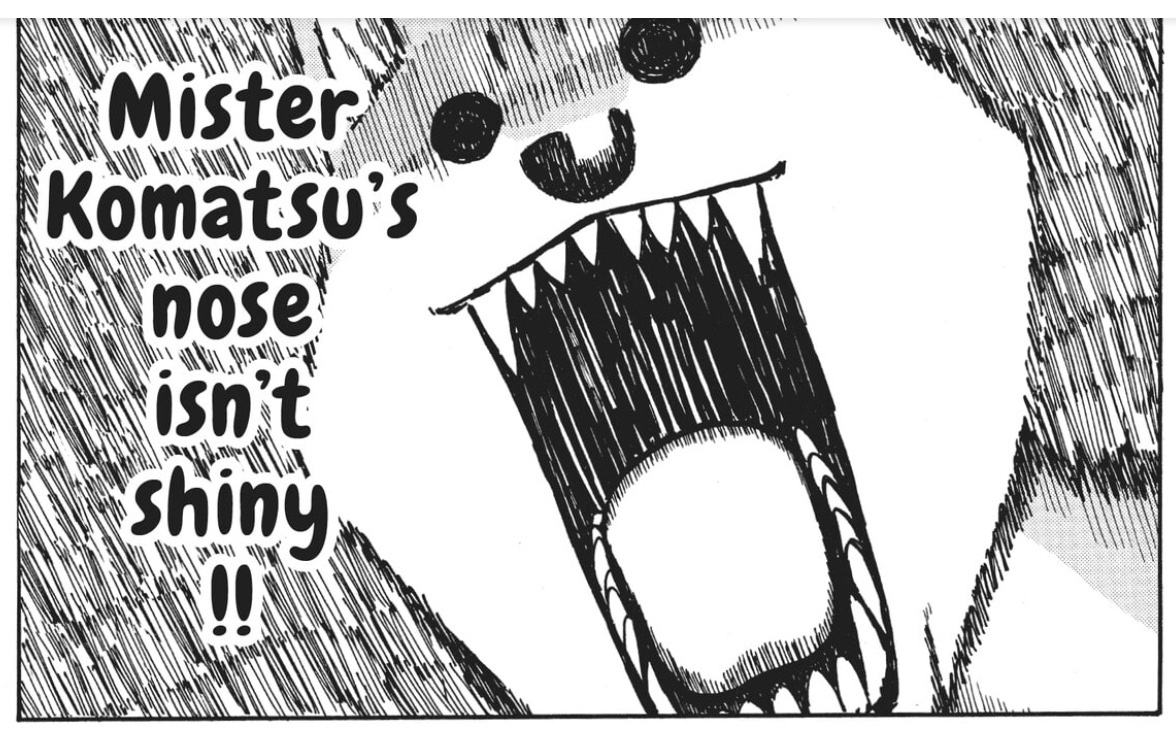

Takayuki Mizushina’s artwork plays a big role in making their owner-dog dynamic funny. Mizushina’s approach is more gestural than literal, distilling each character, human or animal, to a set of bold lines and basic shapes. Muco, for example, bears only a passing resemblance to a Shiba Inu, as Mizushina draws her head like a stop sign with triangular ears. That hexagonal shape, however, provides Mizushina an ideal frame for Muco’s facial expressions:

And while plenty of other manga artists use this same device to express extreme emotion, Mizushina really captures the essence of how an excited dog reacts to new things in its environment; you can almost hear Muco barking whenever she has an epiphany.

What I like best about Lovely Muco, though, is that Muco’s thought process isn’t like Grommit or Snoopy’s. She’s not building wild contraptions or fantasizing about being a World War I flying ace; she’s just trying to make sense of the people and things around her. Her fascination with ordinary objects is a nice reminder that part of living with a dog—or any sentient creature—is recognizing how strange and interesting our world must seem to them, and taking pleasure in their curiosity and enthusiasm. Recommended.

PS: If you just can’t get enough shiba inu hijinks, you can follow the real-life Muco’s exploits on Twitter. (Hat tip to @debaoki for the link.)

LOVELY MUCO! THE HAPPY DAILY LIFE OF MUCO AND MR. KOMATSU, VOL. 1 • ART AND STORY BY TAKAYUKI MIZUSHINA • TRANSLATED BY CASEY LEE • KODANSHA COMICS 220 pp. • RATED 10+ (SUITABLE FOR READERS OF ALL AGES)

Attention manga shoppers!

Attention manga shoppers!