I’m pleased to report that 2009 yielded fewer jaw-droppingly bad manga in the vein of Eiken, J-Pop Idol, or Shiki Tsukai — surely the most confusing manga ever written about weather — though it wasn’t devoid of clunkers. Below are my top five nominees for Worst Manga of 2009. Some earned demerits for lousy art or writing; others for gross sexism; and others for insulting my intelligence as a reader. Keep in mind that while I try to read widely, there are definitely titles I’ve missed or avoided — Tantric Stripfighter Trina, anyone? — so I encourage you to share you own nominees for The Manga Hall of Shame, as well as your reactions to this year’s dishonorees.

…

5. Pig Bride

5. Pig Bride  4. Zone-00

4. Zone-00  3. Black Bird

3. Black Bird 2. Lucky Star

2. Lucky Star 1. Maria Holic

1. Maria Holic 10. Oishinbo a la Carte

10. Oishinbo a la Carte

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

I mean no disrespect to Tetsu Kariya or Akira Hanasaki when I say that the Vegetables volume of Oishinbo A la Carte irresistibly reminded me of 1970s television. Back in the day when there were only three networks, hour-long dramas doggedly followed the same formula: they dramatized a problem — say, drinking and driving, or falling in with a bad crowd — then resolved it with a little action and a lot of talking, culminating in a freeze-frame shot of the entire cast laughing at corny situational humor. Oishinbo follows this template to a tee, using hot-button issues such as bullying and pollution to preach the healing power of vegetables. The stories are as hokey and predictable as an episode of CHiPs or Little House on the Prairie, but entertaining in their sincerity.

I mean no disrespect to Tetsu Kariya or Akira Hanasaki when I say that the Vegetables volume of Oishinbo A la Carte irresistibly reminded me of 1970s television. Back in the day when there were only three networks, hour-long dramas doggedly followed the same formula: they dramatized a problem — say, drinking and driving, or falling in with a bad crowd — then resolved it with a little action and a lot of talking, culminating in a freeze-frame shot of the entire cast laughing at corny situational humor. Oishinbo follows this template to a tee, using hot-button issues such as bullying and pollution to preach the healing power of vegetables. The stories are as hokey and predictable as an episode of CHiPs or Little House on the Prairie, but entertaining in their sincerity. Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki.

Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki. Poignant — now there’s a word I never imagined I’d be using to describe one of Junko Mizuno’s works, given her fondness for disturbing images and acid-trip plotlines. But Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is poignant, a perversely sweet and sad meditation on one small, sheep-like alien’s efforts to find his place in the universe.

Poignant — now there’s a word I never imagined I’d be using to describe one of Junko Mizuno’s works, given her fondness for disturbing images and acid-trip plotlines. But Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is poignant, a perversely sweet and sad meditation on one small, sheep-like alien’s efforts to find his place in the universe. HAUNTED HOUSE

HAUNTED HOUSE Revisiting

Revisiting

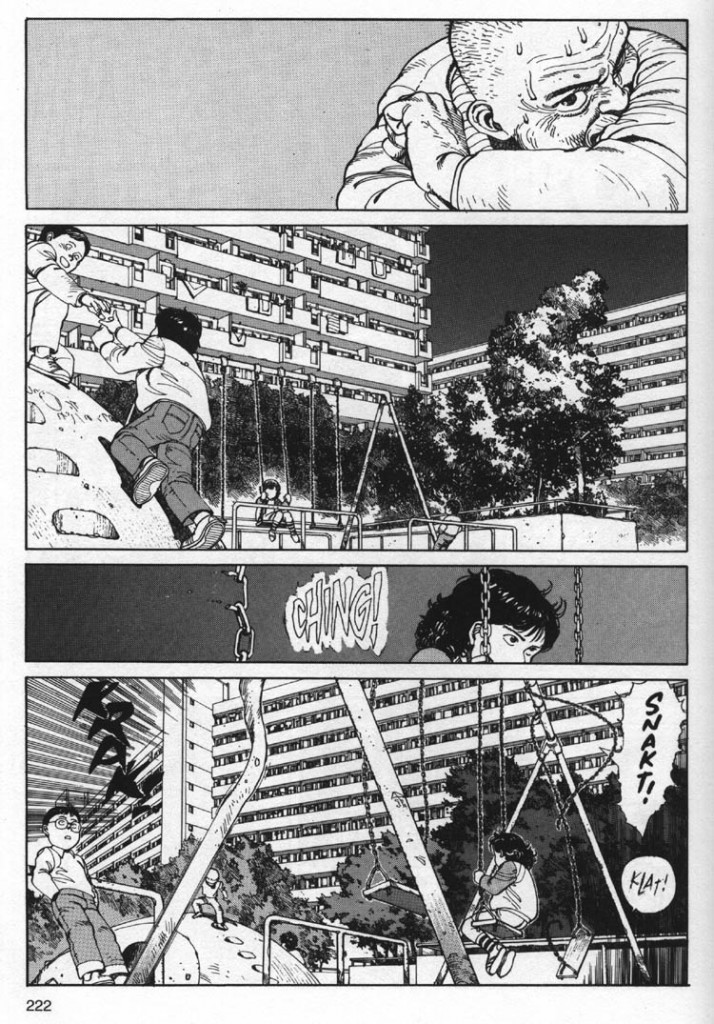

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format.

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format.