This has been a relatively quiet week on the manga beat, so I’m going to lead off with a question: what are you reading? Is there a series that you wouldn’t hesitate recommend? A manga that looked promising but disappointed or, conversely, a manga that looked awful but turned out to be fun, interesting, or engrossing? Inquiring minds want to know!

NEWS AND VIEWS

As the eighth volume of The Yakuza’s Guide to Babysitting arrived in Japanese bookstores, publisher Micro Magazine announced that the series just reached an important milestone: one million volumes in circulation. [Otaku USA]

Another Wednesday, another passel of licensing announcements from Seven Seas: look for I Didn’t Mean to Fall in Love, My Girlfriend’s Child, and Please Go Home, Miss Akutsu! in 2023. [Seven Seas]

David Brothers leads a lively roundtable discussion of MOB PSYCHO 100, with an emphasis on its polarizing artwork. [Mangasplaining]

The reviewers at Honey’s Anime have compiled a list of their ten favorite historical manga, from Seven Shakespeares to Golden Kamuy. [Honey’s Anime]

Over at TCJ, Jon Holt and Teppei Fukuda have translated another essay by manga critic

REVIEWS

Justin and Krystallina agree: you should be reading My Happy Marriage. Over at Women Write About Comics, Masha Zhdanova praises Nagabe’s Blue Monotone for its low-key approach to depicting teenage romance. “Nagabe uses anthropomorphic animals to tell a story about a familiar theme: being ‘weird’ isn’t inherently bad, and differences between people should be celebrated instead of shamed,” she observes. “The fact that this love blossoms between two animal boys, both outcasts in different ways, helps make this theme clear.” Also worth a look is Paulina Pryzstupa’s thoughtful review of Look Back, a novella-length story from the creator of Chainsaw Man.

New and Noteworthy

- Atom: The Beginning, Vol. 1 (Charles Hartford, But Why Tho?)

- Blitz, Vol. 1 (Harry, Honey’s Anime)

- Cat + Gamer, Vol. 1 (Ashley Hawkins, Manga Librarian)

- The Geek Ex-Hit Man, Vol. 1 (Sakura Eries, The Fandom Post)

- Heaven’s Door: Extra Works (Onosume, Anime UK News)

- The Liminal Zone (King Baby Duck, Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Look Back (Brandon Danial, The Fandom Post)

- Ping-Pong Dash!, Vols. 1-5 (Krystallina, Daiyamanga)

- Romantic Killer, Vol. 1 (Joseph Luster, Otaku USA)

- Rooster Fighter, Vol. 1 (King Baby Duck, Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Sakamoto Days, Vol. 1 (Rai, The OASG)

- She, Her Camera, and Her Seasons, Vol. 1 (King Baby Duck, Boston Bastard Brigade)

- Wandance, Vol. 1 (Sarah, Anime Uk News)

- Yokohama Kaidaishi Kikou, Vol. 1 (Harry, Honey’s Anime)

Complete and Ongoing Series

- Crazy Food Truck, Vol. 2 (Christopher Farris, Anime News Network)

- Fly Me to the Moon, Vol. 13 (Josh Piedra, The Outerhaven)

- Imadoki! Nowadays (Megan D., The Manga Test Drive)

- Kubo Won’t Let Me Be Invisible!, Vol. 3 (Josh Piedra, The Outerhaven)

- Our Not-So-Lonely Planet Travel Guide, Vol. 3 (Sarah, Anime UK News)

- Ragna Crimson, Vol. 6 (Grant Jones, Anime News Network)

- Spy x Family, Vol. 8 (Rebecca Silverman, Anime News Network)

April sales figures are in, and

April sales figures are in, and

PINEAPPLE ARMY

PINEAPPLE ARMY About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima.

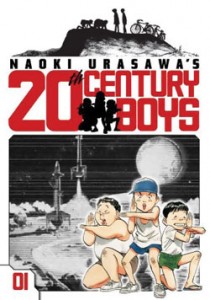

About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima. From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

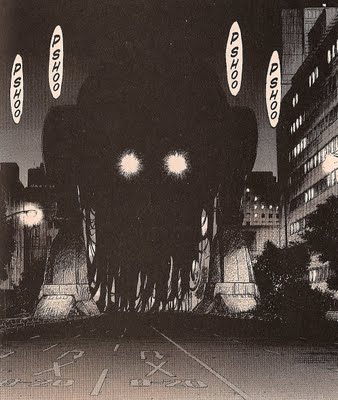

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.