When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century.

When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century.

Yumi Hayakawa, the series’ plucky heroine, is blissfully unaware of Kaen’s existence when she and her beloved pet Kansuke enroll at Matabi Academy. Within hours of their arrival, however, they find themselves face-to-face with a blood-thirsty demon who describes himself as “the right knee” of Kaen. (N.B. He’s a lot more badass than “right knee” might suggest, and has a coat of human skulls to prove it.) The ensuing battle reveals that the school’s six-member student council is, in fact, comprised of magically-enhanced warriors who fight in concert with their pets. Each Guardian has a different ability; some possess super-strength, while others transform their cats into powerful weapons. Though prophecy foretold only six “fighting pairs,” Yumi and Kansuke quickly discover that they, too, have similar powers that obligate them to fight alongside the Guardians. Iwahara hasn’t explained why the prophecy proved wrong — a cloudy crystal ball, perhaps? — but it’s a safe bet that Yumi and Kansuke will have a special role to play in the impending showdown with Kaen, who has yet to materialize.

…

Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

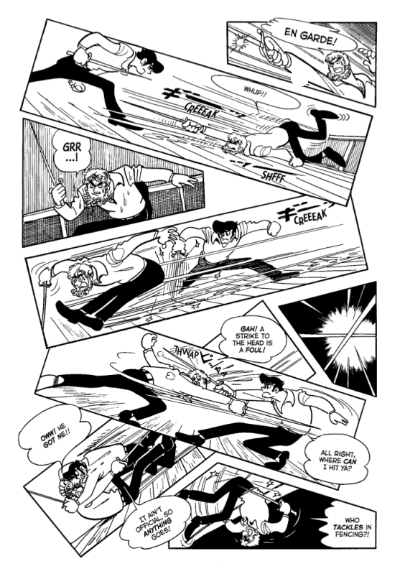

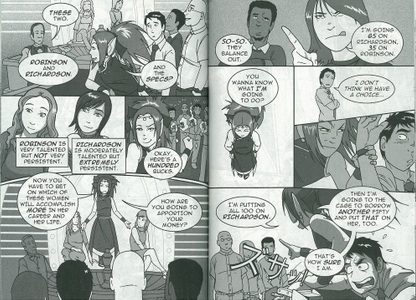

Dangerous Minds, Dead Poets Society, Stand and Deliver, and To Sir, With Love all depict teachers who are heroic in their self-sacrifice, renouncing money, family ties, and even their reputations in order to inspire students. Kojiro Ishido, the anti-hero of Bamboo Blade, won’t be mistaken for any of these noble educators. He’s bankrupt, morally and financially, and so eager to dig himself out of debt that he’d exploit his students in a heartbeat.

Dangerous Minds, Dead Poets Society, Stand and Deliver, and To Sir, With Love all depict teachers who are heroic in their self-sacrifice, renouncing money, family ties, and even their reputations in order to inspire students. Kojiro Ishido, the anti-hero of Bamboo Blade, won’t be mistaken for any of these noble educators. He’s bankrupt, morally and financially, and so eager to dig himself out of debt that he’d exploit his students in a heartbeat.

Though its name evokes images of the White House — and maybe even the unctuous Josiah Bartlett — The History of the West Wing is, in fact, an adaptation of a twelfth-century play by the Moliere of China, Wang Shifu.

Though its name evokes images of the White House — and maybe even the unctuous Josiah Bartlett — The History of the West Wing is, in fact, an adaptation of a twelfth-century play by the Moliere of China, Wang Shifu.

The year is 1955. Twenty-year-old Masayo, an aspiring painter from Hakodate, apprentices herself to Goro Kawabuko, a handsome widower who teaches at a Tokyo art college. In exchange for a weekly lesson, Masayo agrees to keep house for Goro and tutor his daughter Momoko, a strange, withdrawn child whose only companion is a regal white cat named Lala.

The year is 1955. Twenty-year-old Masayo, an aspiring painter from Hakodate, apprentices herself to Goro Kawabuko, a handsome widower who teaches at a Tokyo art college. In exchange for a weekly lesson, Masayo agrees to keep house for Goro and tutor his daughter Momoko, a strange, withdrawn child whose only companion is a regal white cat named Lala. Given the current economic climate, any book with the subtitle The Last Career Guide You’ll Ever Need sounds like a worthwhile investment. Job seekers should be warned, however, that The Adventures of Johnny Bunko isn’t about crafting the perfect resume, networking, or nailing the interview, but finding a career path that suits your strengths and personal values. Readers should also note that Johnny Bunko’s format defies easy categorization, straddling the fence between graphic novel and self-help book. Some readers may find Johnny Bunko’s mixture of slapstick humor and advice charming, while others may find the presentation too gimmicky for their tastes.

Given the current economic climate, any book with the subtitle The Last Career Guide You’ll Ever Need sounds like a worthwhile investment. Job seekers should be warned, however, that The Adventures of Johnny Bunko isn’t about crafting the perfect resume, networking, or nailing the interview, but finding a career path that suits your strengths and personal values. Readers should also note that Johnny Bunko’s format defies easy categorization, straddling the fence between graphic novel and self-help book. Some readers may find Johnny Bunko’s mixture of slapstick humor and advice charming, while others may find the presentation too gimmicky for their tastes.

Night of the Beasts may not be Chika Shiomi’s best work, but it’s certainly her most ambitious, a sweeping horror-fantasy with detailed artwork and nakedly emotional dialogue reminiscent of CLAMP’s Tokyo Babylon and X/1999 .

Night of the Beasts may not be Chika Shiomi’s best work, but it’s certainly her most ambitious, a sweeping horror-fantasy with detailed artwork and nakedly emotional dialogue reminiscent of CLAMP’s Tokyo Babylon and X/1999 . The eponymous heroine of Canon is a smart, tough-talking vigilante who’s saving the world, one vampire at a time. For most of her life, Canon was a sickly but otherwise unremarkable human — that is, until a nosferatu decided to make Lunchables™ of her high school class. Canon, the sole survivor of the attack, was transformed into a vampire whose blood has an amazing property: it can restore other victims to their former human selves. She’s determined to rescue as many human-vampire converts as she can, prowling the streets of Tokyo in search of others like her. She’s also resolved to find and kill Rod, the handsome blonde vampire whom she believes murdered her friends. Joining her are two vampires with agendas of their own: Fuui, a talking crow who’s always scavenging for blood, and Sakaki, a half-vamp who harbors an even deeper grudge against Rod for killing his family.

The eponymous heroine of Canon is a smart, tough-talking vigilante who’s saving the world, one vampire at a time. For most of her life, Canon was a sickly but otherwise unremarkable human — that is, until a nosferatu decided to make Lunchables™ of her high school class. Canon, the sole survivor of the attack, was transformed into a vampire whose blood has an amazing property: it can restore other victims to their former human selves. She’s determined to rescue as many human-vampire converts as she can, prowling the streets of Tokyo in search of others like her. She’s also resolved to find and kill Rod, the handsome blonde vampire whom she believes murdered her friends. Joining her are two vampires with agendas of their own: Fuui, a talking crow who’s always scavenging for blood, and Sakaki, a half-vamp who harbors an even deeper grudge against Rod for killing his family.