I usually start The Manga Review with industry news, but the announcement that Pitchfork was being folded into GQ has been on my mind this week. Whatever its faults, Pitchfork was one of the few websites still offering idiosyncratic, thought-provoking music reviews in 2023. Their critics could be gratuitously nasty—Jeremy Larson’s scathing assessment of Greta Van Fleet’s Anthem of the Peaceful Army comes to mind—but I always appreciated their efforts to promote obscure artists, hold the music industry to account, and challenge the critical consensus around established acts like Sonic Youth. (Brett DiCrescenzo predicted their 2000 album NYC Ghosts & Flowers “will be heard in the squash courts and open mic nights of deepest hell.”)

We’ve seen something similar happen in the comics sector with CBR and Comics Alliance, two once-independent sites that were acquired by big media companies. For a brief moment, it seemed as if the acquisitions were a positive development, but over time, CBR and Comics Alliance’s owners phased out the in-depth journalism and serious criticism that defined the original sites in favor of click-bait articles, press releases, and toothless reviews. There are still a handful of great sites covering manga and anime—Anime News Network, The Beat, WWAC—but there’s less meaningful criticism overall, and fewer distinctive voices writing manga reviews. We need more of those spaces; they provide a meaningful alternative to the group-think and fan orthodoxies that prevail on Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Reddit, and the industry-cozy reviews on platforms such as CBR. Maybe this is the year YOU start your own site.

NEWS ROUNDUP

Everybody wants to go to Anime NYC 2024 it seems, as three-day passes for the annual convention sold out less than two hours after they went on sale… Yen Press published a list of its top-selling books of 2023… Azuki just announced four new titles… Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron is setting box office records around the world… and the Fifth Circuit just ruled that Texas cannot require book sellers to use a rating system when selling materials to libraries and schools. Brigid Alverson has the full details on this ongoing case.

ESSAYS AND PODCASTS

Tony Yao explains why My Girlfriend’s Child is a refreshingly honest look at the challenges facing teen parents in Japan and elsewhere. [Drop-In to Manga]

Kevin Lainez lists his five favorite manga of 2023. [Comic Book Review]

And speaking of best-of lists, Jordan and David announce the winners of the Shonen Flop Awards for 2023, “the most prestigious awards in canceled manga.” [Shonen Flop]

Also looking back on 2023 are Ray and Gee, who name their five favorite debuts of 2023. [Read Right to Left]

The Manga Machinations team devote their latest podcast to a discussion of Eldo Yoshimizu’s Hen Kai Pan. [Manga Machinations]

ICYMI: Lisa De La Cruz offers five recommendations for readers who share her love of BL manhwa. [The Wonder of Anime]

REVIEWS

Adam Symchuk gives high marks to Since I Could Die Tomorrow, an all-too-rare manga about a career woman in her forties… D. Morris declares Shiro Moriya’s Soloist in a Cage a promising debut… WWAC assembles an all-star team of reviewers to recommend manga and comics worth reading… and the gang at Beneath the Tangles offers an assortment of short and sweet reviews.

- 7Fates: Chakho, Vol. 1 (Noemi10, Anime UK News)

- Backstage Prince, Vol. 1 (Daniel Van Gorder, The Fandom Post)

- Bergamot & Sunny Day (Lisa De La Cruz, The Wonder of Anime)

- Chitose Is in the Ramune Bottle, Vol. 5 (Josh Piedra, The Outerhaven)

- Choujin X, Vol. 4 (Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Fairy Tail: 100 Years Quest, Vols. 13-14 (Demelza, Anime UK News)

- Fly Me to the Moon, Vol. 21 (Josh Piedra, The Outerhaven)

- The Horizon, Vol. 1 (A Library Girl’s Familiar Diversions)

- The Horizon, Vol. 3 (Adam Symchuk, Asian Movie Pulse)

- I’m Quitting Heroing, Vol. 4 (Antonio Miereles, The Fandom Post)

- Jujutsu Kaisen, Vol. 5 (Sara Smith, The Graphic Library)

