Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest.

Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest.

The story starts from an old-as-the-hills premise: the orphan who grows up to marry — or, in this case, pine for — her guardian. In The Name of the Flower, the orphan role is fulfilled by Chouko, who, at the age of sixteen, lost her parents in a car accident. Overwhelmed by grief, Chouko stopped speaking or showing emotion until a distant relative took her into his home, admonished her for being silent, and suggested that she revive the house’s lifeless garden. Flash forward two years, and Chouko has emerged from her shell, still quiet but full of calm purpose and warm feelings for Kei, her guardian. Kei, however, is a troubled soul, a successful novelist who achieved notoriety for a string of nihilistic books written while he was in his early twenties. His eccentric garb (he wears a yukata just about everywhere) and brusque demeanor suggest a man in full flight from the outside world — or at least some painful memories.

…

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12 4. X-Day

4. X-Day 3. A.I. Revolution

3. A.I. Revolution 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. Love Song

1. Love Song Duck Prince

Duck Prince Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.) In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”

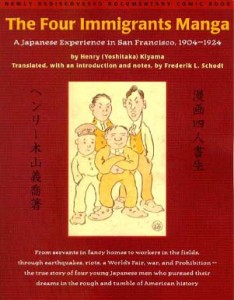

In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.” THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924 The Four Immigrants Manga

The Four Immigrants Manga Parasyte

Parasyte Satsuma Gishiden

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima.

About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima. PINEAPPLE ARMY

PINEAPPLE ARMY The characters in Solanin are suffering from what I call a “pre-life crisis”—that moment in your twenties when you realize that it’s time to join the world of adult responsibility, but you aren’t quite ready to abandon dreams of indie-rock stardom, literary genius, or artistic greatness. From a dramatic standpoint, the pre-life crisis doesn’t make the best material for a novel, graphic or otherwise, as twenty-something angst can seem trivial when compared with the vicissitudes of middle and old age. Yet Asano Inio almost pulls it off on the strength of his appealing characters and astute observations.

The characters in Solanin are suffering from what I call a “pre-life crisis”—that moment in your twenties when you realize that it’s time to join the world of adult responsibility, but you aren’t quite ready to abandon dreams of indie-rock stardom, literary genius, or artistic greatness. From a dramatic standpoint, the pre-life crisis doesn’t make the best material for a novel, graphic or otherwise, as twenty-something angst can seem trivial when compared with the vicissitudes of middle and old age. Yet Asano Inio almost pulls it off on the strength of his appealing characters and astute observations.

Come for the cat, stay for the cartooning — that’s how I’d summarize the appeal of Chi’s Sweet Home, a deceptively simple story about a family that adopts a wayward kitten. Chi certainly works as an all-ages comic, as the clean, simple layouts do a good job of telling the story, even without the addition of dialogue or voice-overs. But Chi is more than just cute kitty antics; it’s a thoughtful reflection on the joys and difficulties of pet ownership, one that invites readers of all ages to see the world through their cat or dog’s eyes and imagine how an animal adapts to life among humans.

Come for the cat, stay for the cartooning — that’s how I’d summarize the appeal of Chi’s Sweet Home, a deceptively simple story about a family that adopts a wayward kitten. Chi certainly works as an all-ages comic, as the clean, simple layouts do a good job of telling the story, even without the addition of dialogue or voice-overs. But Chi is more than just cute kitty antics; it’s a thoughtful reflection on the joys and difficulties of pet ownership, one that invites readers of all ages to see the world through their cat or dog’s eyes and imagine how an animal adapts to life among humans.