Kazuo Umezu’s writing defies easy categorization. His horror stories unfold in an almost haphazard fashion, seldom offering Western readers the kind of inevitable showdown between supernatural menace and righteous avenger that’s de rigeur in grindhouse flicks. In a less charitable mood, I might suggest that Umezu was simply making it up as he went along, adding whatever Grand Guignol flourishes tickled his fancy; in a more critically responsible frame of mind, I’d argue that Umezu uses non-sequitors, heightened realism, and Freudian imagery to create a hallucinatory atmosphere that thumbs its nose at logic or teleology.

In the afterword to Cat-Eyed Boy, artist Mizuho Hiroyama offers a more geneorus assessment of Umezu’s approach to storytelling:

But just what is this unforgettable bizarreness that lies at the core of Umezu’s world? Is it a child’s nightmare? I think that this probably the best way to describe it. It’s simply fear. The escalating fear and imagination of a child who is unable to fall asleep in a pitch-dark room late at night, thinking about the worst-case scenarios and wondering, “What would I do if this happened?”

I think Hiroyama is on to something here: as anyone who’s read The Drifting Classroom knows, that entire series reads like a child’s nightmare, filled with terrifying monsters, barren wastelands, and irresponsible, ineffectual adults whose inability to save the day forces the stranded students to rely on themselves.

These same motifs recur throughout Umezu’s oeuvre. The eleven stories that comprise Cat-Eyed Boy, for example, are chock-full of demons — some grotesque, some comic — vengeful spirits, dead parents, and spiteful adults. Cat-Eyed Boy, a child-like creature who’s half-human, half-demon, finds himself relegated to the margins of both worlds, making him especially vulnerable to predation, in spite of his obvious strength and cunning. Like Sho and his Drifting Classroom peers, Cat-Eyed Boy must frequently outsmart unscrupulous adults (and a few monsters) to save his own skin.

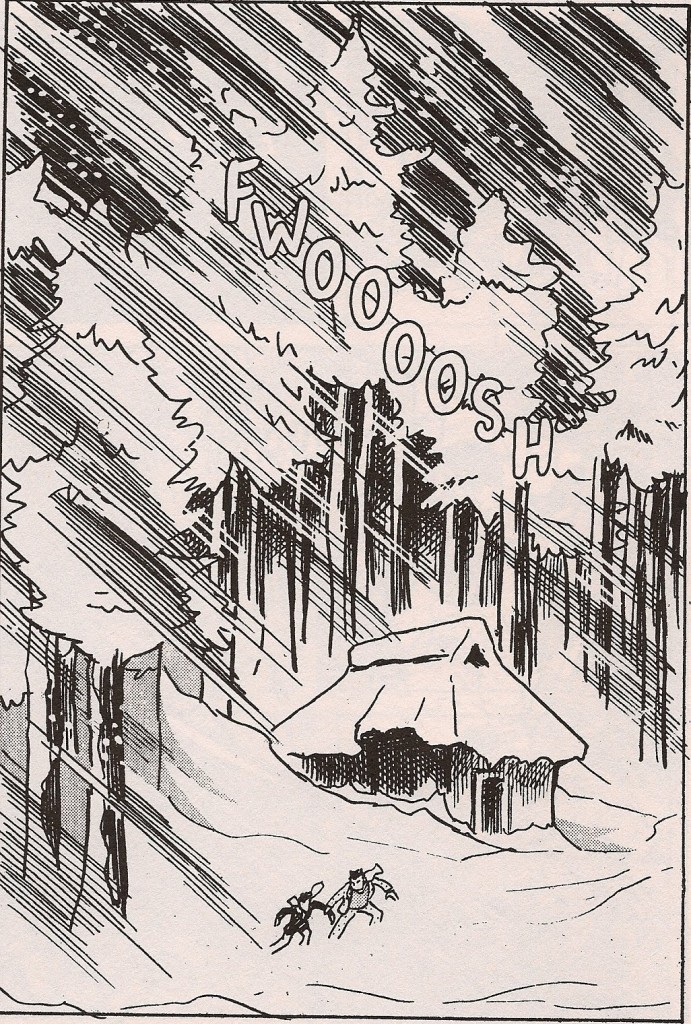

Cat-Eyed Boy’s role varies from story to story: in some, he’s an active participant, a trickster figure who cajoles or deceives, while in others, he’s an observer. The strongest entry of the collection, “The Tsunami Summoners,” is, not coincidentally, the one in which Umezu portrays his odd little hero as a truly grotesque figure, one whose liminal status arouses genuine pity in readers. On one level, “Summoners” is an origin story, explaining where Cat-Eyed Boy came from, how he was exiled from the demon world, and why humans greet him with such suspicion, despite his frequent efforts to intervene on their behalf. On another, it’s a superb example of Umezu-style comeuppance theater, as a small coastal village is punished not only for mistreating one of their own members but for ignoring an ancient warning about a sea-borne menace. Everything about the story works beautifully: the crack pacing, the unforeseen plot twists, and the genuine pathos of Cat-Eyed Boy’s situation as he tries to protect the same villagers who tormented his sole human friend. The summoners are a particularly effective menace, as their initial appearance is relatively benign – they look like brain-shaped rocks, perfect for building walls and houses – allowing them to insinuate themselves into every aspect of the villagers’ lives before anyone is aware of the danger they pose.

Other standouts include “The One-Legged Monster of Ondai,” a cautionary tale about the evils of lepidoptery; “The Thousand-Handed Demon,” a blood bath in which a evil spirit possesses a statue of the Buddhist deity Kwannon; and “The Stairs,” a story about a boy so eager to be see his late mother that he ignores all warnings about the perils of crossing between the lands of the living and the dead.

Several stories were simply too long or scattershot to leave much of an impression. The chief offender is “The Band of One Hundred Monsters,” a rambling tale in which a group of hideously deformed humans aspire to become demons. I thought it was going to be an extended riff on the creative process, as the story initially focuses on the interaction between the “monsters” and a manga-ka known for his bizarre horror tales. Instead, Umezu quickly dispatches the manga-ka and steers the narrative in a wholly unanticipated direction, with the Band of One Hundred murdering pretty yet soulless people. That narrative u-turn does little to bind the two halves of the story together, nor does it take the story in a particularly interesting direction; the notion that beauty is only skin-deep has been explored in countless horror stories to better effect, as Umezu’s earlier work “The Mirror” attests.

Viz presents Cat-Eyed Boy in two generously sized volumes, totaling almost 1,000 pages of story. Both are beautifully packaged, with French flaps, creamy paper stock, and color pages. I particularly liked the endpapers, which catalog the various demons found in both volumes. And what a rogue’s gallery it is — these monsters are considerably more grotesque than anything Umezu conjured for earlier series, sporting myriad eyes, warty skin, tentacles, and grossly misshapen bodies. Most of the stories aren’t terribly spooky or shocking by contemporary standards, but the sheer oddness of the character designs will get under your skin like images from a particularly vivid nightmare.

This is a revised version of a review that appeared at PopCultureShock on August 12, 2008.

CAT-EYED BOY, VOLS. 1 – 2 • BY KAZUO UMEZU • VIZ • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)