Welcome to another Manhwa Monday! We’re running late this week, but we’ve got some great review links to share.

Welcome to another Manhwa Monday! We’re running late this week, but we’ve got some great review links to share.

First off, at Soliloquy in Blue, Michelle Smith reviews volumes two and three of There’s Something About Sunyool, available now from NETCOMICS online.

“In the end, There’s Something About Sunyool offers a lot of crackalicious drama that is extremely fun to read. Volume two is a bit slow, as all of the bickering grows tiresome, but don’t let that dissuade you from continuing on to volume three, which is much better and ends on quite a cliffhanger. ”

Volume one is available in print now, with volume two set for release in September. Check out Michelle’s review for more.

Elswhere in reviews, at Manga Maniac Cafe, Julie takes a look at volume four of Sarasah (Yen Press). At Comic Book Bin, Chris Zimmerman reviews volume three of Jack Frost (Yen Press). Both Kristin Bomba (Comic Attack) and Charles Webb (Manga Life) check out Time and Again …

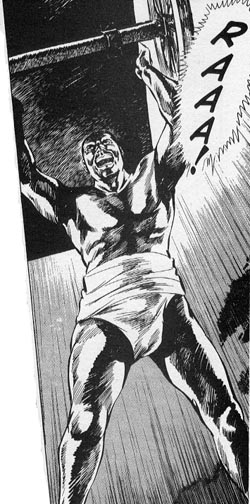

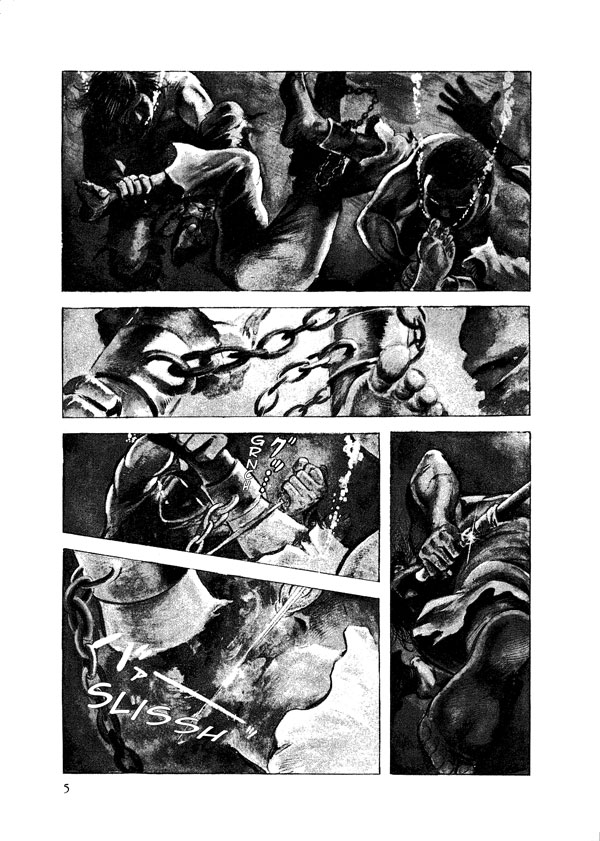

The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

Orange Planet, Vol. 1

Orange Planet, Vol. 1 Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1

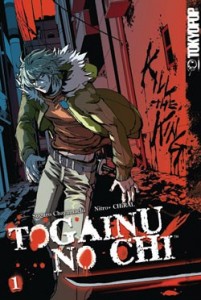

Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1 Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1

Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1