The opening pages of Puella Magi Madoka Magica suggest a dreary retread of Sailor Moon: Kyubey, a talking cat, appears before Madoka Kaname, a perky yet otherwise unremarkable school girl, and asks her, “Would you like to change destiny?” Our first clue that Puella has something nastier up its be-ribboned sleeve occurs midway through the first chapter, when transfer student Homura Akemi confronts Madoka with a dire, if cryptic, warning: “You should never consider ‘changing yourself’ in any way,” she tells Madoka. “If you choose not to heed my words, those things that you hold dear will all be lost.” Homura then attacks Kyubey, accusing him of using “dirty tactics” to persuade Madoka to make a contract with him.

Though all the trappings of a traditional magical girl manga are in place — the costume changes, the cute familiars, the teamwork — Puella charts a darker, more violent course than other translated examples of the genre. Homura and Madoka operate in a world where magical girls routinely die; though their powers are formidable, magical girls are worked to the point of emotional and physical exhaustion. Moreover, their contracts are signed under duress; Kyubey frequently appeals to girls in desperate circumstances, using their vulnerability as leverage. (In exchange for battling witches, he explains to Madoka, “I fulfill one wish. Any wish you want!”)

In short, Puella manages to have its cake and eat it, too, faithfully adhering to the genre’s conventions while offering an explicit critique of its underlying message of courage and selflessness. The story is the antithesis of a wish-fulfillment fantasy: the powers that Kyubey bestows come with responsibilities that are too difficult for a young, inexperienced person to bear. Throughout the manga, we see examples of magical girls who have become competitive or embittered by their experiences, at risk of becoming witches themselves. We also meet girls who regret the haste with which they made their contracts, as their wishes were fulfilled at the expense of friends and family members.

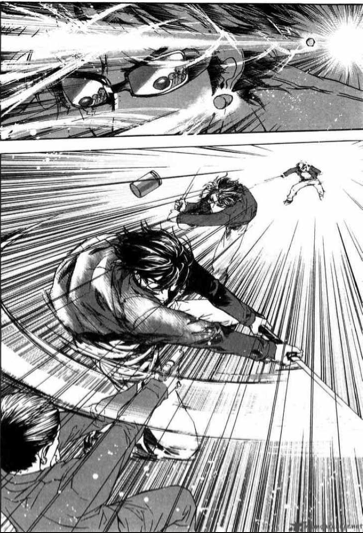

As sharp as Puella‘s genre critique may be, the artwork is a disappointment. The character designs are faithful to the original anime, but the magical elements look smudgy on the page, the product of too much dark grey screentone. The anime’s surreal fight sequences have lost their visual punch as well. Creatures that looked strange and menacing in color have been defanged, reduced to cute video game monsters floating above the picture plane.

Most of the fight scenes have been compressed into a few pages, further curtailing their impact; we barely have time to register who the opponents are before one of the magical girls has eliminated the threat. As a result, the volume’s climatic scene lacks emotional resonance. Though the characters have repeatedly discussed how dangerous their vocation is, the fight is so fleeting and impressionistic that the stakes seem too low to yield such a devastating outcome.

If the artwork lacks the personality of a Magic Knight Rayearth or Cardcaptor Sakura, however, the actual story is on par with the best translated examples of the magical girl manga. Like the aforementioned CLAMP titles, Puella Magi Madoka Magica treats the magical girl as a character worthy of complexity and genuine interiority; the Puella girls may engage in magical combat, but they’re painfully aware that saving the world can be an ugly business — even if they’re wearing smart costumes.

Review copy provided by Yen Press.

PUELLA MAGI MADOKA MAGICA, VOL. 1 • STORY BY MAGICA QUARTET, ART BY HANOKAGE • YEN PRESS • 144 pp. • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)

KATE: If you buy only one manga this week, make it

KATE: If you buy only one manga this week, make it  SEAN: When Yen press announced

SEAN: When Yen press announced  MICHELLE: Having not yet read The Flowers of Evil, and having probably touted Pandora Hearts a time or two in the past, I’ll cast my vote for the fifth volume of

MICHELLE: Having not yet read The Flowers of Evil, and having probably touted Pandora Hearts a time or two in the past, I’ll cast my vote for the fifth volume of

SEAN: Many

SEAN: Many  KATE: Since I’ve plugged InuYasha more times than I can count, I’m going off-list to highlight an awesome graphic novel that’s arriving in stores on Wednesday:

KATE: Since I’ve plugged InuYasha more times than I can count, I’m going off-list to highlight an awesome graphic novel that’s arriving in stores on Wednesday:  BRIGID: OK, I’ll be different and go with

BRIGID: OK, I’ll be different and go with  MJ: Like Brigid, while Sailor Moon is probably my first choice this week, I’ll seize the opportunity to talk about something different, though I may sorely regret it. Back September of 2010, I read the first volume of Hinako Takanaga’s

MJ: Like Brigid, while Sailor Moon is probably my first choice this week, I’ll seize the opportunity to talk about something different, though I may sorely regret it. Back September of 2010, I read the first volume of Hinako Takanaga’s