Welcome to another Manhwa Monday!

Welcome to another Manhwa Monday!

It’s a fairly quiet month for manhwa releases, with the only new print volumes coming from Yen Press, including the final volume of Pig Bride. Other releases include volume twelve of Angel Diary, volume five of Sugarholic, volume three of Jack Frost, and my personal pick of the bunch, volume three of Yun JiUn’s collection of ghost stories, Time and Again.

Time and Again has gotten quite a bit of attention this past week, beginning with the recent Off the Shelf column, in which Michelle Smith and I discuss the series’ first volume. Michelle later makes good on her promise to review volumes 1-3 at Soliloquy in Blue.

Then, at Manga Maniac Cafe, Julie takes a look at volume three, “Wow, this series really hits its stride with this volume. Each of the chapters held me enthralled…

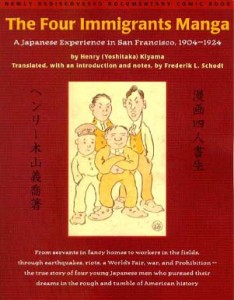

The Four Immigrants Manga

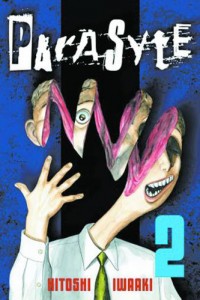

The Four Immigrants Manga Parasyte

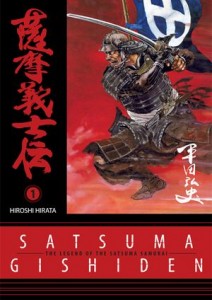

Parasyte Satsuma Gishiden

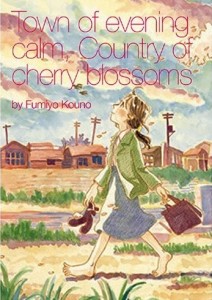

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

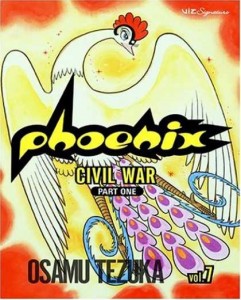

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

PINEAPPLE ARMY

PINEAPPLE ARMY About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima.

About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima.