After the main Love*Com story finished, mangaka Aya Nakahara published a few additional bonus stories, which are collected in the series’ seventeenth and final volume. Three stories depict Ôtani and Risa during their junior high years and one revisits the gang four months after graduation. One of the major flaws of Love*Com in its later volumes was that, in a transparent effort to milk the series for all it was worth, the focus drifted too much from the leads to the uninspiring supporting cast. Here, at least, each story features one or both of the protagonists in the starring role(s).

After the main Love*Com story finished, mangaka Aya Nakahara published a few additional bonus stories, which are collected in the series’ seventeenth and final volume. Three stories depict Ôtani and Risa during their junior high years and one revisits the gang four months after graduation. One of the major flaws of Love*Com in its later volumes was that, in a transparent effort to milk the series for all it was worth, the focus drifted too much from the leads to the uninspiring supporting cast. Here, at least, each story features one or both of the protagonists in the starring role(s).

Despite its hokey setup—practically every semi-significant character from the series coincidentally converges on the same beach on the same day—the post-graduation story is not only the best of the four, but also provides the best Risa/Ôtani scene in quite some time. It deals with Risa’s feelings of being left behind by her undergraduate friends, who are off having new experiences with people she doesn’t know while she contends with the challenges of fashion stylist school, which is not going as well as she had hoped. Somehow, this series works best when Risa is miserable, and when Ôtani steps up to the plate to cheer her up and listen to her troubles, it provides a better and more personal farewell for the series than the full-cast send-off volume sixteen offered.

It’s been a long time since I paused to admire and reread a particularly sweet moment between these two characters, and I can’t help feeling grateful that I was able to experience it one more time before the end. Maybe, just a little, Love*Com has redeemed itself.

Review copy provided by the publisher. Review originally published at Manga Recon.

First published in 1964, Harriet the Spy featured a radically different kind of heroine than the sweet, obedient girls found in most mid-century juvenile lit; Harriet was bossy, self-centered, and confident, with a flair for self-dramatization and a foul mouth. She favored fake glasses, blue jeans, and a “spy tool” belt over angora sweaters or skirts, and she roamed the streets of Manhattan doing the kind of reckless, bold things that were supposed to be off-limits to girls: peering through skylights, hiding in alleys, concealing herself in dumbwaiters, filling her notebooks with scathing observations about classmates and neighbors. Perhaps the most original aspect of Louise Fitzhugh’s character was Harriet’s complete and utter commitment to the idea of being a writer; unlike Nancy Drew, Harriet wasn’t a goody-goody sleuth who wanted to help others, but a ruthless observer of human folly who viewed spying as necessary preparation for becoming an author.

First published in 1964, Harriet the Spy featured a radically different kind of heroine than the sweet, obedient girls found in most mid-century juvenile lit; Harriet was bossy, self-centered, and confident, with a flair for self-dramatization and a foul mouth. She favored fake glasses, blue jeans, and a “spy tool” belt over angora sweaters or skirts, and she roamed the streets of Manhattan doing the kind of reckless, bold things that were supposed to be off-limits to girls: peering through skylights, hiding in alleys, concealing herself in dumbwaiters, filling her notebooks with scathing observations about classmates and neighbors. Perhaps the most original aspect of Louise Fitzhugh’s character was Harriet’s complete and utter commitment to the idea of being a writer; unlike Nancy Drew, Harriet wasn’t a goody-goody sleuth who wanted to help others, but a ruthless observer of human folly who viewed spying as necessary preparation for becoming an author. Nico Hayashi, code name “Sexy Voice,” is a bit older than Harriet — Nico is 14, Harriet is 11 — but she’s cut from the same bolt of cloth, as Sexy Voice and Robo amply demonstrates. Like Harriet, Nico entertains fanciful ambitions: “I want to be a spy when I grow up, or maybe a fortune teller,” she informs her soon-to-be-employer. “Either way, I’m in training. A pro has to hone her skills.” Nico, too, has a spy outfit — in her case, comprised of a wig and falsies — and an assortment of “spy tools” that include her cell phone and a stamp that allows her to forge her parents’ signature on notes excusing her from school. Like Harriet, Nico hungers for the kind of adventure that’s supposed to be off-limits to girls, skipping school to pursue leads, analyzing a kidnapper’s ransom call, luring bad guys into traps. Most importantly, both girls are students of adult behavior. Both Harriet the Spy and Sexy Voice and Robo include a scene in which the heroine constructs detailed character profiles from a few snippets of conversation. The similarities between these moments are striking. In Fitzhugh’s book, Harriet visits a neighborhood diner, nursing an egg cream while listening to other customers’ conversations:

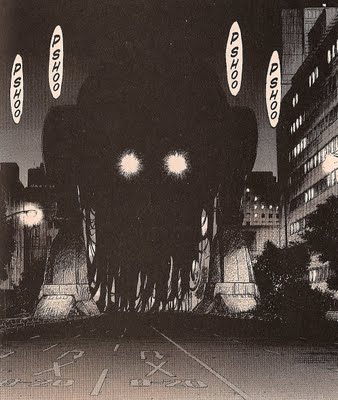

Nico Hayashi, code name “Sexy Voice,” is a bit older than Harriet — Nico is 14, Harriet is 11 — but she’s cut from the same bolt of cloth, as Sexy Voice and Robo amply demonstrates. Like Harriet, Nico entertains fanciful ambitions: “I want to be a spy when I grow up, or maybe a fortune teller,” she informs her soon-to-be-employer. “Either way, I’m in training. A pro has to hone her skills.” Nico, too, has a spy outfit — in her case, comprised of a wig and falsies — and an assortment of “spy tools” that include her cell phone and a stamp that allows her to forge her parents’ signature on notes excusing her from school. Like Harriet, Nico hungers for the kind of adventure that’s supposed to be off-limits to girls, skipping school to pursue leads, analyzing a kidnapper’s ransom call, luring bad guys into traps. Most importantly, both girls are students of adult behavior. Both Harriet the Spy and Sexy Voice and Robo include a scene in which the heroine constructs detailed character profiles from a few snippets of conversation. The similarities between these moments are striking. In Fitzhugh’s book, Harriet visits a neighborhood diner, nursing an egg cream while listening to other customers’ conversations: From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

5. Pig Bride

5. Pig Bride  4. Zone-00

4. Zone-00  3. Black Bird

3. Black Bird 2. Lucky Star

2. Lucky Star 1. Maria Holic

1. Maria Holic

10. Oishinbo a la Carte

10. Oishinbo a la Carte

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka