Word of Jiro Taniguchi’s death spread quickly this afternoon via Twitter and Facebook. It was a sobering moment for American fans; most of us imagined that he was only one great series away from mainstream recognition in the U.S., and eagerly hoped that his next release — whatever it might be — would wow new readers and make bank. Alas, the only appreciation we may see is in the value of his older, rarer titles like Icaro (a collaboration with French artist Moebius) and Samurai Legend (a collaboration with Kan Furuyama).

Manga lovers who haven’t yet discovered Taniguchi’s skill may be surprised to learn just how versatile and prolific he was. He leaves behind a rich assortment of historical dramas, hard-boiled crime thrillers, samurai swashbucklers, alpine adventures, food manga, and coming-of-age stories. As an introduction to Taniguchi’s sizeable oeuvre, I’ve compiled a list of my favorite titles, as well as a complete list of Taniguchi’s work in English.

Benkei in New York

Benkei in New York

With Jinpachi Mori • VIZ Media • 1 volume

Originally serialized in Big Comic Original, Benkei in New York focuses on a Japanese ex-pat living in New York. Like many New Yorkers, Benkei’s career is best characterized by slashes and hyphens: he’s a bartender-art forger-hitman who can paint a Millet from memory or make a killer martini. Benkei’s primary job, however, is seeking justice for murder victims’ families. Part of the series’ fun is watching him set elaborate traps for his prey, whether he’s borrowing a page from the Titus Andronicus playbook or using a grappling hook to take down a crooked longshoreman. Though we never doubt Benkei will prevail, the crackling script, imaginatively staged fight scenes, and tight plotting make Benkei in New York Taniguchi’s most satisfying crime thriller. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 3/20/12

A Distant Neighborhood

A Distant Neighborhood

Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 2 volumes

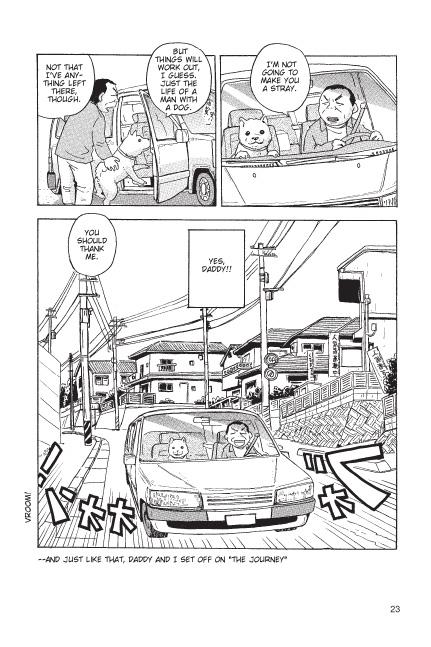

A Distant Neighborhood is a wry, wistful take on a tried-and-true premise: a salaryman is transported back in time to his high school days, and must decide whether to act on his knowledge of the past or let events unfold as they did before. We’ve seen this story many times at the multiplex — Back to the Future, Peggy Sue Got Married — but Taniguchi doesn’t play the set-up for laughs; rather, he uses Hiroshi’s predicament to underscore the challenges of family life and the awkwardness of adolescence. (Hiroshi is the same chronological age as his parents, giving him special insight into the vicissitudes of marriage, as well as the confidence to cope with teenage tribulations.) Easily one of the most emotional, most intimate stories Taniguchi’s ever told. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 2/23/11

Furari

Furari

Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 1 volume

One part Walking Man, one part Times of Botchan, this elegant collection of stories focuses on Ino Tadataka (1745-1818), the cartographer responsible for the first complete map of Japan’s coastline. We meet Tadataka shortly before he embarks on the arduous task of surveying the main island. As we follow him through the parks and streets of Edo, we realize that Tadataka is consumed with measuring; he makes mental note of every step he takes, calculating and re-calculating his routes. That’s a slender premise on which to hang a manga, but Taniguchi’s fine eye for detail transforms Tadataka’s daily walks into an immersive experience, capturing the energy, light, and sounds of the eighteenth century cityscape in all its vitality. These walks are so vividly drawn, in fact, that you could read Furari in blissful ignorance of Tadataka’s identity and still find it utterly engrossing.

