Reading Osamu Tezuka’s Lost World (1948) reminded me a formative graduate school experience. I was researching George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935), when I stumbled across a blistering review of a composition I’d never heard: Blue Monday (1922), a one-act “jazz opera” that Gershwin composed for Paul Whiteman’s Scandals of 1922. After attending its premiere, Charles Darnton, critic for the New York Tribune, pronounced the project a disaster, an ill-advised attempt to transplant the conventions of verismo opera to a Harlem setting. Blue Monday, he opined, was “the most dismal, stupid, and incredible blackface sketch that has probably ever been perpetrated. In it a dusky soprano finally killed her gambling man. She should have shot all her associates the moment they appeared and then turned the pistol on herself.” (Darnton, 11)

Ouch.

The review piqued my interest, however, prompting me to track down a recording of Blue Monday. Judged against Porgy and Bess, it was an inferior work; as Gershwin biographer Charles Schwartz observed, the music was several degrees removed from jazz and ragtime, drawing its cues from Alexander’s Ragtime Band and not The Maple Leaf Rag. (Schwartz, 61) The dramaturgy, too, was weak, conveying little of the Harlem setting. Yet in this early experiment, I could hear glimmerings of Gershwin’s mature style, a conscious effort to bring African-American music to the opera stage. And that excited me.

I had a similar reaction to Lost World, an early, problematic work in the Tezuka canon. First published in 1948, Lost World focuses on a scientific expedition to the fictional planet Mamango, a large, egg-shaped rock that, five million years earlier, had been a part of the Earth. When the scientists arrive on Mamango, they discover a Jurassic landscape carpeted in monstrous ferns, populated by hungry dinosaurs, and littered with powerful “energy stones.” The financial and scientific value of their discoveries, however, soon cause a deadly rift within the expedition party.

I had a similar reaction to Lost World, an early, problematic work in the Tezuka canon. First published in 1948, Lost World focuses on a scientific expedition to the fictional planet Mamango, a large, egg-shaped rock that, five million years earlier, had been a part of the Earth. When the scientists arrive on Mamango, they discover a Jurassic landscape carpeted in monstrous ferns, populated by hungry dinosaurs, and littered with powerful “energy stones.” The financial and scientific value of their discoveries, however, soon cause a deadly rift within the expedition party.

The execution of Lost World will come as a shock to readers familiar with Tezuka’s mature style. The profusion of subplots, minor characters, and doppelgangers makes the story hard to follow on a moment-to-moment basis; without frequent narrative interventions from the characters, large stretches of Lost World would be incomprehensible. More frustrating still is Tezuka’s over-reliance on dialogue to resolve plot points and reveal motive, even when that information is readily conveyed by the pictures. (“This is payback for you throwing me into the gorge! You get me?!” one character yells as he pummels the person who pushed him off a cliff in the previous scene.) The biggest disappointment, however, is the artwork; most of the panels consist of talking heads, with a handful of dramatic, but disjointed, action scenes interrupting the steady stream of chatter.

Writing about Lost World in the 1980s, Tezuka conceded Lost World‘s shortcomings, attributing them to his age (he was 20) and the circumstances of its publication. As he explained, the work originally ran in an Osaka newspaper, Kansai Yoron, where the target audience was young adults. The two-volume version published by Fuji Shobo, however, was aimed at the children’s market, necessitating substantial changes to the the script. What had been a romance in the original version, for example, was recast as a brother-sister relationship in the Fuji Shobo edition; anything more explicit would have been “absolutely taboo in children’s comics” of the period. (Tezuka, 248)

At the same time, Tezuka touted Lost World as an important milestone in his artistic development. “I thought that at the very least, there was no other comic book like mine, which was like a novel (albeit a very crude one), and had an unhappy ending,” Tezuka explained. (Tezuka 247) A careful inspection of Lost World supports Tezuka’s claim for its significance; whatever its shortcomings, many of the characters and themes of his mature works appear in embryonic form in Lost World.

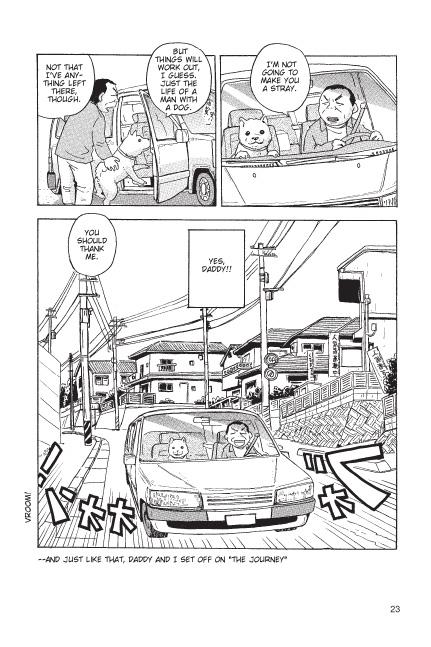

On the most basic level, Tezuka employs several of his best-known “stars” in Lost World, arranging them in contrasting pairs. Acetylene Lamp, for example, plays an unscrupulous journalist who stows away aboard the expedition’s spaceship so that he can get an exclusive scoop on Mamango — and profit from the mysterious “energy stones” scattered across its surface. Another Tezuka favorite, Shunsaku Ban (a.k.a. Higeoyaji), plays yang to Lamp’s yin; as in many of his other incarnations, Ban is a middle-aged detective whose blustery demeanor camouflages his basic decency. Both characters are motivated by curiosity, but their curiosity compels them in opposite directions: Lamp towards profit, Ban towards truth.

