In his essay Moe: The Cult of the Child, Jason Thompson argues that one of the most pernicious aspects of moe is the way in which the father-daughter relationship is sentimentalized. “Moe is a fantasy of girlhood seen through chauvinistic male eyes,” he explains, “in which adorable girls do adorable things while living in questionable situations with adult men.” The idealized “daughters” found in Kanna, Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase, and Yotsuba&! adore their “fathers” in an uncritical fashion, showering them with affection and trying — often unsuccessfully — to play the role of wife and mother, in the process endearing themselves to both the hero and the reader with their burnt meals, singed shirts, and sincere desire to please.

Blood Alone provides an instructive example of this phenomenon. The story focuses on Misaki, a young female vampire whose appearance and mental age peg her as an eleven- or twelve-year-old girl. Misaki lives with Kuroe, a twenty-something man who’s been appointed as her guardian — though in Yotsuba-eqsue fashion, the circumstances surrounding their arrangement remain hazy in the early volumes of the manga. When we first meet Kuroe, he seems as easygoing as Yotsuba’s “dad,” a genial, slightly bumbling man who supports himself by writing novels and moonlighting as a private detective. And if that isn’t awww-inducing enough, Kuroe’s first gig is to locate a missing pet, a job that Misaki takes upon herself to complete when Kuroe bumps up against a publisher’s deadline.

As soon as Misaki’s cat-hunting mission goes awry, however, we see another side of Kuroe: he’s handy with his fists, quickly dispatching a rogue vampire who threatens Misaki’s safety. Small wonder, then, that Misaki has a crush on her guardian; not only is he the kind of sensitive guy who writes books and rescues kitties, he’s also the kind of guy who goes to extreme lengths to protect his family.

If that were the extent of their relationship, Blood Alone would provide enough heart-tugging moments to appeal to moe enthusiasts without offending other readers’ sensibilities, but Masayuki Takano plays up the romantic angle to an uncomfortable degree. The most unsettling gambit, by far, is Kuroe and Misaki’s penchant for sleeping in the same bed together. That a grown man would even entertain such behavior is disturbing enough, but what makes it particularly egregious is that Kuroe rationalizes this arrangement because Misaki is afraid of “ghosts and monsters.” I think we’re supposed to find this endearing — a vampire who’s afraid of the dark! — but it serves to infantilize Misaki even more than her little-girl dresses, terrible cooking, and fierce jealousy of Sainome, the one adult woman in Kuroe’s life. If we only saw things from Misaki’s point of view, one could make a solid argument that Masayuki Takanao is deliberately showing us things through a distorted lens, but Takano’s narrative technique simply isn’t that sophisticated; Kuroe’s behavior — his solicitousness, his guilt — suggests that Misaki’s understanding of their relationship isn’t as far off the mark as an adult reader might hope.

This kind of confusion extends to other aspects of the manga as well. About one-third of the stories fall into the category of supernatural suspense. The dialogue favors information dump over organic revelation of fact, while the plot frequently hinges on characters suddenly disclosing a convenient power or revealing their vampire connections. Yet these chapters are more effective than the slice-of-life scenes, blending elements of urban fantasy, police procedural, and Gothic horror into atmospheric stories about vampires who use the anonymity of cities to hide among — and prey on — the living.

The rest of the series, however, is jarringly at odds with the suspenseful mood of these stories; we’re treated to numerous chapters in which very little happens, save a Valentine’s Day exchange of chocolates or a jealous spat. As a result, the series feels aimless; whatever overarching storyline may bind the supernatural element to the domestic is too deeply buried to give the series a sense of narrative urgency.

Art-wise, Blood Alone boasts attractive, cleanly executed character designs and settings, but stiff, unpersuasive action scenes. Backgrounds disappear when fists fly, and the bodies look like awkwardly posed mannequins, their legs and arms held away from the torso at unnatural angles.