Guardians of the Louvre

Guardians of the Louvre

NBM/Comics Lit • 1 VOLUME

Guardians of the Louvre has a simple premise: a Japanese artist dreams about the world’s most famous museum. In each chapter, our unnamed protagonist is temporarily transported to a particular place and time in the Louvre’s history, rubbing shoulders with famous artists, witnessing famous events, and chatting with the Nike of Samothrace, who chaperones him from exhibit to exhibit. The set-up provides Taniguchi with a nifty excuse to draw rural landscapes, gracious country manors, war-ravaged cities, and busy galleries, as well as convincing recreations of Van Gogh and Corot canvasses. If the story lacks the full emotional impact of A Zoo in Winter or A Distant Neighborhood, the gorgeous, full-color illustrations and deluxe presentation make Guardians a natural gateway for exploring Taniguchi’s work. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 1/6/17

Hotel Harbour View

Hotel Harbour View

With Natsui Sekikawa • VIZ Media • 1 volume

The two stories that comprise Hotel Harbour View are among the pulpiest in the Taniguchi canon. In the first, a man waits in a seedy Hong Kong bar for the person who’s supposed to kill him, while in the second, an assassin returns to Paris for a showdown with his former associates. Both stories can be enjoyed as simple exercises in hard-boiled crime, but attentive readers will appreciate Taniguchi and Sekikawa’s sly nods to film noir, yakuza flicks, and the French New Wave. The characters in both stories self-consciously behave like gangsters and molls, trading quips and telling well-rehearsed stories about their pasts; they even wear fedoras, a sure sign that they’re reliving their favorite moments from the silver screen. A mirrored shoot-out is the highlight of the volume, demonstrating Taniguchi’s crisp draftsmanship and mastery of perspective. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 1/14/11

Kodoku Gourmet

Kodoku Gourmet

With Masayuki Qusumi • JManga • 1 volume*

If you’re a fan of Kingyo Used Books, you may remember the chapter in which Japanese backpackers shared a dog-eared copy of Kodoku no Gourmet (a.k.a. The Lonely Gourmet) in order to feel more connected to home. Small wonder they adored Gourmet: its hero, Goro Inoshigara, is a traveler who devotes considerable time and energy to seeking out his favorite foods wherever he goes. While the manga is episodic — Goro visits a new restaurant in every chapter — Jiro Taniguchi does a wonderful job of conveying the social aspect of eating, creating brief but vivid portraits of each establishment: its clientele, its proprietors, and, of course, its signature dishes. Best of all, Taniguchi and writer Masayuki Qusumi have the good sense to limit the story to a single volume, allowing the reader to savor Goro’s culinary adventures, rather than ponder its very slight premise. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/24/12

The Summit of the Gods

The Summit of the Gods

With Yumemakura Baku • Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 5 volumes

On June 8, 1924, British explorer George Mallory started up the summit of Mt. Everest, never to be seen again. His disappearance drives the plot of The Summit of the Gods, a pulse-pounding adventure in which two modern-day climbers retrace Mallory’s steps up the Northeast Ridge, searching for clues to his fate. Although the drama ostensibly focuses on Fukumachi, a hard-charging photographer, and Habu, a tough-as-nails mountaineer, the real star of Summit is Everest. Taniguchi captures the mountain’s danger with his meticulous renderings of rock formations, glaciers, and quick-changing weather patterns, reminding us that Everest is one of the remotest places on Earth; at the top of the world, no one can hear you scream. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 10/12/2009

The Times of Botchan

The Times of Botchan

With Natsuo Sekikawa • Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 5 volumes**

In The Times of Botchan, Natsuo Sekikawa and Jiro Taniguchi immerse readers in the tumult of the Meiji Restoration. Novelist Soseki Natsume (Botchan, I Am a Cat) functions as our de facto guide, introducing us to the suffragettes, anarchists, novelists, poets, and politicians whose struggle helped create modern Japan. Taniguchi invests small details with great meaning, using them to reveal the characters’ ambivalent relationship with the West; some embrace European dress, others flatly reject it, and most, like Natsume, strike a compromise, combining a yukata with a button-down shirt and bowler hat. Though Sekikawa’s script is not as nimble as Taniguchi’s artwork, the series leaves a vivid impression nonetheless, offering modern readers a window into Natsume’s world. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/19/2010

Venice

Venice

Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 1 volume

Venice — one of the last projects Jiro Taniguchi completed before his death in 2017 — is perhaps the most beautiful work he ever produced, a paean not only to the great Italian city, but to his own superb command of light, color, and line. Rendered in watercolor and ink, Venice‘s subtle palette and expansive treatment of the page are reminiscent of Taniguchi’s Guardians of the Louvre, while its premise recalls The Walking Man, Furari, and The Solitary Gourmet, three manga in which an unnamed male character strolls through the thoroughfares and byways of a major city, stopping to admire a blossoming tree or duck into an unassuming noodle shop. Taniguchi does more than recreate the Venetian landscape, however; he conveys the rhythms and emotions of a journey as the hero retraces his grandparents’ steps through 1930s Venice. – Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 3/2/18.