- Kaiju No. 8, Vol. 7 (Sara Smith, The Graphic Library)

- Neighborhood Story, Vol. 1 (Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Super Morning Star, Vol. 2 (Sarah, Anime UK News)

- Tokyo Aliens, Vol. 5 (Demelza, Anime UK News)

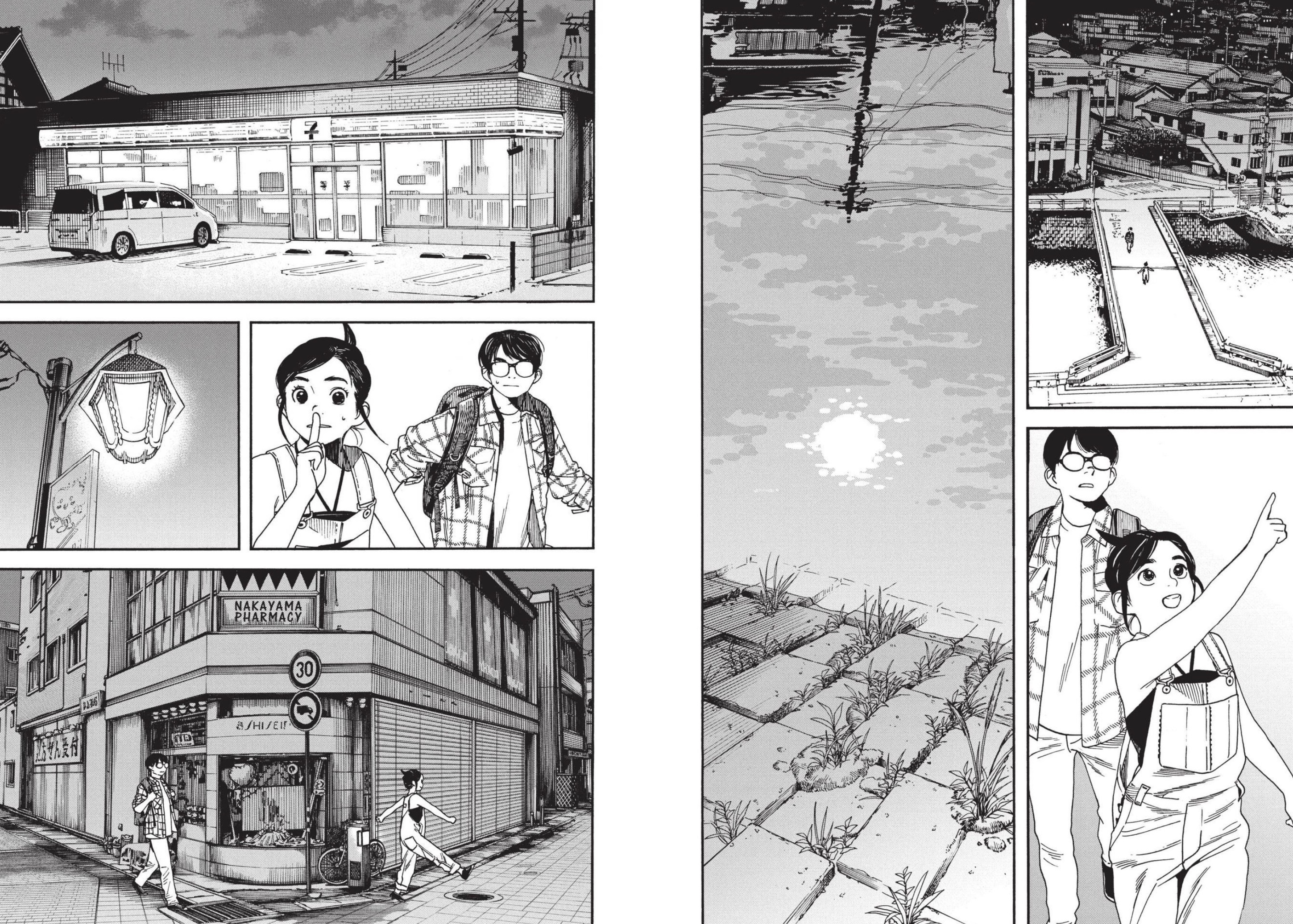

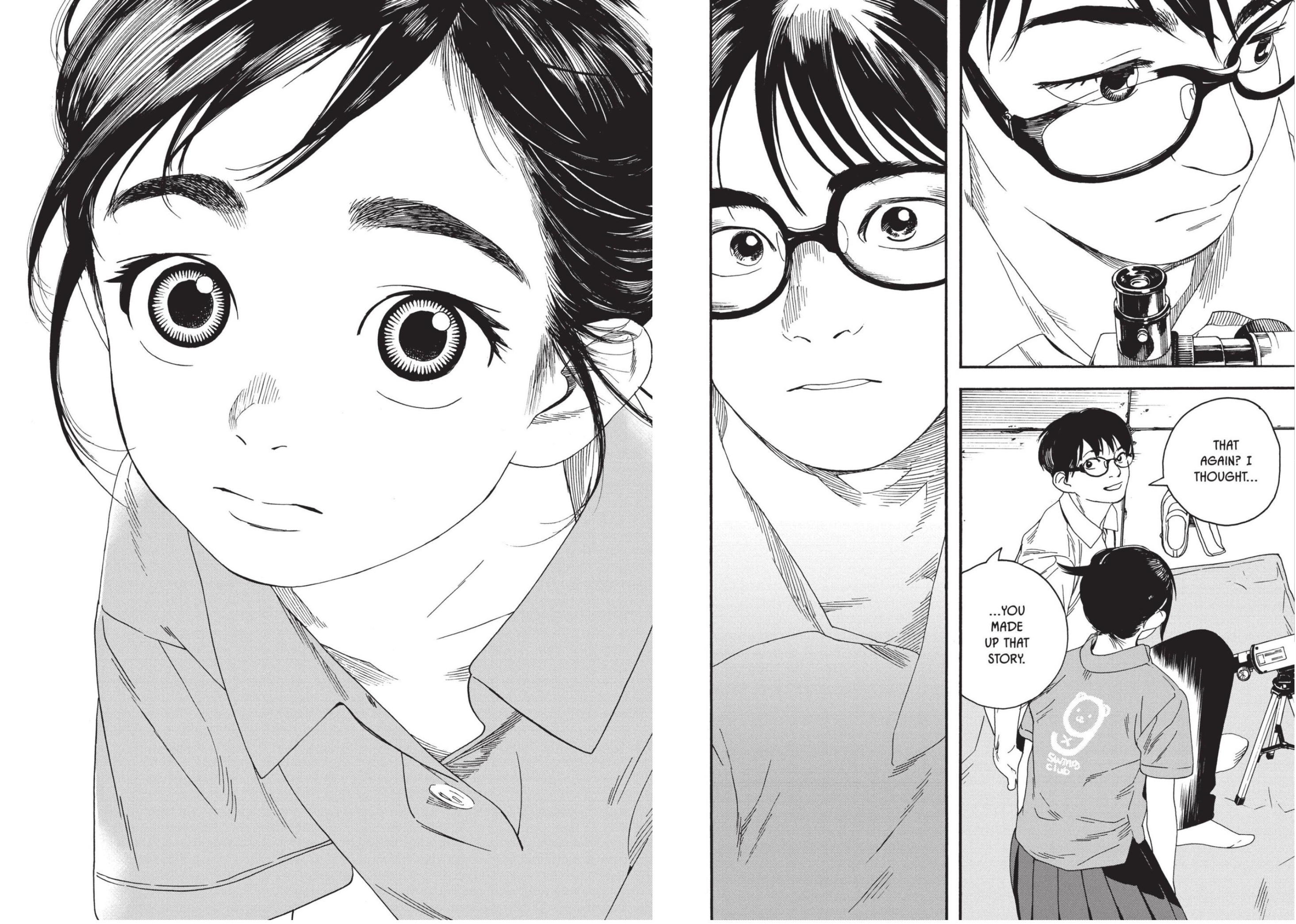

- Tokyo These Days, Vol. 1 (Tom Batten, School Library Journal)

- Tokyo These Days, Vol. 1 (Marcus Orchard, Sequential Planet)

- Touge Oni: Primal Gods in Ancient Times, Vol. 2 (Kate O’Neil, The Fandom Post)

- Touring After the Apocalypse, Vols. 3-4 (Adam Symchuk, Asian Movie Pulse)

- Virgin Love, Vol. 1 (Demelza, Anime UK News)

- We Can’t Do Plain Love, Vols. 1-2 (Ilgin Side Soysal, The Beat)

- Whisper Me a Love Song, Vol. 1 (Sara Smith, The Graphic Library)

- Witch Life in a Micro Room, Vol. 1 (Adam Symchuk, Asian Movie Pulse)

- Zom 100: Bucket List of the Dead, Vol. 12 (Boston Bastard Brigade)

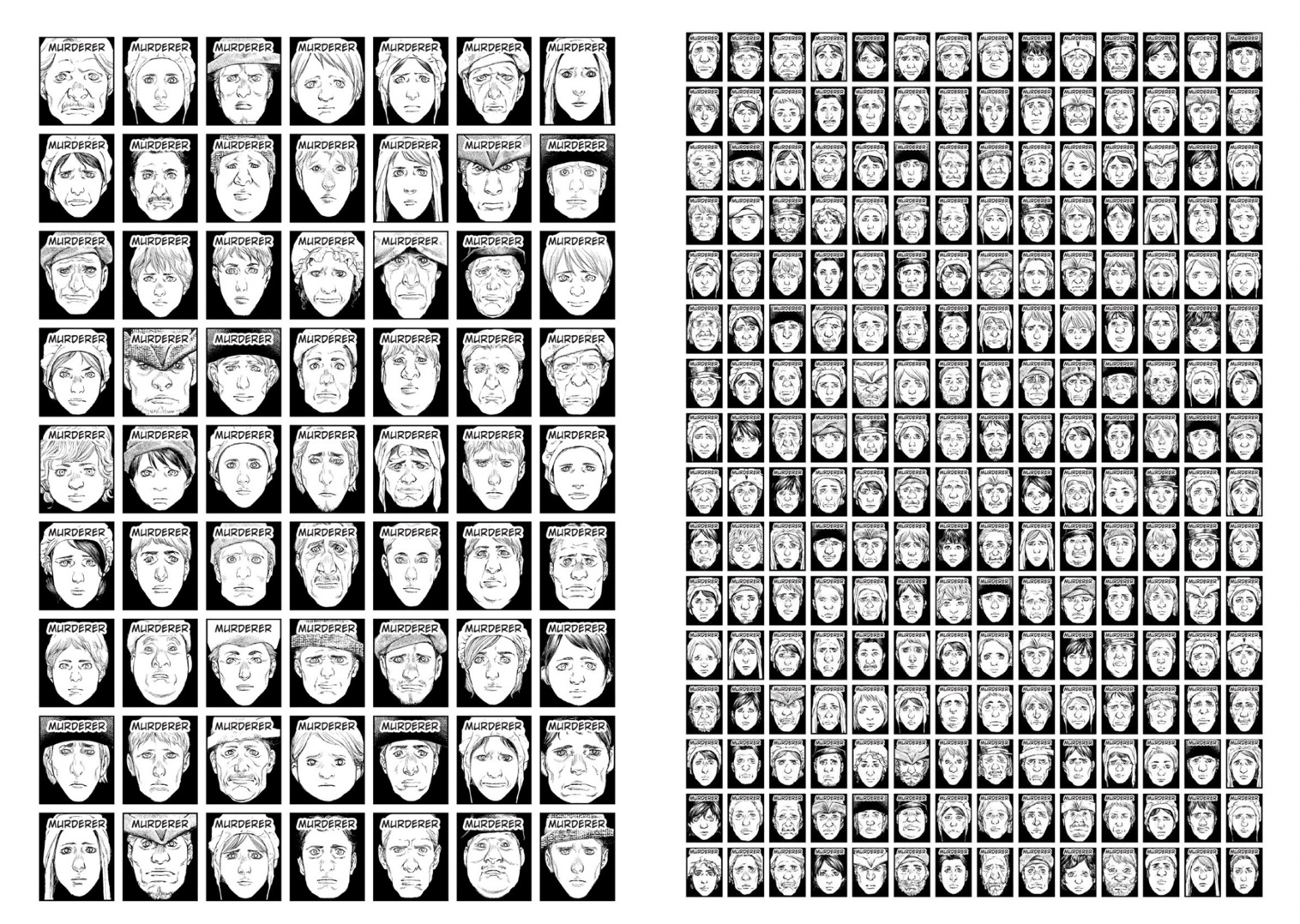

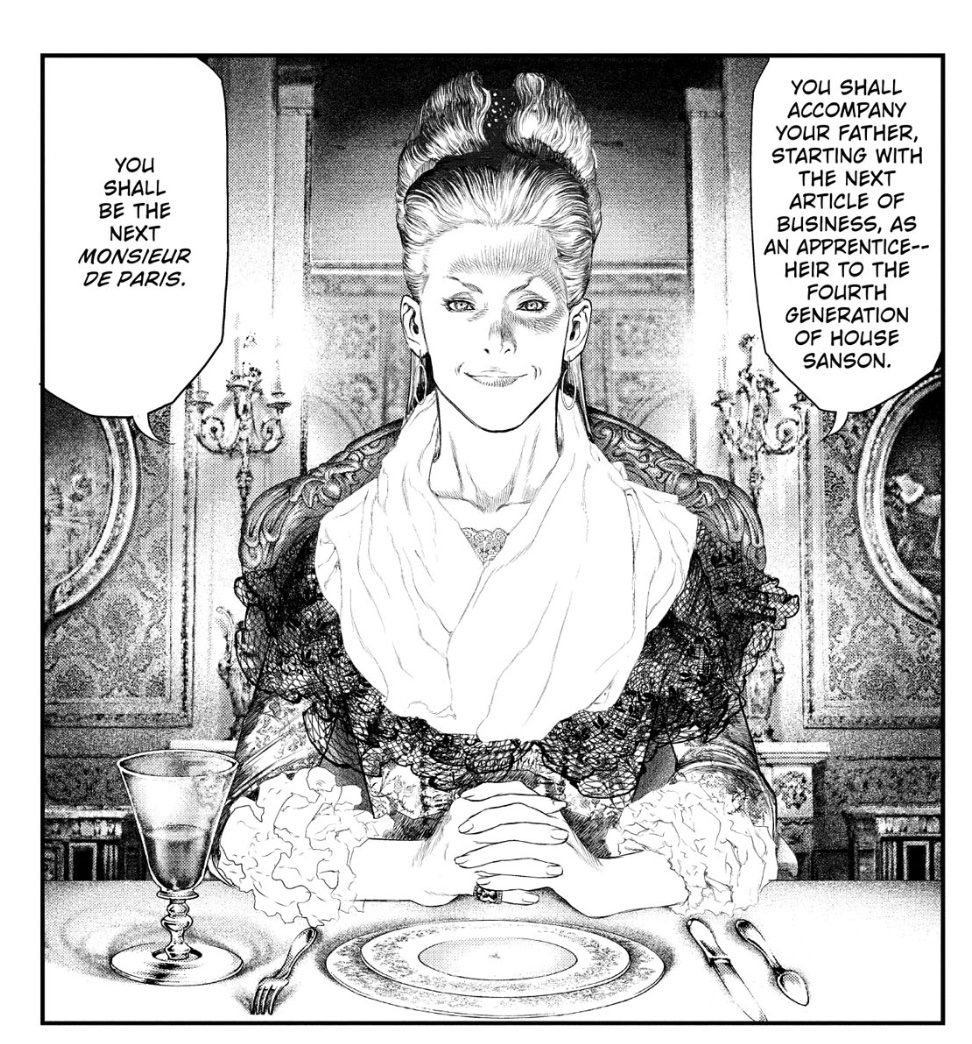

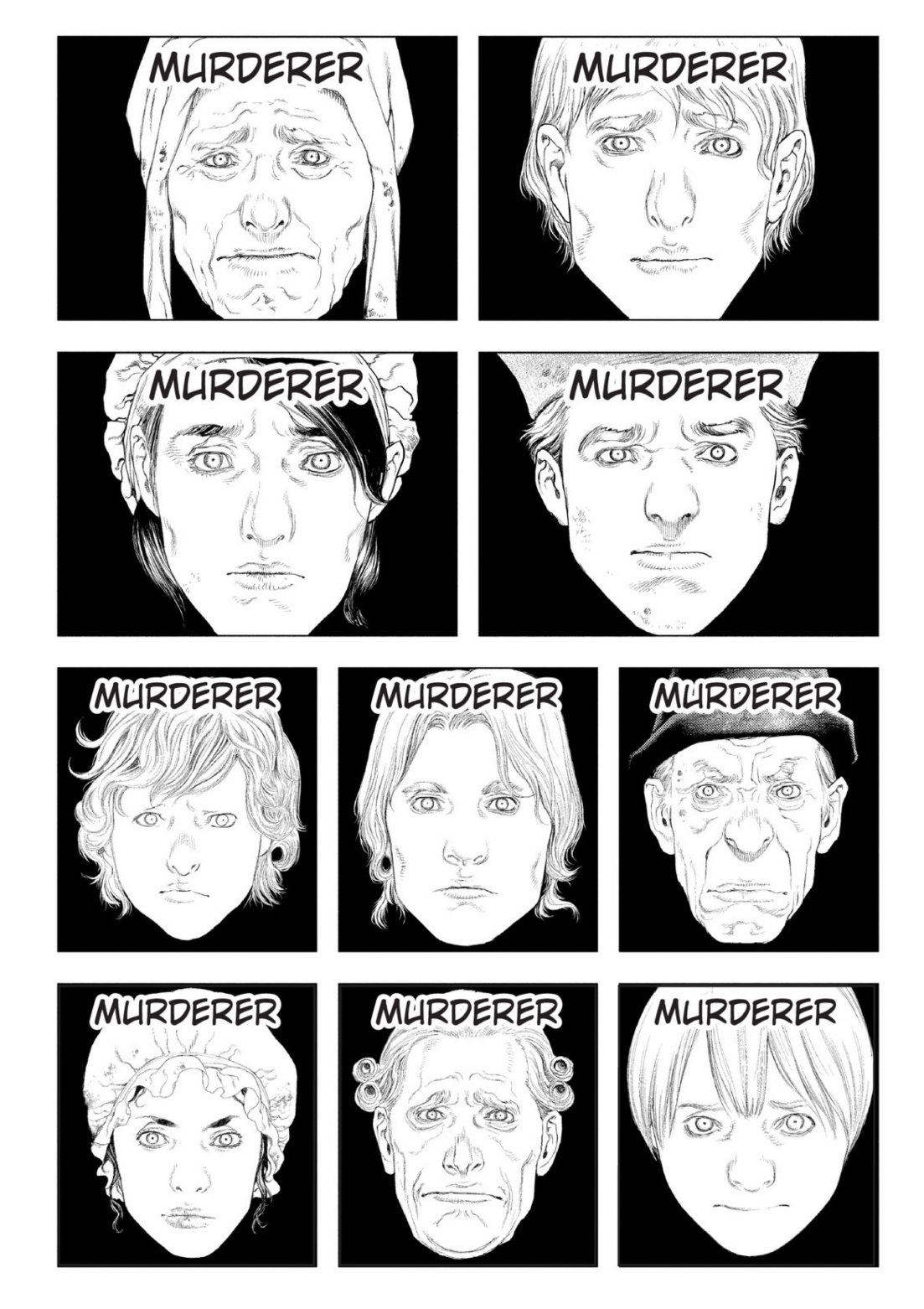

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces:

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces: