Poignant — now there’s a word I never imagined I’d be using to describe one of Junko Mizuno’s works, given her fondness for disturbing images and acid-trip plotlines. But Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is poignant, a perversely sweet and sad meditation on one small, sheep-like alien’s efforts to find his place in the universe.

Poignant — now there’s a word I never imagined I’d be using to describe one of Junko Mizuno’s works, given her fondness for disturbing images and acid-trip plotlines. But Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is poignant, a perversely sweet and sad meditation on one small, sheep-like alien’s efforts to find his place in the universe.

The story is simple: on the “cute and pink” planet of Princess Kotobuki, Pelu lives with a beautiful race of women and a “calm but carnivorous giant space hippo.” Pelu has always been aware of how different he is from his fellow Kotobukians, but when he learns that he will never be able to have a family of his own, he falls into a terrible funk, begging the hippo to eat him. When the hippo demurs — Pelu is just too woolly to be appetizing — Pelu borrows the hippo’s magic mirror and teleports to Earth in search of others like him. What Pelu discovers, however, is that Earth women view him as an exotic pet, a companion who’s entertaining but disposable. He careens from one unhappy situation to another, meeting young women who are down on their luck: an aspiring singer with a lousy voice, a homely orphan who’s raising an ungrateful brother, a pearl diver plying her trade in the sewer.

…

HAUNTED HOUSE

HAUNTED HOUSE Revisiting

Revisiting

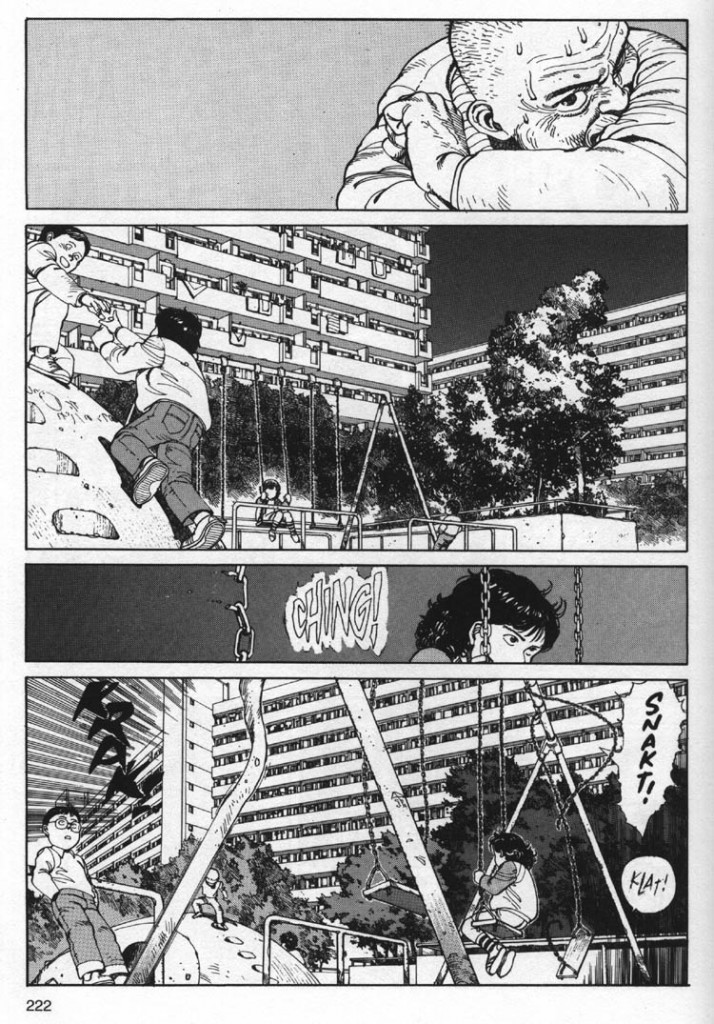

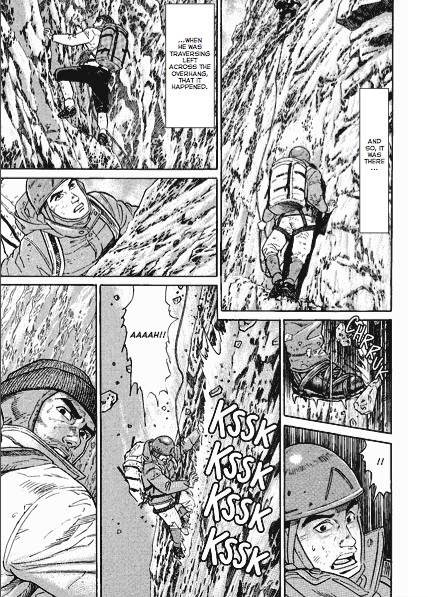

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format.