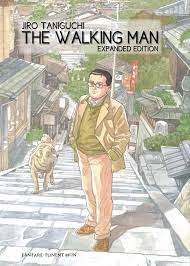

The Walking Man

The Walking Man

Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 1 volume

This nearly wordless manga follows an ordinary man through his daily routines. He walks his dog; he swims laps at the pool; he retrieves a model airplane from a tree. In less capable hands, the sheer lack of conflict would result in a dull comic, but Taniguchi invests these activities with meaning by interrupting them with moments of simple beauty: a rare bird alighting on a branch, a rooftop view of a neighborhood in spring bloom. Though we learn very little about the protagonist — he remains nameless throughout the story — his capacity for noticing and savoring these details becomes a small act of heroism, a conscious effort to resist the indifference, complacency, and impatience that blinds us to our surroundings and dulls our imaginations.

A Zoo in Winter

A Zoo in Winter

Fanfare/Ponent Mon • 1 volume

Drawing on his own experiences, Jiro Taniguchi spins an engaging tale about a young man who abandons a promising career in textile design for the opportunity to become a manga artist. Though the basic plot invites comparison with Bakuman, Taniguchi does more than just document important milestones in Hamaguchi’s career: he shows us how Hamaguchi’s emotional maturation informs every aspect of his artistry — something that’s missing from many other portrait-of-an-artist-as-a-young-man sagas, which place much greater emphasis on the pleasure of professional recognition than on the satisfaction of mastering one’s craft. Lovely, moody artwork and an appealing cast of supporting characters complete this very satisfying package. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/28/11

* * * * * *

Below is a complete list of Jiro Taniguchi’s manga in English. Please note that I’ve provided the publication information for the English translations, not the original Japanese editions. This list was last updated on August 28, 2023 to include several books that have been released since 2017.

As Artist and Author

- Taniguchi, Jiro. A Distant Neighborhood. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2009. 2 vols.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. Furari. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2017. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. Guardians of the Louvre. NBM/Comics Lit, 2016. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. The Ice Wanderer and Other Stories. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2010. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. A Journal of My Father, Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2021. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. The Quest for the Missing Girl. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2010. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. Sky Hawk. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2019. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. Venice. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2017. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. The Walking Man. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2007. 1 vol.

- Taniguchi, Jiro. A Zoo in Winter. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2011. 1 vol.

As Artist

- Boilet, Frederic and Jiro Taniguchi. Tokyo Is My Garden. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2010. 1 vol.

- Furuyama, Kan and Jiro Taniguchi. Samurai Legend. Central Park Media, 2003. 1 vol.

- Moebius and Jiro Taniguchi. Icaro. IBooks, 2003-2004. 2 vols.

- Mori, Jinpachi and Jiro Taniguchi. Benkei in New York. VIZ Media. 2001. 1 vol.

- Qusumi, Masayuki and Jiro Taniguchi. Kodoku Gourmet. JManga, 2012. 1 vol.*

- Sekikawa, Natsuo and Jiro Taniguchi. Hotel Harbour View. VIZ Media, 2001. 1 vol.

- Sekikawa, Natsuo and Jiro Taniguchi. The Times of Botchan. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2007-2010. 5 vols.**

- Yumemakura, Baku and Jiro Yaniguchi. The Summit of the Gods. Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2009-2015. 5 vols.

*This title was only released digitally through the JManga platform.

**This series is incomplete in English; the complete Japanese edition spans 10 volumes.

10. DEJA-VU: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER

10. DEJA-VU: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER 9. NARRATION OF LOVE AT 17

9. NARRATION OF LOVE AT 17 8. PRIEST

8. PRIEST 7. RUN, BONG-GU, RUN!

7. RUN, BONG-GU, RUN! 6. 10, 20, AND 30

6. 10, 20, AND 30 5. GOONG: THE ROYAL PALACE

5. GOONG: THE ROYAL PALACE 4. FOREST OF GRAY CITY

4. FOREST OF GRAY CITY 3. SHAMAN WARRIOR

3. SHAMAN WARRIOR 2. DOKEBI BRIDE

2. DOKEBI BRIDE 1. BUJA’S DIARY

1. BUJA’S DIARY