Whether by accident or design, the very first manga I read and liked were horror titles: “The Laughing Target,” Mermaid Saga, Uzumaki. I’m not sure why I find spooky stories so compelling in manga form; I don’t generally read horror novels, and I don’t have the constitution for gory movies. But manga about zombies? Or vampires? Or angry spirits seeking to avenge their own deaths? Well, there’s always room on my bookshelf for another one, even if the stories sometimes feel overly familiar or — in the case of artists like Kanako Inuki and Kazuo Umezu — make no sense at all. Below is a list of my ten favorite scary manga, which run the gamut from psychological horror to straight-up ick.

10. Lament of the Lamb

10. Lament of the Lamb

By Kei Toume • Tokyopop • 7 volumes

Kei Toume puts a novel spin on vampirism, presenting it not as a supernatural phenomenon, but as a symptom of a rare genetic disorder. His brother-and-sister protagonists, Kazuna and Chizuna, begin exhibiting the same tendencies as their deceased mother, losing control at the sight or suggestion of blood, and enduring cravings so intense they induce temporary insanity. Long on atmosphere and short on plot, Lament of the Lamb won’t be every vampire lover’s idea of a rip-snortin’ read; the manga focuses primarily on the intense, unhealthy relationship between Kazuna and Chizuna, and very little on blood-sucking. What makes Lament of the Lamb so deeply unsettling, however, is the strong current of violence and fear that flows just beneath its surface; Kazuna and Chizuna may not be predators, but we see just how much self-control it takes for them to contain their bloodlust.

9. School Zone

9. School Zone

By Kanako Inuki • Dark Horse • 3 volumes

In this odd, hallucinatory, and sometimes very funny series, a group of students summon the ghosts of people who died on school grounds, unleashing the spirits’ wrath on their unsuspecting classmates. School Zone is as much a meditation on childhood fears of being ridiculed or ostracized as it is a traditional ghost story; time and again, the students’ own response to the ghosts is often more horrific than the ghosts’ behavior. Inuki’s artwork isn’t as gory or imaginative as some of her peers’, though she demonstrates a genuine flair for comically gruesome thrills: one girl is dragged into a toilet, for example, while another is attacked by a scaly, long-armed creature that lives in the infirmary. Where Inuki really shines, however, is in her ability to capture the primal terror that a dark, empty building can inspire in the most rational person. Even when the story takes one its many silly detours — and yes, there are many WTF?! moments in School Zone — Inuki makes us feel her characters’ vulnerability as they explore the school grounds after hours. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 10/29/09

8. Mail

8. Mail

By Housui Yamazaki • Dark Horse • 3 volumes

If you like you horror neat with a twist, Mail might be your kind of manga: a meticulously crafted selection of short, spooky tales in which a handsome exorcist goes toe-to-toe with all sort of ghosts. The stories are a mixture of urban legend and folklore: a GPS system which directs a woman to the scene of a crime, an accident victim who haunts the elevator shaft where he died, a possessed doll. Through precise linework and superb command of light, Hosui Yamakazi transforms everyday situations — returning home from work, logging onto a computer — into extraordinary ones in which shadows and corners harbor very nasty surprises. Best of all, Mail never overstays its welcome; it’s the manga equivalent of the Goldberg Variations, offering a number of short, trenchant variations on a single theme and then wrapping things up neatly.

7. After School Nightmare

7. After School Nightmare

By Setona Mizushiro • Go! Comi • 10 volumes

Masahiro, a charming, popular high school student, harbors a terrible secret: though he appears to be male, the lower half of his body is female. At a nurse’s urging, he agrees to visit the school infirmary for a series of dream workshops in which he interacts with classmates who are also grappling with serious problems, from child abuse to pathological insecurity. The students’ collective dreams are vivid and strange, unfolding with the peculiar, fervid logic of a nightmare; buildings flood, stairwells lead to dead ends, and characters undergo sudden, dramatic transformations. Making the dream sequences extra creepy is the way Setona Mizushiro renders the students, choosing an avatar for each that represents their true selves: a black knight, a faceless body, a long, disembodied arm that grasps and slithers. Attentive readers will be rewarded for their patient observation with an unexpected but brilliant twist in the very final pages.