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format. I read a Rumiko Takahashi manga for the same reason I watch an Alfred Hitchcock thriller: I know exactly what I’m going to get. Certain plot elements and motifs recur throughout each artist’s work — Hitchcock loves pairing a brittle blond with a rakish cad on the run from authorities, for example, while Takahashi loves pairing a female “seer” with a demonically-tinged boy — yet the craft with which Hitchcock and Takahashi develop such tropes prevents either artist’s work from feeling stale or repetitive. Takahashi’s latest series gives ample proof that while she may have a limited repertory, she’s the undisputed master of the supernatural mystery.

I read a Rumiko Takahashi manga for the same reason I watch an Alfred Hitchcock thriller: I know exactly what I’m going to get. Certain plot elements and motifs recur throughout each artist’s work — Hitchcock loves pairing a brittle blond with a rakish cad on the run from authorities, for example, while Takahashi loves pairing a female “seer” with a demonically-tinged boy — yet the craft with which Hitchcock and Takahashi develop such tropes prevents either artist’s work from feeling stale or repetitive. Takahashi’s latest series gives ample proof that while she may have a limited repertory, she’s the undisputed master of the supernatural mystery.

Warning: the Surgeon General has determined that reading Moyasimon: Tales of Agriculture may be hazardous to your health. Individuals who routinely consume large quantities of yogurt, miso, or natto; keep stashes of Purell in their purses and desk drawers; or have an irrational fear of germs or dirt are cautioned against reading Moyasimon. Side effects include disgust, nausea, and a strong desire to wash one’s hands repeatedly. Those with stronger constitutions, however, may find this odd little comedy fun, if a little too dependent on gross-out humor for laughs.

Warning: the Surgeon General has determined that reading Moyasimon: Tales of Agriculture may be hazardous to your health. Individuals who routinely consume large quantities of yogurt, miso, or natto; keep stashes of Purell in their purses and desk drawers; or have an irrational fear of germs or dirt are cautioned against reading Moyasimon. Side effects include disgust, nausea, and a strong desire to wash one’s hands repeatedly. Those with stronger constitutions, however, may find this odd little comedy fun, if a little too dependent on gross-out humor for laughs. The humor is good-natured, though Masayuki Ishikawa indulges his inner ten-year-old’s penchant for gross-out jokes every chance he gets.He repeatedly subjects Tadayasu and Kei to Itsuki’s food fetishes, forcing them to watch Itsuki exhume and eat kiviak (a fermented seal whose belly has been stuffed with birds), or try a piece of hongohoe, a form of stingray sashimi so pungent it makes their eyes water. Ishikawa’s decision to render the bacteria as cute, roly-poly creatures with cheerful faces prevents the story from shading into horror, though it’s awfully hard to shake the image of bacteria frolicking in a bed of natto or around the slovenly Misato’s nostril.

The humor is good-natured, though Masayuki Ishikawa indulges his inner ten-year-old’s penchant for gross-out jokes every chance he gets.He repeatedly subjects Tadayasu and Kei to Itsuki’s food fetishes, forcing them to watch Itsuki exhume and eat kiviak (a fermented seal whose belly has been stuffed with birds), or try a piece of hongohoe, a form of stingray sashimi so pungent it makes their eyes water. Ishikawa’s decision to render the bacteria as cute, roly-poly creatures with cheerful faces prevents the story from shading into horror, though it’s awfully hard to shake the image of bacteria frolicking in a bed of natto or around the slovenly Misato’s nostril. 9. NIGHTMARES FOR SALE

9. NIGHTMARES FOR SALE

7. THE DEVIL WITHIN

7. THE DEVIL WITHIN 6. DRAGON SISTER!

6. DRAGON SISTER! 5. THE GORGEOUS LIFE OF STRAWBERRY-CHAN

5. THE GORGEOUS LIFE OF STRAWBERRY-CHAN 4. J-POP IDOL

4. J-POP IDOL 3. SERAPHIC FEATHER

3. SERAPHIC FEATHER 2. INNOCENT W

2. INNOCENT W 1. COLOR OF RAGE

1. COLOR OF RAGE 10. Miyuki-chan in Wonderland

10. Miyuki-chan in Wonderland 9. Nightmares for Sale

9. Nightmares for Sale 8. Arm of Kannon

8. Arm of Kannon 7. The Devil Within

7. The Devil Within 6. Dragon Sister!

6. Dragon Sister! 5. The Gorgeous Life of Strawberry-chan

5. The Gorgeous Life of Strawberry-chan 4. J-Pop Idol

4. J-Pop Idol 3. Seraphic Feather

3. Seraphic Feather 2. Innocent W

2. Innocent W 1. Color of Rage

1. Color of Rage