As I embarked on getting caught up on Gangsta, I found myself very grateful for the character bios and plot summaries in front of the volumes. The first couple volumes focused on the slightly more intimate lives of Alex as she meets and is taken in by the Handymen Worick and Nic inter cut with various scenes of violence, but the series is now headed into a full on gang war, and it is useful to be reminded of just who is who in the ever expanding cast of characters.

Gangsta Volume 4 by Kohske

The fourth volume deals with the personal problems of the characters as well as introducing more members of the sprawling underworld in the city of Ergastulum. The handymen are cleaning up after an attack, and Alex is distracted with memories of her younger brother. After shaking the dependency on the drugs she was previously addicted to, more of her normal memories are starting to come back, but she’s not yet able to recall the details of her past life. One of the things I like about this series is the artful way Kohske portrays her action scenes. Alex goes on an errand for the Handymen, and when she happens on a scene where another woman is being attacked, she grabs a stray piece of lumber and rushes in to defend a stranger without thinking of her own safety. Alex is about to get attacked herself, when on the next page a single panel of Nic in motion, mid-leap behind her attacker shows that the problem is being taken care of with almost frightening efficiency.

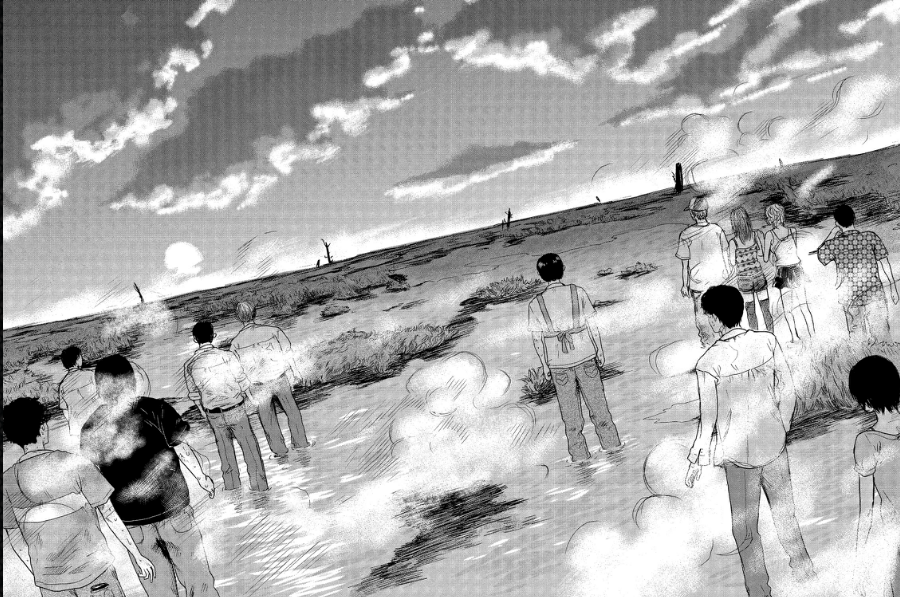

Alex and the Handymen go to a party thrown by the Cristiano Family, one of the weakest mafia families who is also the most charitable when it comes to taking care of Twilights who would otherwise not have a place to claim sanctuary. The head of the family is a tiny young girl named Loretta, who pragmatically surrounds herself with skilled bodyguards. An equally young twilight hunter shows up at the party and sets off a bloodbath. Another hunter names Erica appears, and while the Handymen and their allies manage to fight off the attack, they sustain huge losses in the process.

Gangsta Volume 5 by Kohske

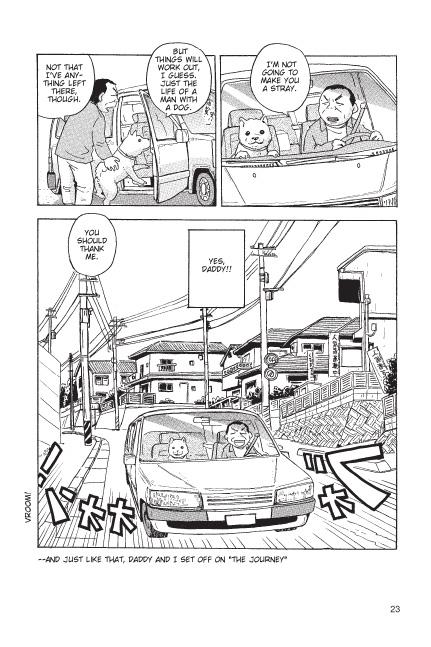

In this volume it seems clear that the mafia factions in Ergastulum are going to be headed into war. The team of Destroyers becomes more defined, and the situation for regular Twilights not affiliated with an organization is looking worse and worse. Alex has gained even more of her memories, remarking to Nic that she knew him before, only to not get a response. Worick is forced to use his sense for objects to identify corpses, and he and Nic are separated throughout most of this volume, with dangerous consequences. The Destroyers begin to tear through the city, and identify themselves as agents of the Corsica family. Still, even in the middle of a tidal wave of violence, there are quick scenes of normal daily life, when Nic hands Alex a mug as soon as she wakes up from some disturbing dreams of her past. Nic heads off to help out Loretta, and Worick is left to help fend off an attack at the Monroe family house. Things are looking fairly grim for the found family the Handymen have built for themselves. We’re starting to get more caught up with the Japanese release of Gangsta, and I know I’m going to start getting impatient as the wait between volumes grows longer.

While Gangsta does feature plenty of action and grim themes centered around drugs, class issues, and the mafia, the core story circling around Alex and her relationship with the Handymen ensures that the violence in the manga always seems to have a narrative purpose. Koshke’s narrative start small and builds up to a intercut scenes of a sprawling cast headed into some serious confrontations is building more and more suspense and tension as the series progresses. I’m also always impressed with the variety of character designs and defined looks as the manga includes more and more characters. I’m glad that Viz is continuing to give quality seinen some serious attention in the Signature Line with this title.