We’re in the middle of a sports-manga renaissance in the US, with publishers offering an unprecedented range of titles from Kurokuro’s Basketball and Haikyu!! to Yowamushi Pedal and Welcome to the Ballroom. Leading the pack is Kodansha Comics, which is making an astonishing range of titles available through their digital-only and digital-first initiatives. And astonishing it is: alongside obvious choices like the baseball-centric Ace of the Diamond, you’ll also find soccer manga (Days, Giant Killing, Sayanora, Football), rugby manga (All Out!!), mixed-martial arts manga (All-Rounder Meguru), and card game manga (Chihayafuru). Kodansha’s latest acquisition is Shojo FIGHT!, a volleyball series that reads like Dynasty with knee pads.

I mean that as a compliment.

The first chapter briskly introduces us to the three principle members of the Hakuumzan Private Academy Middle School volleyball team: Neri, a talented but difficult personality who has trouble playing well with others (literally and figuratively); Koyuki, a telegenic setter who moonlights on the Junior National team; and Chiyo, a jealous teammate who slots into the Joan Collins role of Queen Bitch. As we learn in the opening pages, Neri’s temper frequently relegates her to the bench, even though her teammates firmly believe that she’s in a league of her own as both a setter and a hitter — a point that Chiyo lords over the emotionally vulnerable Koyuki. Koyuki, for her part, feels isolated from her teammates who say nice things to her face but trash her playing when she’s not around. Though Chiyo bluntly dismisses Neri as “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” Koyuki makes a concerted effort to befriend Neri, whom she views as a peer on the court.

The dynamic between these three players would be enough for an entire series, but Yoko Nihonbashi surrounds them with a boisterous cast of supporting characters who run the gamut from Odagiri, a shy Neri fangirl, to the Shikisama brothers, two gifted volleyball players who are, of course, handsome, sharp-witted, and fiercely loyal to their childhood friend… well, I’ll let you figure out that particular triangle on your own, though it’s not hard to guess who she is. While these figures are sketched more hastily than the principle trio, Nihonbashi offers tantalizing clues about how they will figure into the conflict between Neri and her teammates.

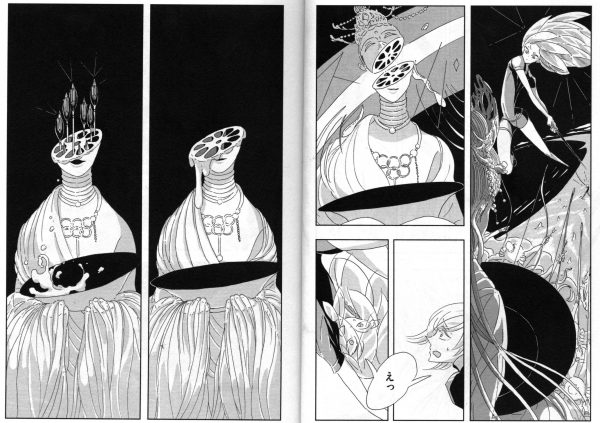

What will make or break this series for most readers is the art. As numerous folks have observed, Nihonbashi’s thick lines, wide-eyed characters, and computer-generated fills more closely conform to Americans’ perception of what OEL manga looks like — think Peach Fuzz or Van Von Hunter — than a licensed seinen or shojo title. I think that’s a valid observation, though it’s worth noting that Nihonbashi is a Japanese artist writing for Evening magazine, not a Tokyopop Rising Star of Manga. The boldness of Nihonbashi’s linework, and her dense but well structured layouts, aren’t the least bit amateurish or unpolished. If anything, they demonstrate a good understanding of game mechanics and a flair for drawing expressive, animated faces that telegraph the characters’ emotional states; the malicious twinkle in Chiyo’s eye speaks more loudly than her poisonous words — and that’s saying something.

My suggestion: try before you buy! The first 50 pages of Shojo FIGHT! can be viewed for free at the Kodansha Comics website. There’s enough drama packed into that opening chapter to hook any soap opera fan or sports enthusiast, and if the sudsy plotting isn’t enough to pique your interest, Neri will be: she’s prickly and complicated but appealing, not least because she seems like a real teenage athlete struggling to reconcile her desire to dominate the court with her desire to be part of the team.

The entire first volume goes on sale today (September 26th) via Amazon, B&N, ComiXology, and other digital book platforms.