Earlier this week, Shueisha and MediBang launched MANGA Plus Creators, a platform for English and Spanish-speaking artists to publish their own original manga. Anyone who uploads their work to the platform is automatically entered in a contest that comes with a cash prize and distribution through the MANGA Plus and Shonen Jump+ apps. (The site will use likes, favorites, and total views to determine the winners of each month’s contest, as well as input from Shueisha’s editorial staff.) While that sounds like a good deal, artists should read the fine print before submitting their work; the artist retains basic intellectual property rights to their creation, but must allow MediBang and Shueisha “to use the contents the User submitted and published on the Service, MANGA Plus Creators by SHUEISHA for free with the purpose of advertising and promoting the Service, the Related website, and the Related service.” Caveat emptor!

FEATURES AND PODCASTS

Comics scholar Paul Gravett just posted a thoughtful list of twenty-six art books and graphic novels slated for a November 2022 release, among them They Were Eleven, Synasthesia: The Art of Aya Takano, and The Boxer. [Paul Gravett: The Blog at the Crossroads]

Alicia Haddick files a report from the Sailor Moon 30th Anniversary exhibition, now on display at the Sony Music Roppongi Museum in Tokyo. The show runs through the end of 2022. [Crunchyroll]

Speaking of exhibitions, Tokyo’s Seibu department store announced that it will be sponsoring a 40th anniversary celebration of Shuichi Shigeno’s professional debut. The show will feature artwork from Bari Bari Densetsu, MF Ghost, and, of course, Initial D. [Otaku USA]

Megan D. highlights some problematic imagery on the cover of Tokyopop’s Peremoha: Victory for Ukraine anthology. [Twitter]

And speaking of Tokyopop, the publisher is actively participating in the Soar with Reading Initiative, an organization that “provides free books to children to address the issue of ‘book deserts,’ areas with limited access to age-appropriate books.” [ICv2]

If you’re in the mood for love, Honey’s Anime has a helpful list of ten great romance manga. [Honey’s Anime]

Kawaii alert: the Mangasplainers dedicate their latest episode to Konami Kanata’s Chi’s Sweet Home. [Mangasplaining]

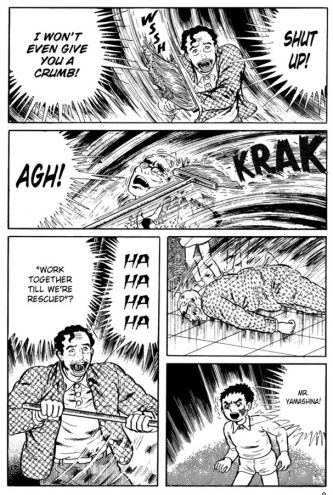

Helen Chazan posts a thoughtful meditation on Kazuo Umezz‘s preoccupation with childhood trauma and abuse, as evident in The Drifting Classroom, The Cat-Eyed Boy, and Orochi. “This is Umezz’s interest: teasing out, for entertainment purposes, the dissonance between the idealized family and the actual resentments a child feels within their family,” she explains. “Mother is an ideal of nationhood, the soil from which you grew. Mother is also the woman who scolded you, humiliated you, controlled your existence from home while your father worked long hours. How can both stories be true?” [The Comics Journal]

Also worth a look: Caitlin Moore’s essay about My Brain is Different: Stories of ADHD and Other Developmental Disorders. Moore notes that author Monzusu “sought out the stories of ordinary people with experiences similar to her own, eventually turning some of them into a memoir manga. In doing so, she offered neurodivergent people like her a rare chance to tell their own stories in their own words, when most of the world would rather talk over us, and created a tool to help people understand people like us.” [Anime Feminist]

REVIEWS

Sean Gaffney and Michelle Smith weigh in on the latest installments of Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End, In/Spectre,and Knight of the Ice, while the crew at Beneath the Tangles offer a medley of short manga reviews.

New and Noteworthy

- Chalk-Art Manga: A Step-By-Step Guide (Harry, Honey’s Anime)

- Kimono Jihen, Vol. 1 (Rebecca Silverman, Anime News Network)

- A Nico-Colored Canvas, Vol. 1 (Rebecca Silverman, Anime News Network)

- Princess Knight: Omnibus Edition (darkstorm, Anime UK News)

- A Returner’s Magic Should Be Special, Vol. 1 (Noemi10, Anime UK News)

- SINoAlice, Vol. 1 (Rebecca Silverman, Anime News Network)

- The Tunnel to Summer, The Exit of Goodbyes: Ultramarine, Vol. 1 (Renee Scott, Good Comics for Kids)

- Your Treacle Affects at Night (Rebecca Silverman, Anime News Network)

Complete and Ongoing Series

- Don’t Toy With Me, Miss Nagatoro, Vol. 11 (King Baby Duck, Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Excel Saga (Megan D., The Manga Test Drive)

- Kuishinbo (Krystallina, Daiyamanga)

- New York, New York, Vol. 2 (Sarah, Anime UK News)

- Otherside Picnic, Vol. 2 (Sandy F., Okazu)

- Sasaki and Miyano, Vol. 6 (Sarah, Anime UK News)

- The Splendid Work of a Monster Maid, Vol. 3 (Demelza, Anime UK News)

- Yuri Is My Job!, Vol. 9 (Erica Friedman, Okazu)