From left to right: Acetylene Lamp, Shunsaku Ban/Hygeoyaji, Kenichi Shikishima

The story’s two scientists are likewise played by major “stars” from the Tezuka troupe. Kenichi Shikishima, hero of New Treasure Island, leads the Mamango expedition. Dr. Shikishima’s youthful spirit, resolve, and courage are contrasted with that of Dr. Butaru Makeru, a mustachioed villain whose cowardice and opportunism precipitate the disaster on Mamango. While Shikishima resolves to visit Mamango “for the sake of world science,” Makeru hints at his selfish motives for participating in the expedition: “If by some chance we meet with something unexpected on that planet, don’t blame me. Heh, heh, heh!” That contrast is also underscored by their terrestrial research as well: while Shikishima’s experiments are intended to help animals achieve human consciousness, Makeru’s experiments are designed for his own personal benefit, with little regard for their greater social or scientific good.

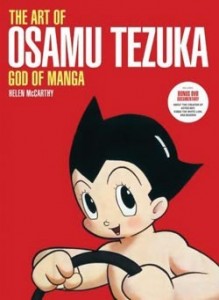

In later works, Tezuka was less schematic in his representations of good and evil, allowing characters to simultaneously embody both. Father Garai, anti-hero of MW, is a good example of this later tendency: Garai is a good man tormented by dark sexual desires, seeking grace even as he sins repeatedly. Black Jack is another, a character whose misanthropy and greed are counterbalanced by a strong reverence for life. As Helen McCarthy observes in The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga, Black Jack is “sometimes a gentle and compassionate savior, sometimes a cold and unforgiving avenger,” two opposite yet equally human responses to “the inevitability of death.” (McCarthy, 199)

Lost World also introduces a recurring character type found throughout Tezuka’s work: the artificial life-form. Early in the story, Tezuka introduces us to Mimio, a talking rabbit, and Ayame, a “veggie girl.” Both are the result of scientific experiments: Dr. Shikishima surgically enhanced Mimio’s brain to grant him human intelligence, while Dr. Butamo cultivated Ayame in a laboratory. (Note that Shikishima’s motives seem benevolent; he wants to help animals achieve equal status with humans, whereas Butamo is more interested in making a wife for himself.)

Mimio and Ayame’s quest for humanity is rather baldly presented. In an early chapter, for example, Mimio visits Shikishima’s lab, where a new group of surgically enhanced animals are learning how to think and act like humans. Though the animals’ struggles with language and manners are played for laughs — “Boy, all humans sure do look alike!” exclaims a dog — there’s a definite sense that these creatures’ own desires are being subordinated to Shikishima’s grander mission of animal-human detente. “You’re very being is unique,” one of Shikishima’s colleagues tells his subjects. “Therefore, you should help humans and be a guide to other animals in perpetuum.”

Unlike Mimio, Ayame looks human, even though she is composed entirely of plant material — and that makes her situation more precarious than the rabbit’s. On the one hand, Dr. Butamo wants her to become his wife, threatening to kill her if she refuses to honor his marriage proposal. On the other, some of the characters view Ayame as nothing more than a walking, talking cabbage — and thus a potential food source when the crew’s rations run out. Ayame remains committed to exploring her humanity nonetheless; late in the manga, she and Shikishima have this pointed exchange:

Shikishima: Miss Ayame, surely, you must be surprised to be having so many adventures.You see? The world of humans is full of adventure and wonder!

Ayame: I feel as if I finally understand what things bring the most pleasure and happiness to the hearts of humans!

Shikishima: Well, then, when you return to the laboratory, you should have Mr. Butamo teach you even more, shouldn’t you?

In Mimio and Ayame, it’s not hard to see the inspiration for later characters such as Dororo‘s Hyakkimaru and Black Jack‘s Pinoko, both of whom struggle to reconcile the circumstances of their “birth” with their desire to be fully human.

Perhaps the most striking thing about Lost World is the final act, in which an accident permanently strands Ayame and Shikishima on Mamango. In Tezuka’s original version, Ayame and Shikishima embrace their fate as lovers, but in the Fuji Shobo edition, Tezuka portrayed them as brother and sister. Nonetheless, Tezuka left the final words of the original intact, speculating that in five million years, “when Mamango once again approaches the Earth,” mankind might find a new race of “plant animal people” descended from Ayame and Shikishima.

Similar Adam-and-Eve motifs recur throughout Tezuka’s oeuvre, finding a more sexual and spiritual expression in such mature works as Apollo’s Song and Phoenix: Nostalgia. Nostalgia is a particularly odd and fascinating variation on the theme, as the Adam figure dies early in the story, leaving his pregnant wife alone on a remote space colony. His wife then mates with her own offspring who, in turn, mate with an extraterrestrial life form whose DNA proves essential to rescuing humanity from the brink of extinction. In short, Nostalgia — like Lost World — dares to a imagine a new future for mankind in which other forms of life — terrestrial and extraterrestrial — play an important role in our evolution.

Whether these observations will make Lost World more palatable to a casual reader is debatable; I fully admit that I struggled through its 246 pages, backtracking frequently in a futile effort to understand what was happening. But if you approach Lost World in the same spirit I approached Gershwin’s Blue Monday — as a window into a major artist’s early development — you may find, as I did, a work of astonishing vibrancy, contradiction, and interest.

Works Cited

“Bet Lost on First Opera.” New York Times. 21 July 1935: II1. Print.

Darnton, Charles. “George White’s Scandals’ Lively and Gorgeous.” New York World 29 Aug. 1922: 11. Print.

McCarthy, Helen, and Osamu Tezuka. The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga. New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2009. Print.

Schwartz, Charles. Gershwin: His Life and Music. New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1973. Print.

Tezuka, Osamu, and Kumar Sivasubramanian. Lost World. Milwaukee, OR: Dark Horse, 2003. Print.