Fullmetal Alchemist, Vol. 21

By Hiromu Arakawa

Published by Viz Media

Winry makes her way safely back to Resembool only to discover that Ed has beaten her to it. Though she’s grateful to find him all in one piece, she’s less thrilled with his insistence that she flee the country. Meanwhile, Al has encountered newly-uncovered homunculus Pride (aka Selim Bradley), whose terrifying power is enough to take control of him and set him against his own brother. Only the the surprise appearance of an old ally can turn this fight around! Now with President Bradley and his dangerous son out of Central City, Mustang’s group of rebels finally makes their move, taking the President’s wife hostage. Can they be prepared for the result?

After the last volume’s calm before the storm, Arakawa ramps up the tension by revealing the true horror of Pride’s power, wrapped up in the package of a cute little boy–one so ruthless he’ll consume his own allies if it will help him to win. Even so, Arakawa manages to balance this kind of pure evil with just the smallest drop of pathos, keeping the story from ever settling into comfortable black and white. This is one of her most impressive (and consistent) balancing acts and part of what makes her story so powerful. The series somehow maintains both pure-hearted shonen morality and multiple shades of gray, side by side, even in its primary characters. It is dark, but never pessimistic–moralistic, but never self-righteous. It follows established conventions of its genre without ever losing its persistent freshness.

Though the story’s increasingly serious bent has (understandably) overwhelmed its early humor, especially now as the climax draws near, there is still quite a bit to be found, particularly in the wonderfully dry humor of Major General Olivier Armstrong and pretty much anyone associated with Colonel Mustang. As the series reaches further into darkness and anxiety, these characters help keep the atmosphere from becoming too heavy, something I expect we’ll all be grateful for by series’ end.

“Tension” is the keyword in this harrowing volume of one of my favorite series in current publication. Keep a look out for tomorrow’s installment of Manga Recon‘s Manga Minis to see how things explode in the series’ next volume!

Review copy provided by the publisher.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

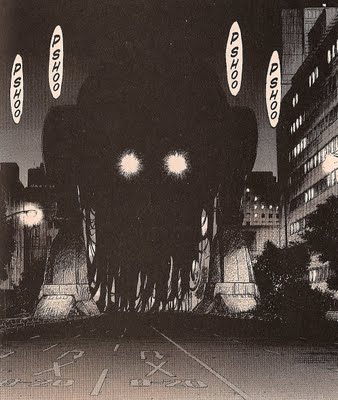

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.