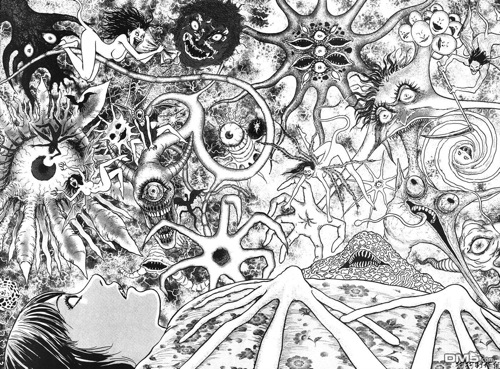

Uncanny–that’s the first word that comes to mind after reading Junji Ito’s Fragments of Horror, an anthology of nine stories that run the gamut from deeply unsettling to just plain gross. Ito is one of the few manga-ka who can transform something as ordinary as a mattress or a house into an instrument of terror, as the opening stories in Fragments of Horror demonstrate. Both “Futon” and “Wood Spirit” abound in vivid imagery: apartments infested with demons, floors covered in eyes, walls turned to flesh, rooves thatched in human hair. Watching these seemingly benign objects pulse with life is both funny and terrifying, a potent reminder of how thin the dividing line between animate and inanimate really is.

Taut–that’s another word I’d use to describe Fragments of Horror. Each story is a model of economy, packing 60 or 70 pages of narrative into just 20 or 30. “Dissection Chan,” for example, explores the forty-year relationship between Tatsuro, a surgeon, and Ruriko, a woman who’s obsessed with vivisection. In a brief flashback to Tatsuro’s childhood, Ito documents the unraveling of their friendship, capturing both Ruriko’s escalating desire to cut things open and Tatsuro’s profound shame for helping her procure the tools (and animals) necessary for her experiments. Three or four years have been packed into this seven-page vignette, but Ito never resorts to voice-overs or thought balloons to explain how Tatsuro feels; stark lighting, lifelike facial expressions, and evocative body language convey Tatsuro’s emotional journey from curious participant to disgusted critic.

Not all stories land with the same cat-like tread of “Dissection Chan.” “Magami Nanakuse,” a cautionary tale about the literary world, aims for satire but misses the mark. The central punchline–that authors mine other people’s suffering for their art–isn’t executed with enough oomph or ick to make much of an impression. “Tomio • Red Turtleneck” is another misfire. Though it yields some of the most squirm-inducing images of the collection, it reads like a sixteen-year-old boy’s idea of what happens if your girlfriend discovers that you’ve been stepping out on her: first she’s angry at you, then she’s angry at the Other Woman, and finally she forgives you after you grovel and suffer. (In Tomio’s case, suffering involves grotesque humiliation with a cockroach–the less said about it, the better.)

Taken as a whole, however, Fragments of Horror is testament to the fecundity of Ito’s imagination, and to his skill in translating those visions into sharp, unforgettable illustrations like this one:

PS: I recommend pairing this week’s review with 13 Extremely Disturbing Junji Ito Panels, a listicle compiled by Steve Fox. (The title is a little misleading: the images are unsettling, but are generally SFW.)

Fragments of Horror

By Junji Ito

Rated T+, for older teens

VIZ Media, $17.99

This review originally appeared at MangaBlog on July 17, 2015.