If you ever wondered what Freaky Friday might have been like if Jodie Foster had switched bodies with Leif Garrett instead of Barbara Harris, well, Ai Morinaga’s Your & My Secret provides a pretty good idea of the gender-bending weirdness that would have ensued. The story focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. Though Akira’s classmates find him “cute and delicate,” they declare him a timid bore — “a waste of a man,” one girl snipes — while Nanako’s peers call her “the beast” for her aggressive personality and uncouth behavior, even as the boys concede that Nanako is “hotter than anyone.” Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. With the flick of a switch, Akira finds himself trapped in Nanako’s body (and vice versa).

The joke, of course, is that Nanako and Akira have found the ideal vessels for their gender-atypical personalities. Nanako revels in her new-found freedom as a boy, enjoying sudden popularity among classmates, earning the respect of Akira’s contemptuous little sister, and discovering the physical strength to dunk a basketball. Akira, on the other hand, finds his situation a mixed bag: for the first time in his life, his sensitive personality endears him to both male and female peers, but many of the things his maleness had previously exempted him from — housework and cooking, menstrual cycles, unwanted advances from boys — turn out to be much worse than he’d imagined. He struggles to feel comfortable in Nanako’s skin, insulted by the grandfather’s refusal to do chores and bewildered by his old buddy Senbongi’s growing attraction to him.

Much of the humor in Your & My Secret stems from the war between head and hormones. Akira still identifies as a boy, lusting after Nanako’s sweetly feminine friend Shiina and suffering volcanic nosebleeds in the girls’ locker room, yet his body is drawn to Senbongi; after Senbongi makes a pass at him, the flustered Akira wonders how Senbongi “got to be such a good kisser.” Nanako, who is quick to embrace her new male identity, struggles as well; though she asks Shiina out, she’s reluctant to consummate their relationship, and shows an all-too-prurient interest in Senbongi’s, um, equipment. Making things even more complicated for Akira is that he’s trapped in the body of the girl he adores. He’s both disgusted and aroused by the sight of himself, and filled with conflicting emotions about the growing relationship between Nanako and Shiina.

Perhaps the most interesting wrinkle in Your & My Secret is that Nanako’s experiences transform her into a sexist pig. She rebuffs Akira’s pleas to reverse the experiment, belittling his gentle, conciliatory personality and asserting her right to have fun in his body. At the same time, she insists that Akira refrain from dating, having sex, or exploring her body; she repeatedly describes her body as a sacred temple that must remain “unpolluted” before her wedding day, and threatens Akira with humiliation if he acts on his conflicted feelings for Senbongi — or Shiina. (Apparently, Nanako is a bit of a homophobe, too.)

While the gender-swapping hijinks provide most of the comedic fodder for Your & My Secret, Morinaga also has a ball poking fun at manga tropes from incestuous infatuation to cultural festivals. The best of these gags revolves around the school’s manga club: in a sly nod to Tezuka, the group is helmed by a beret-wearing artist who transforms Akira and Senbongi’s friendship into a steamy boys’ love comic in which Akira is the seme and Senbongi is the uke. (“It’s not that I like guys,” Akira’s avatar tells Senbongi’s. “The person I fell in love with just happened to be a guy.”) Morinaga also wrings laughs from her characters’ desperate behavior; the grandfather, for example, thinks nothing of blackmailing Akira to get closer to Shiina (he dreams of having a pretty teenage girl sit in his lap and clean his ears), while Senbongi hatches up a love-hotel scheme to drive a wedge between Akira and Nanako.

Yet for all the black comedy, Morinaga still allows her characters moments of vulnerability and decency, preventing the humor from curdling into pure meanness. She wisely avoids the trap of making her characters too dumb to notice the transformations in Akira and Nanako, allowing her to sustain the body-swapping premise without straining credulity or testing the reader’s patience. Morinaga avoids another trap as well: that of making her leads so repellent the reader wishes for their comeuppance. (Even Nanako — she of the karate chops and withering put-downs — demonstrates a capacity for kindness and selflessness when wooing Shiina.) The artwork supports Morinaga’s characterizations, showing us both their nastier and nicer sides. When Akira assumes ownership of Nanako’s body, for example, there’s a visible softening of Nanako’s features, her lips becoming moistly inviting, her chin turning ever-so-slightly upward, and her eyes shining like a proper shojo heroine’s. If provoked, however, Akira’s body language and gestures revert back to Nanako’s coarse, tomboy persona, right down to the maniacal gleam in his eye; the gap between the two personalities proves smaller than either would like the admit.

No, it isn’t Taming of the Shrew, but Your & My Secret manages to make some worthwhile points about gender roles (and gender norms) while serving up plenty of dopey slapstick and risque jokes. Frankly, I’d take a big helping of Morinaga’s un-PC humor over an earnest, socially responsible “girls’ comic” any day of the week. Highly recommended.

This is an expanded version of a review that originally appeared at PopCultureShock on 3/12/08. The original review can be read by clicking here.

Kingyo Used Books starts from a simple premise: an eccentric group of people run a second-hand bookstore in an out-of-the-way location. Various customers stumble upon the shop — usually by accident — and, in the process of browsing, find a manga that helps them reconnect with a part of themselves that’s been suppressed, whether it be a youthful capacity for romantic infatuation or a desire to paint expressively.

Kingyo Used Books starts from a simple premise: an eccentric group of people run a second-hand bookstore in an out-of-the-way location. Various customers stumble upon the shop — usually by accident — and, in the process of browsing, find a manga that helps them reconnect with a part of themselves that’s been suppressed, whether it be a youthful capacity for romantic infatuation or a desire to paint expressively. Part Bad News Bears, part Boys of Summer, Diamond Girl follows a time-honored sports-comedy formula in which a team of losers have their pennant dreams rekindled after an unlikely but undeniable talent joins their ranks. In Diamond Girl, those hard-luck athletes are Baba, Seto, and Takagi, the heart and soul of the Ryukafuchi High School baseball club. The trio discovers, by accident, that the new transfer student has the throwing arm of a youthful Roger Clemens, capable of nailing a moving object hundreds of feet away or throwing a shotput with the ease and precision of a softball. The catch: Tsubara is a girl, making her ineligible to play.

Part Bad News Bears, part Boys of Summer, Diamond Girl follows a time-honored sports-comedy formula in which a team of losers have their pennant dreams rekindled after an unlikely but undeniable talent joins their ranks. In Diamond Girl, those hard-luck athletes are Baba, Seto, and Takagi, the heart and soul of the Ryukafuchi High School baseball club. The trio discovers, by accident, that the new transfer student has the throwing arm of a youthful Roger Clemens, capable of nailing a moving object hundreds of feet away or throwing a shotput with the ease and precision of a softball. The catch: Tsubara is a girl, making her ineligible to play. 10. DEJA-VU: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER

