Of all the famous works of literature to get the Classics Illustrated treatment, Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human is an odd choice. Its protagonist is Oba Yozo, a tortured soul who never figures out how to be his authentic self in a society that places tremendous emphasis on hierarchy, self-restraint, and civility. Over the course of the novel, he binges, gambles, seduces a string of women, joins a Communist cell, attempts suicide, and succumbs to heroin addiction, all while donning the mask of “the farcical eccentric” to conceal his “melancholy” and “agitation” from the very people whose lives he ruins.

Though the novel is filled with incident, its unreliable narrator and relentless interiority make it difficult to effectively retell in a comic format, as Junji Ito’s adaptation demonstrates. Ito’s No Longer Human is largely faithful to the events of Dazai’s novel, but takes Dazai’s spare, haunting narrative and transforms it into a phantasmagoria of sex, drugs, and death. In his efforts to show us how Yozo feels, Ito leans so hard into nightmarish imagery that the true horror of Yozo’s story is overshadowed by Ito’s artwork—a mistake, I think, as Ito’s drawings are too literal to convey the nuance of what it means to exist, in Peter Selgin’s words, in a state of “complete dissociation… yet still capable of feeling.”

In Ito’s defense, it’s not hard to see what attracted him to Dazai’s text; Yozo’s narration is peppered with the kind of vivid analogies that, at first glance, seem ideally suited for a visual medium like comics. But a closer examination of the text reveals the extent to which these analogies are part of the narrator’s efforts to beguile the reader; Yozo is, in effect, trying to convince the reader that his mind is filled with such monstrous ideas that he cannot be expected to function like a normal person. There’s a tension between how Yozo describes his own reactions to the ordinary unpleasantness of interacting with other people, and how Yozo describes the impact of his behavior on other people—a point that Ito overlooks in choosing to flesh out some key events in the novel.

Nowhere is that more evident than in Yozo’s brief affair with Tsuneko, a destitute waitress. After hitting rock bottom financially and emotionally, Yozo persuades her to join him in a double suicide pact. Dazai’s summary of what happens is shocking in its brevity and matter-of-factness:

As I stood there hesitating, she got up and looked inside my wallet. ‘‘Is that all you have?” Her voice was innocent, but it cut me to the quick. It was painful as only the voice of the first woman I had ever loved could be painful. “Is that all?” No, even that suggested more money than I had — three copper coins don’t count as money at all. This was a humiliation more strange than any I had tasted before, a humiliation I could not live with. I suppose I had still not managed to extricate myself from the part of the rich man’s son. It was then I myself determined, this time as a reality, to kill myself.

We threw ourselves into the sea at Kamakura that night. She untied her sash, saying she had borrowed it from a friend at the cafe, and left it folded neatly on a rock. I removed my coat and put it in the same spot. We entered the water together.

She died. I was saved.

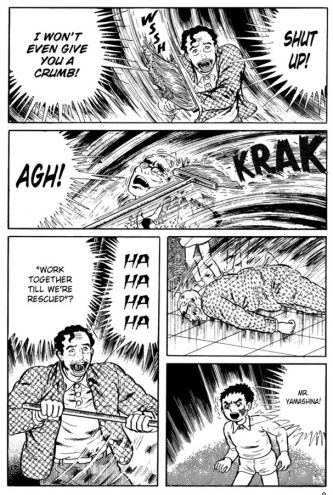

As Ito recounts this event, however, Tsuneko’s death is caused by a poison so painful to ingest that she collapses in a writhing heap, eyes bulging and tongue wagging as if she were in the throes of becoming a monster herself. Yozo’s reaction to the poison, by contrast, is to plunge into a hallucinatory state in which a parade of ghostly women mock and berate him, an artistic choice that suggests Yozo feels shame and guilt for his actions—and a reading of Dazai’s text that makes Yozo seem more deserving of sympathy than he does in Dazai’s novel:

Throughout this vignette, Yozo’s contempt for Tsuneko creeps into the narrative, even as he assures the reader that she was the first woman he truly loved. Yozo’s disdain is palpable, as is evident in the way he off-handedly introduces her to the reader:

I was waiting at a sushi stall back of the Ginza for Tsuneko (that, as I recall, was her name, but the memory is too blurred for me to be sure: I am the sort of person who can forget even the name of the woman with whom he attempted suicide) to get off from work.

Only a few episodes capture the spirit of Dazai’s original novel, as when Yozo’s father gives an inept speech to a gathering of businessmen and community leaders. Ito skillfully cross-cuts between three separate conversations, allowing us to step into Yozo’s shoes as he eavesdrops on the attendees, servants, and family members, all of whom speak disparagingly about each other, and the speech. By pulling back the curtain on these conversations, Ito helps the reader appreciate the class and power differences among these groups, as well as revealing that this episode was a turning point for Yozo: the moment when he first realized that adults maintain certain masks in public that they discard in private. Though such a moment would undoubtedly trouble a more observant child—one need only think of Holden Caulfield’s obsession with adult “phoniness”—this discovery plunges Yozo into a state of despair, as he cannot imagine how anyone reconciles their public and private selves in a truthful way.

Ito also wisely restores material from Dazai’s novel that other adaptors—most notably Usamaru Furuya—trimmed from their versions. In particular, Ito does an excellent job of exploring the dynamic between Yozo and his classmate Takeichi, the first person who sees through Yozo’s carefully orchestrated buffoonery:

Just when I had begun to relax my guard a bit, fairly confident that I had succeeded by now in concealing completely my true identity, I was stabbed in the back, quite unexpectedly. The assailant, like most people who stab in the back, bordered on being a simpleton — the puniest boy in the class, whose scrofulous face and floppy jacket with sleeves too long for him was complemented by a total lack of proficiency in his studies and by such clumsiness in military drill and physical training that he was perpetually designated as an ‘‘onlooker.” Not surprisingly, I failed to recognize the need to be on my guard against him.