6. The Drifting Classroom

6. The Drifting Classroom

By Kazuo Umezu • VIZ Media • 11 volumes

It’s sorely tempting to compare The Drifting Classroom to The Lord of the Flies, as both stories depict school children creating their own societies in the absence of adult authority. But Kazuo Umezu’s series is more sinister than Golding’s novel, as Classroom‘s youthful survivors have been forced to band together to defend themselves from their former teachers, many of whom have become unhinged at the realization that they may never return to their own time. (Their entire elementary school has slipped through a rift in the space-time continuum, depositing everyone in the distant future.) The story is as relentless as an episode of 24: characters are maimed or killed in every chapter, and almost every line of dialogue is shouted. (Sho’s petty arguments with his mother are delivered as emphatically as his later attempts to alert classmates to the dangers of their new surroundings.) Yet for all its obvious shortcomings, Umezu creates an atmosphere of almost unbearable tension that conveys both the hopelessness of the children’s situation and their terror at being abandoned by the grown-ups. If that isn’t the ultimate ten-year-old’s nightmare, I don’t know what is. —Reviewed at PopCultureShock on 10/15/06

5. Mermaid Saga

5. Mermaid Saga

By Rumiko Takahashi • VIZ Media • 4 volumes

This four-volume series ran on and off in Shonen Sunday for nearly ten years, chronicling the adventures of Yuta, a fisherman who gained immortality by eating mermaid flesh. Desperate to live an ordinary existence, Yuta spends five hundred years wandering Japan in search of a mermaid who can restore his mortality, crossing paths with criminals, immortals, and “lost souls,” people reduced to a monstrous condition by the poison in mermaid flesh. Though the stories follow a somewhat predictable pattern, Takahashi’s writing is brisk and assured, propelled by snappy dialogue and genuinely creepy scenarios. The imagery is tame by horror standards, but Takahashi doesn’t shy away from the occasional grotesque or gory image, using them to underscore the ugly consequences of seeking immortality. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 10/29/09.

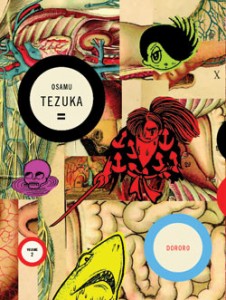

4. Dororo

4. Dororo

By Osamu Tezuka • Vertical, Inc. • 3 volumes

The next time you feel inclined to criticize your parents, remember Hyakkimaru’s plight: his father pledged Hyakkimaru’s body parts to forty-eight demons in exchange for political power, leaving his son blind, deaf, and limbless at birth. After being rescued and raised by a kindly doctor, Hyakkimaru embarks on a quest to reclaim his eyes and ears, wandering across a war-torn landscape where demons take advantage of the chaos to prey on humans. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore (e.g. a nine-tailed fox), while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination (e.g. a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath). Though the story ostensibly unfolds during the Warring States period, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear. For my money, one of Tezuka’s best series, peroid. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 7/27/09

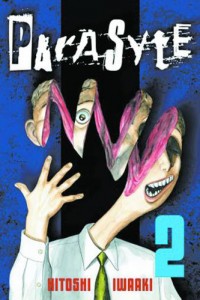

3. Parasyte

3. Parasyte

By Hitoshi Iwaaki • Del Rey • 8 volumes

Part The Defiant Ones, part Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Parasyte focuses on the symbiotic relationship between Shin, a high school student, and Migi, the alien parasite that takes up residence in his right hand after failing to take control of Shin’s brain. The two go on the lam after another parasite kills Shin’s mother — and makes Shin and Migi look like the culprits. If the human character designs are a little blank and clumsy, the parasites are not; Hitoshi Iwaaki twists the human body into some of the most sinister-looking shapes since Pablo Picasso painted Dora Maar. The violence is graphic but not sadistic, as most of the action takes place between panels, with only the grisly aftermath represented in pictorial form. The best part of Parasyte, however, is the script; Shin and Migi trade barbs with the antagonistic affection of Oscar Madison and Felix Unger, revealing Migi to be smarter and more objective than his human host. Shin and Migi’s banter adds an element of levity to the story, to be sure, but their heated debates about survival are also a sly poke at the idea that human beings’ intellect and emotional attachments place them squarely atop the food chain. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 7/2/10

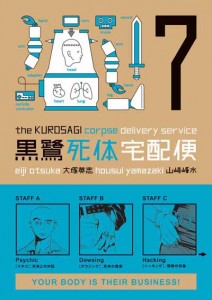

2. The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service

2. The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service

By Eiji Otsuki and Housui Yamakazi • Dark Horse • 13+ volumes

The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service is comprised of five members: Karatsu, a monk-in-training; Numata, a hipster with an encyclopedic knowledge of pop culture; Yata, an odd duck who communicates primarily through a puppet that he wears on his left hand; Makino, a chatty embalmer; and Sasaki, a hacker with an entrepreneurial streak. Working as a team, the quintet helps the dead cross over, using their myriad talents to locate bodies, speak with ghosts, and resolve the spirits’ unfinished business. The set-up is pure gold, giving the episodic series some structure, while allowing Eiji Otsuka and Housui Yamakazi the flexibility to stage grisly murders and discover corpses in a variety of unexpected places. Think Scooby Doo with less wholesome protagonists and scarier spooks and you have a good idea of what makes this offbeat series tick. And yes, the gang even has their own van. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 6/24/09

1. Gyo

By Junji Ito • VIZ Media • 2 volumes

From the standpoint of craft, Uzumaki is a better manga, but it’s hard to top the sheer creepiness factor of Gyo, which taps into one of the most primordial of fears: being eaten! Here’s how I explained its appeal to David Welsh at The Comics Reporter:

Like many other children of the 1970s, Jaws left an indelible impression on me. I wasn’t just terrified of swimming in the ocean, I was reluctant to immerse myself in any standing body of water — swimming pools, bathtubs, ponds — that might conceivably harbor a shark. That irrational fear of encountering a great white somewhere it’s not supposed to be even led me to wonder what it might be like to bump into one on land — could I outrun it?

I’m guessing Junji Ito also suffers from icthyophobia, because Gyo looks like my worst nightmare, a world in which hideously deformed fish crawl out of the sea on mechanical legs and terrorize humans, spreading a disease that quickly jumps species. As horror stories go, many of Gyo‘s details aren’t terribly well explained — how, exactly, the fish acquired legs remains unclear despite talk of military experiments gone awry — but the imaginative artwork appeals on a visceral level. Gyo‘s highpoint comes midway through volume one, when a great white shark chases the hero and his girlfriend through a house, even scaling the stairs (no pun intended) in pursuit of its next meal. The scene is utterly ridiculous, but it works — for a few terrible, thrilling pages I learned the answer to my long-standing question, What would it be like to be chased by a shark on land? In a word: scary.

In other words, this is my worst nightmare:

So those are ten of my favorite spooky manga! What horror manga are on your top-ten list? Inquiring minds want to know!

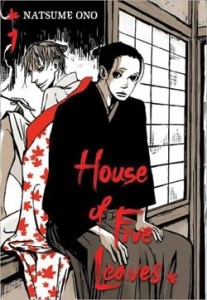

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom.

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, before publishers realized that they could sell manga to teenagers through Borders and Books-A-Million, VIZ and Dark Horse actively courted the comic-store crowd with blood, bullets, and boobs. It was a golden age for manly-man manga — think Crying Freeman and Hotel Harbor View — but it was also a period in which publishers licensed some bad stuff. And when I say “bad stuff,” I mean it: I’m talking ham-fisted dialogue, eyeball-bending artwork, and kooky storylines that defy logic. Lycanthrope Leo (1997), an oddity from the VIZ catalog, is one such manga, a horror story with a plot that might best be described as Teen Wolf meets The Island of Dr. Moreau with a dash of WTF?!

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, before publishers realized that they could sell manga to teenagers through Borders and Books-A-Million, VIZ and Dark Horse actively courted the comic-store crowd with blood, bullets, and boobs. It was a golden age for manly-man manga — think Crying Freeman and Hotel Harbor View — but it was also a period in which publishers licensed some bad stuff. And when I say “bad stuff,” I mean it: I’m talking ham-fisted dialogue, eyeball-bending artwork, and kooky storylines that defy logic. Lycanthrope Leo (1997), an oddity from the VIZ catalog, is one such manga, a horror story with a plot that might best be described as Teen Wolf meets The Island of Dr. Moreau with a dash of WTF?!