10. DEJA-VU: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER 9. NARRATION OF LOVE AT 17

9. NARRATION OF LOVE AT 17 8. PRIEST

8. PRIEST 7. RUN, BONG-GU, RUN!

7. RUN, BONG-GU, RUN! 6. 10, 20, AND 30

6. 10, 20, AND 30 5. GOONG: THE ROYAL PALACE

5. GOONG: THE ROYAL PALACE 4. FOREST OF GRAY CITY

4. FOREST OF GRAY CITY 3. SHAMAN WARRIOR

3. SHAMAN WARRIOR 2. DOKEBI BRIDE

2. DOKEBI BRIDE 1. BUJA’S DIARY

1. BUJA’S DIARY

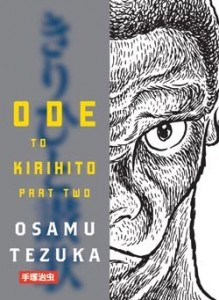

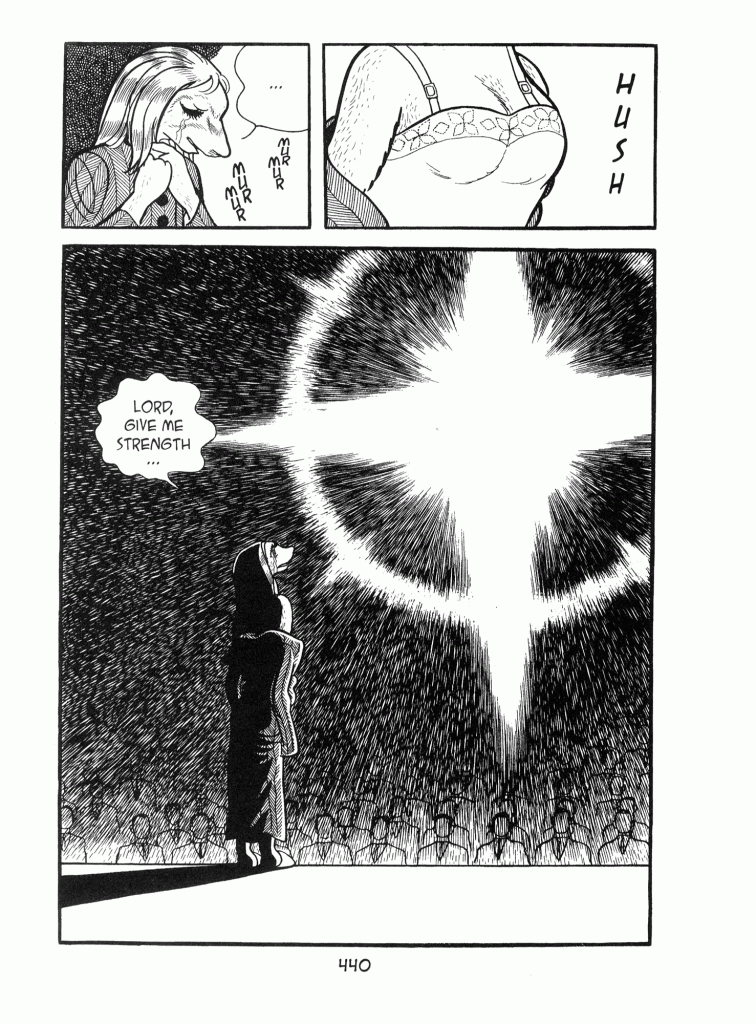

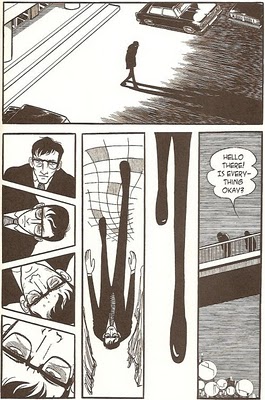

“When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment.

“When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment. At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

As a feminist, yaoi puts me in a difficult position. On the one hand, I love the idea of women creating erotica for other women, of creating a safe and fun space where female readers can explore their sexual fantasies. (I don’t know about you, but Ron Jeremy has never factored into any of mine.) On the other hand, I’m often uncomfortable by the way in which rape is conflated with extreme romantic desire in yaoi; it’s disappointing to see the “you’re so irresistible, I couldn’t help myself!” defense trotted out as a justification for sexual violation. To be sure, the rape-as-love trope abounds in romance novels and mainstream pornography as well, but as a feminist, it makes me just as uncomfortable to encounter it in yaoi as it does to encounter it in an episode of General Hospital. Then, too, there’s the issue of the characters’ homosexuality, which is sometimes trivialized (i.e., they’re not gay, they’re just so good-looking they couldn’t help themselves!), ignored, or “explained” by a character’s tragic past, as if sexual orientation were a simple, situational decision.

As a feminist, yaoi puts me in a difficult position. On the one hand, I love the idea of women creating erotica for other women, of creating a safe and fun space where female readers can explore their sexual fantasies. (I don’t know about you, but Ron Jeremy has never factored into any of mine.) On the other hand, I’m often uncomfortable by the way in which rape is conflated with extreme romantic desire in yaoi; it’s disappointing to see the “you’re so irresistible, I couldn’t help myself!” defense trotted out as a justification for sexual violation. To be sure, the rape-as-love trope abounds in romance novels and mainstream pornography as well, but as a feminist, it makes me just as uncomfortable to encounter it in yaoi as it does to encounter it in an episode of General Hospital. Then, too, there’s the issue of the characters’ homosexuality, which is sometimes trivialized (i.e., they’re not gay, they’re just so good-looking they couldn’t help themselves!), ignored, or “explained” by a character’s tragic past, as if sexual orientation were a simple, situational decision.

Oh, Natsume Ono, I just can’t quit you! I was not wild about

Oh, Natsume Ono, I just can’t quit you! I was not wild about