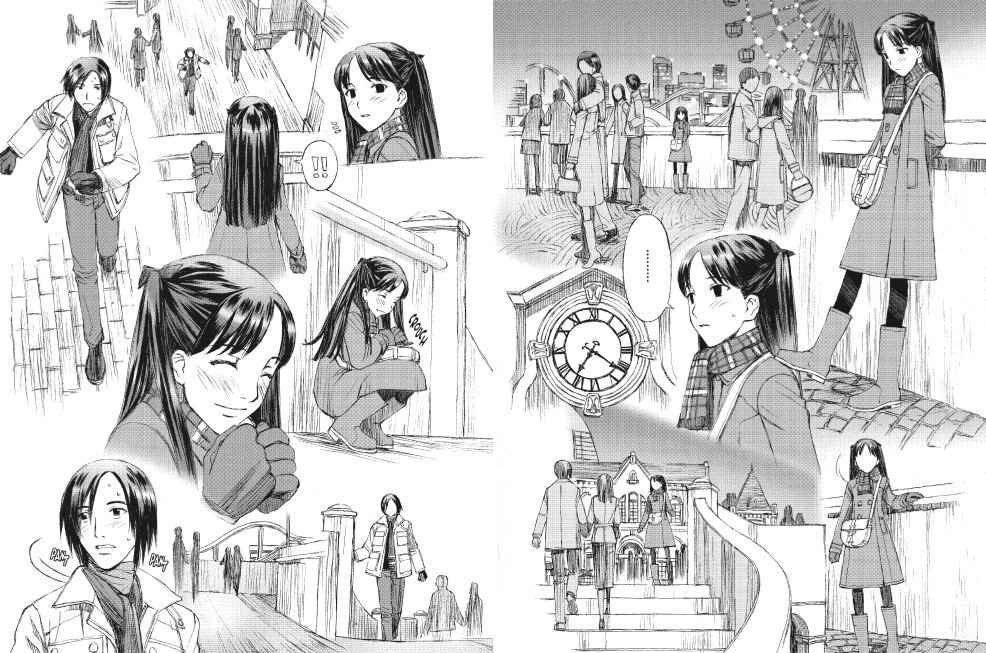

The most distinctive element of the artwork is Takano’s willingness to abandon grids altogether, creating fluid, full-page sequences in which the characters’ faces play a similar role to panel boundaries and shapes in directing the eye across the page. In this spread, for example, Sainome gently teases Misaki about her relationship with Kuroe:

The undulating lines and overlapping images give these pages a pleasing, sensual quality, but what’s most striking is the way in which the strongest lines on the page point to Misaki’s eyes and mouth, showing us how difficult it is for Misaki to conceal her feelings for Kuroe. The wordless sequence below — in which Misaki waits for Kuroe to join her on a date — works in a similar fashion, using the direction of Misaki’s gaze to lead us through the proper sequence of events:

Though these two scenes are gracefully executed, they point to the biggest problem with Blood Alone: Misaki and Kuroe aren’t portrayed as ward and guardian, or brother and sister, but as star-crossed lovers whose age and circumstance make it impossible for them to fully express their true feelings for one another. Some readers may find their unconsummated romance heartwarming, the story of a love that can never be, but for other readers, Misaki and Kuroe’s relationship will be a deal-breaker, a sentimental and uncritical portrayal of an inappropriate relationship between a young vampire and her adult protector.

Review copy provided by Seven Seas.

BLOOD ALONE, VOLS. 1-3 • BY MASAYUKI TAKANO • SEVEN SEAS • 600 pp. • RATING: TEEN (13+)

MJ: Okay! First of all, I took a look at volume three of Shunju Aono’s

MJ: Okay! First of all, I took a look at volume three of Shunju Aono’s  MICHELLE: Both of my choices tonight are from VIZ, one each from the Shonen Jump and Shojo Beat imprints. From the former, I read the first two volumes of

MICHELLE: Both of my choices tonight are from VIZ, one each from the Shonen Jump and Shojo Beat imprints. From the former, I read the first two volumes of  MJ: New England is rarely balmy in May, though the weather has been good for hiking. My heart is plenty balmy, though, after checking in with a long-running favorite, Park SoHee’s

MJ: New England is rarely balmy in May, though the weather has been good for hiking. My heart is plenty balmy, though, after checking in with a long-running favorite, Park SoHee’s  MICHELLE: My second read was the third volume of the ever-charming The Story of Saiunkoku. Technically, this would probably be classified under the genre of historical fantasy, but really, it reads somewhat like a slice-of-life tale. Shurei Hong, once consort and tutor to the emperor, Ryuki, has returned home after successfully inspiring him to govern properly. Most of the money she earned for doing so has already been spent, however, and the upcoming summer storms will necessitate more repairs to the family home. The family’s financial situation inspires their servant, Seiran, to accept a job dealing with bandits and when Shurei is herself offered the chance to help out in the understaffed Ministry of the Treasury, she accepts.

MICHELLE: My second read was the third volume of the ever-charming The Story of Saiunkoku. Technically, this would probably be classified under the genre of historical fantasy, but really, it reads somewhat like a slice-of-life tale. Shurei Hong, once consort and tutor to the emperor, Ryuki, has returned home after successfully inspiring him to govern properly. Most of the money she earned for doing so has already been spent, however, and the upcoming summer storms will necessitate more repairs to the family home. The family’s financial situation inspires their servant, Seiran, to accept a job dealing with bandits and when Shurei is herself offered the chance to help out in the understaffed Ministry of the Treasury, she accepts.

May 5th is a huge day for Hikaru no Go fans. Not only is the date extremely important in the storyline of the series itself, but the Japanese words for “5” and “Go” are identical. In fact, after he starts getting into the game of Go, the protagonist, Hikaru, is depicted wearing a t-shirt that reads, “Let’s 5!” instead of “Let’s go!”

May 5th is a huge day for Hikaru no Go fans. Not only is the date extremely important in the storyline of the series itself, but the Japanese words for “5” and “Go” are identical. In fact, after he starts getting into the game of Go, the protagonist, Hikaru, is depicted wearing a t-shirt that reads, “Let’s 5!” instead of “Let’s go!”