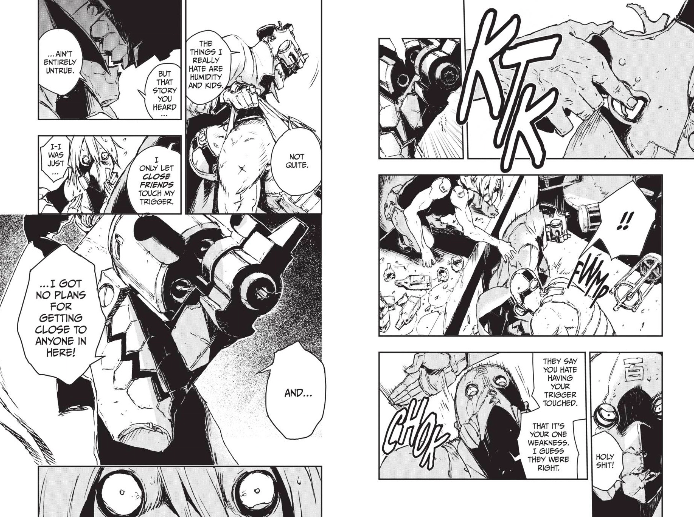

No Guns Life is a textbook example of “robo noir,” a story that borrows tropes from Double Indemnity and The Maltese Falcon and transplants them to a not-too-distant future where old and new technologies rub shoulders, and damsels in distress might, in fact, be androids. The hero is Juzo Inui, a bodyguard-for-hire who has a strong moral code and an aversion to “humidity and kids.” Like the cyborg clientele he serves, Juzo’s body has been cybernetically enhanced, his head replaced with a giant revolver. Yes—you read that right. Juzo’s head can fire a round of ammunition, a creative decision that skirts the line between funny and horrific; only Juzo’s strong moral code makes the gun-as-head concept palatable.

And speaking of that moral code, volume one focuses on Juzo’s efforts to honor a contract with a fellow cyborg. That cyborg shows up at Juzo’s office with a 12-year-old boy in tow and a request: hide the boy from the Berühen Corporation, a powerful organization that manufactures top-secret weapons. With the police and Berühen’s goons on his trail, Juzo stashes Tetsuro with his friend Mary, a back-alley surgeon, and sets out to discover why Tetsuro is such a hot commodity.

While Juzo’s exploits are entertaining, No Guns Life is a mixed bag. On the plus side, the story is briskly paced and well drawn; Tasuku Karasuma creates a strong sense of place in his establishing shots, drawing a sprawling modern city that still has hole-in-the-wall office buildings, dingy basements, and crowded tenements, all populated by characters with memorable mugs. On the minus side, the story traffics in cliches, from the beautiful assassin who carries out her duties in a skimpy costume to the villains who deliver lengthy, exposition-dense monologues before pulling the trigger. The fight scenes, too, leave something to be desired; there are too many flash-boom panels that bury the action under sound effects and speed lines, leaving the reader to guess what’s happening. None of these shortcomings are fatal, but they emphasize the fact that No Guns Life is chiefly memorable because the protagonist looks like a Second Amendment poster boy, not because the story has something new to say about the boundaries between man and machine, or the ethics of human experimentation.

The bottom line: Fans of the anime will probably enjoy No Guns Life, but readers versed in sci-fi and noir conventions may find it too pedestrian to make a lasting impression.

A review copy was provided by VIZ Media, LLC. Volume one will be released on September 17, 2019. Read a free preview here.

NO GUNS LIFE, VOL. 1 • STORY AND ART BY TASUKU KARASUMA • TRANSLATED BY JOE YAMAZAKI • VIZ MEDIA • RATED T+, FOR OLDER TEENS (VIOLENCE, SCANTILY CLAD WOMEN) • 248 pp.