First published in 1956, Black Blizzard is a juicy pulp thriller that will irresistibly remind Western readers of The 39 Steps, The Defiant Ones, and The Fugitive. The hero is twenty-five-year-old Susumu Yamaji, a down-on-his-luck pianist who stands accused of murdering the ringmaster of a traveling circus. The circumstantial evidence against him is so compelling that even Susumu — who was in a drunken stupor at the time — believes he did it. After surrendering to authorities, Susumu is handcuffed to hardened criminal Shinpei Konta, a middle-aged man who’s spent most of his adult life drifting in and out of jail. (When Susumu admits to his crime, Shinpei sniffs, “Just one? Tch! That’s nothing! I’ve been convicted five times. Twice for murder.”) An avalanche provides the shackled pair an opportunity to escape into a raging snowstorm, police hot on their trail.

Written in just twenty days, Black Blizzard unfolds at a furious clip, pausing only to allow Susumu a chance to tell Shinpei about his involvement with the circus. The two principals are more archetypes than characters, drawn in bold strokes, but the interaction between them crackles with antagonistic energy — they’re as much enemies as partners, roles that they constantly renegotiate during their time on the lam. Only in the final, rushed pages does manga-ka Yoshihiro Tatsumi falter, tidily resolving the story through an all-too-convenient plot twist that hinges on coincidence.

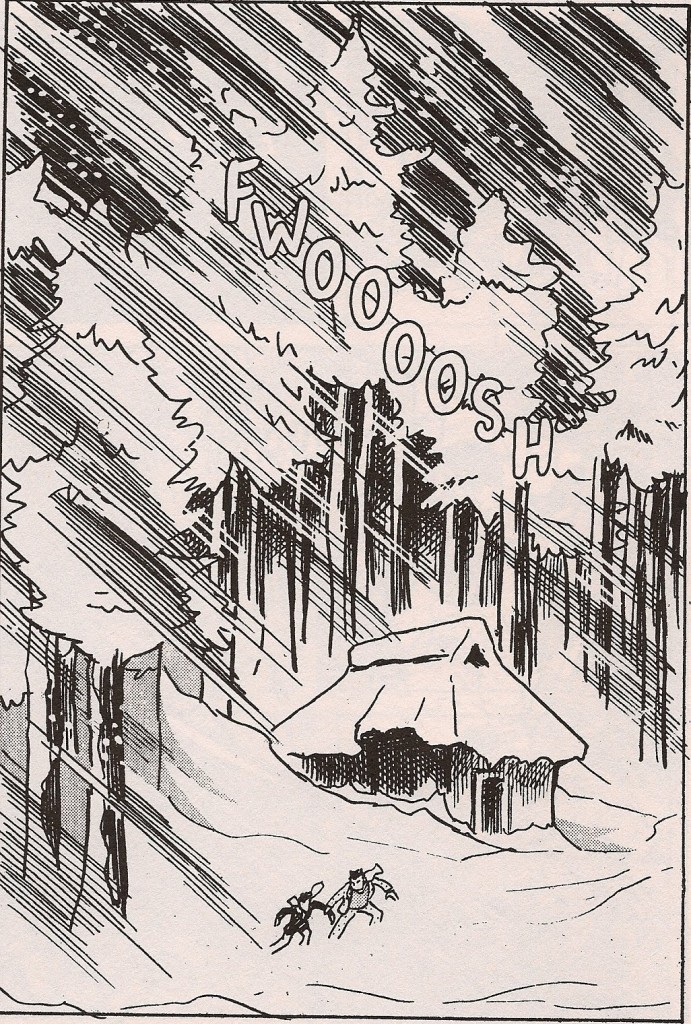

The plot may be pilfered from Manhunt — Tatsumi claims Mickey Spillane as an influence — but the art leaves a fresh impression. Tatsumi already had a substantial amount of work under his belt at the time he wrote Blizzard — seventeen novel-length stories, as well as several volumes’ worth of short ones — but was moving in the direction of what he called “manga that isn’t manga,” stories that exploited the medium’s capacity for representing action in a more dynamic, cinematic fashion. Black Blizzard is filled with slashing diagonal lines, dramatic camera angles, and images of speeding trains; it’s as if Giacomo Balla decided to try his hand at sequential art, filling the pages with as many signifiers of motion as he could muster without lapsing into abstraction:

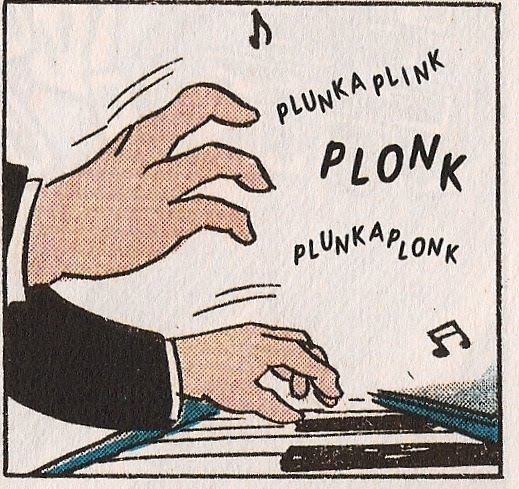

This kineticism extends to even the smallest gestures; in the very first panels, for example, we see a pair of hands banging out notes on a keyboard:

The composition couldn’t be simpler — just a few speedlines and sound effects convey the action — but these details, when coupled with the claw-like position of the hands, suggest the pianist’s extreme agitation, an impression confirmed just a few panels later when we first see Susumu’s sweat-drenched face.

Tatsumi’s regard for anatomy is, at times, careless; Susumu has Rachmaninoff-sized mitts, to judge from the awkward way in which his hands are drawn, while other cast members look stumpy, with grossly foreshortened legs. Yet for all the obvious flaws in his draftmanship, Tatsumi’s gestural approach to characterization proves well-suited to the material’s relentless pace, efficiently communicating each cast member’s personality, age, and plot function with a few artfully rendered lines and shapes. Shinpei, in particular, is a terrific creation, with a broad, sagging jaw and two thick, diagonal lines for eyebrows, making him a dead ringer for a jack-o-lantern.

Drawn & Quarterly has done a fine job of adapting Black Blizzard for Western readers, thanks, in large part, to a crisp translation by Akemi Wegmuller that captures the unique cadences of mid-century noir; one can almost imagine Shinpei referring to an attractive woman as a “tomato.” The volume also includes an interview with Tatsumi; read in tandem with “The Joy of Creation,” one of the later chapters in A Drifting Life, the interview sheds light on Tatsumi’s creative process as well as the work’s initial reception. Editor and designer Adrian Tomine has given Black Blizzard a retro-chic makeover, dying the trim yellow and boldly announcing the book’s price in the manner of a dime-store novel. It’s an attractive design (see above), but I can’t help wishing that Drawn and Quarterly had used Masami Kuroda’s original painting:

It’s a minor complaint, to be sure, but the original cover — to my mind, at least — is a closer expression of the story’s pulpy roots and futurism-tinged artwork.

That said, Black Blizzard is a welcome addition to the growing body of mid-century manga now available in English, providing an all-too-rare glimpse into the early stages of the gekiga movement. And while it lacks the visual and narrative polish of Tatsumi’s mature work, I’ll take the sweaty hyperbole of Black Blizzard over the dour verismo of The Push Man any day; Black Blizzard has a vital, improvisatory energy missing from Tatsumi’s later period, even though his command of the medium was clearly more assured in the 1960s and 1970s.

BLACK BLIZZARD • BY YOSHIHIRO TATSUMI • DRAWN & QUARTERLY • 132 pp. • NO RATING

PINEAPPLE ARMY

PINEAPPLE ARMY From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.