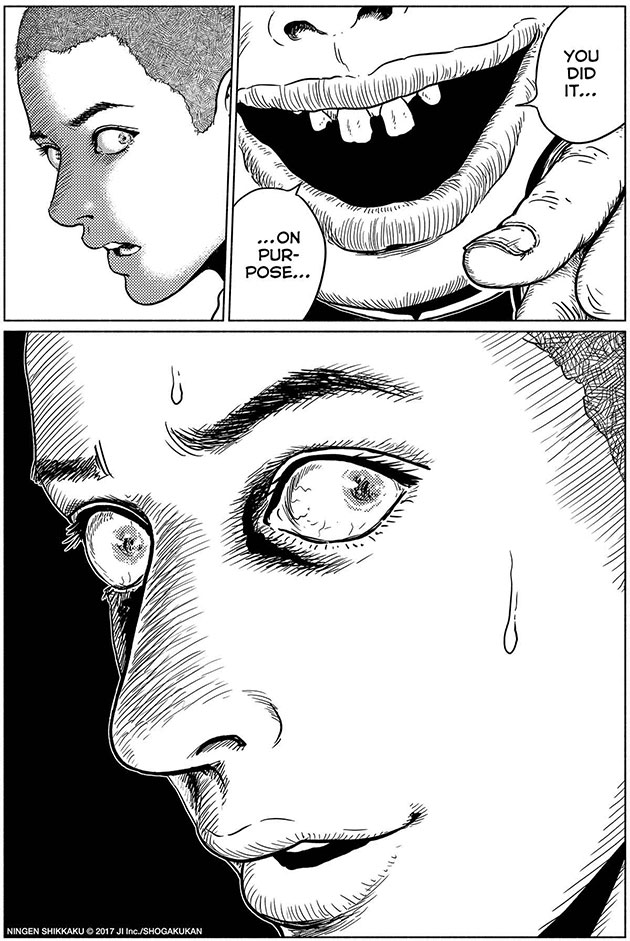

As one might guess from this passage, Yozo’s terror at being discovered is another critical juncture in the novel. “I felt as if I had seen the world before me burst in an instant into the raging flames of hell,” he reports, before embarking on a campaign to win Takeichi’s trust by “cloth[ing his] face in the gentle beguiling smile of the false Christian.” Though Ito can’t resist the temptation to draw an image of Yozo engulfed in hell fire, most of Yozo’s fear is conveyed in subtler ways: a wary glance at Takeichi, an extreme close-up of Yozo’s face, an awkwardly placed arm around Takeichi’s shoulder:

What happens next in Ito’s version of No Longer Human, however, is indicative of another problem with his adaptation: his decision to add new material. In Dazai’s novel, Takeichi simply disappears from the narrative when Yozo moves to Tokyo for college, but in Ito’s version, Yozo cruelly manipulates Takeichi into thinking that Yozo’s cousin Setchan is in love with him—a manipulation that ultimately leads to Takeichi’s humiliation and suicide. That violent death is followed by a gruesome murder, this time prompted by a love triangle involving Yozo, his “auntie,” and Setchan, who becomes pregnant with Yozo’s child. Neither of these episodes deepen our understanding of who Yozo really is; they simply add more examples of how manipulative and callous he can be, thus blunting the impact of the real tragedy that unfolds in the late stages of his story.

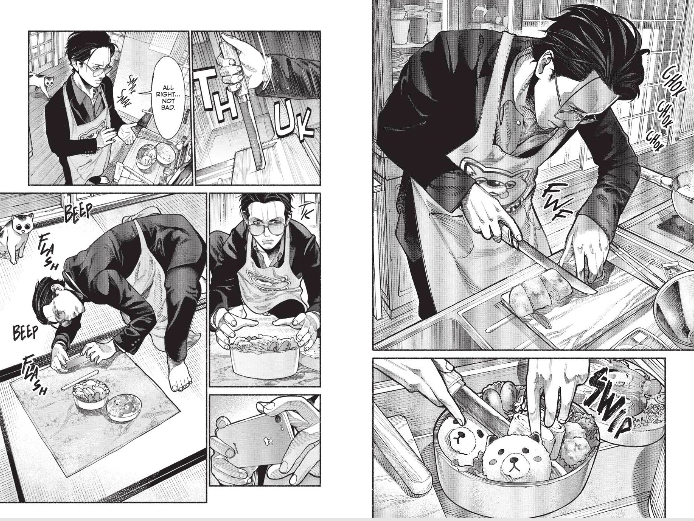

Ito’s most problematic addition, however, is Osamu Dazai himself. Ito replaces the novel’s original framing device with the events leading up to Dazai’s 1948 suicide, encouraging us to view No Longer Human as pure autobiography through reinforcing the parallels between Dazai’s life and Yozo’s. And while those parallels are striking, the juxtaposition of the author and his fictional alter ego ultimately distorts the meaning of the novel by suggesting that the story documents Dazai’s own unravelling. That’s certainly one way to interpret No Longer Human, but such an autobiographical reading misses Dazai’s broader themes about the burden of consciousness, the nature of self, and the difficulty of being a full, authentic, feeling person in modern society.

VIZ Media provided a review copy. You can read a brief preview at the VIZ website by clicking here. For additional perspectives on Junji Ito’s adaptation, see Serdar Yegulalp‘s excellent, in-depth review at Ganriki.org, Reuben Barron‘s review at CBR.com, and MinovskyArticle’s review at the VIZ Media website.

JUNJI ITO’S NO LONGER HUMAN • ORIGINAL NOVEL BY OSAMU DAZAI • BASED ON THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY DONALD KEENE • TRANSLATED AND ADAPTED BY JOCELYNE ALLEN • VIZ MEDIA • RATED M, FOR MATURE AUDIENCES • 616 pp.