All My Darling Daughters | By Fumi Yoshinaga | Published by Viz Media | Rated T+ (Older Teen)

All My Darling Daughters | By Fumi Yoshinaga | Published by Viz Media | Rated T+ (Older Teen)

Yukiko, nearly thirty and still living at home, is shocked when her widowed mother announces her sudden marriage to a young actor she met at a host club. Suspicious and resentful, Yukiko struggles to hold on to her place in her mother’s life as her entire world shifts around her.

Through a series of interconnected short stories, mangaka Fumi Yoshinaga explores the lives of Yukiko, her friends, her mother, and her grandmother, and how they all relate to one another. Though the stories extend to women in various circumstances–planning their careers as young girls, seeking a husband through arranged marriage, even carrying on an affair with a college professor–what most strikes a personal chord with me is Yoshinaga’s reflections on mothers and daughters as portrayed within three generations of Yukiko’s own family.

The first story begins with a short scene between a teenaged Yukiko and her mother, in which her mother, Mari, rails at her for slovenly habits and general lack of consideration. When Yukiko protests, “You’re just taking your frustration out on me!” her mother replies, “You’re right. That’s exactly what I’m doing! And what’s wrong with that? Parents are human. Sometimes they have bad moods!” Though the truth of that is not something Yukiko wants to hear, when all is said and done, she comes to the realization that all her mother really wants is to be served a cup of tea.

What’s so effective about this scene, is that despite being told from Yukiko’s point of view, Yoshinaga easily reveals the frustrations and vulnerabilities of both characters, as well as their core affection for each other.

What’s so effective about this scene, is that despite being told from Yukiko’s point of view, Yoshinaga easily reveals the frustrations and vulnerabilities of both characters, as well as their core affection for each other.

Later, when Mari’s new husband, Ohashi, moves in, all of these vulnerabilities become even more prominent, as Yukiko stubbornly refuses to like him (which even she can admit is out of pure resentment). This story’s final image, after Yukiko has announced that she will move in with her coworker boyfriend, is a beautiful representation of the relationship between mother and daughter and all the complexity that entails.

Near the end of the volume, Yukiko gains further insight into her mother’s character through some conversation with both her grandmother and her new, young stepfather. What she discovers, of course, is the terrifying truth behind all parenting, which is that the greatest damage is often inflicted with the best intentions.

Having recently discussed another story of mothers and daughters, Kim Dong Hwa’s The Color of… trilogy, I’m struck by the contrast in how they are portrayed. That these stories are very different is certainly to be expected. After all, Kim’s story is set at least a hundred years earlier in an entirely different culture. What’s a bit stunning, however, is how much of this is due to simply to a difference in perspective.

While Kim views the relationship between mother and daughter from the outside, through a lens of reverent nostalgia, Yoshinaga explores the same relationship from a place of intimate understanding. Without the veil of nostalgia as an obstacle, Yoshinaga is able to create fully-realized characters who exist together, not just as mother and daughter, but also as roommates, friends, enemies, nagging burdens, and pillars of support. Though so much of their complicated relationship remains unspoken, it is all there–some lurking just beneath the dialogue, and even more within Yoshinaga’s spare, expressive artwork.

Perhaps it isn’t fair to expect such deep insight into the mother-daughter relationship from a male writer, but I’ll admit it is the lack of complexity in Kim’s portrayal that keeps me from enjoying his series as much as I might. If nothing else, this highlights what makes Yoshinaga’s work so strong, and prompts me to hope that she’ll continue to write more stories about women.

Though I’ve spent most of my time here focusing on the overarching story of Yukiko and Mari, the volume’s other stories are effective as well, particularly one that traces the path of one of Mari’s junior high friends from her youthful ambitions to the adult life she ultimately settles for.

Only one story feels slightly out of place–that of a college professor friend of Ohashi’s who finds himself wrapped up in a relationship with a masochistic student–mainly because it is the only story in the book not told from the perspective of a female character. Yet even this manages to fall into place by the end, as Yoshinaga muses on the value of imperfection and personal idiosyncrasy.

To say that this manga speaks to me on a very personal level seems like a fairly obvious understatement, but I’ll say it anyway. All My Darling Daughters is a must-read for grown-up women everywhere.

Images © Fumi Yoshinaga. Review copy provided by the publisher.

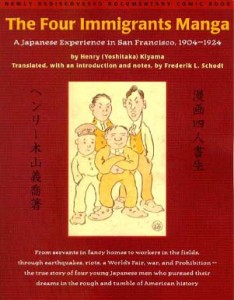

The Four Immigrants Manga

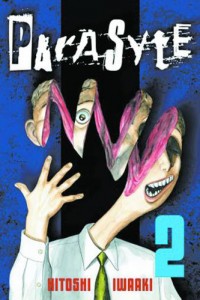

The Four Immigrants Manga Parasyte

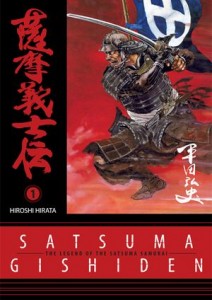

Parasyte Satsuma Gishiden

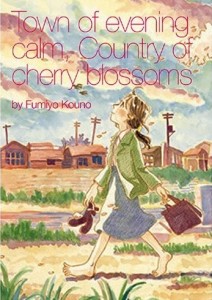

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

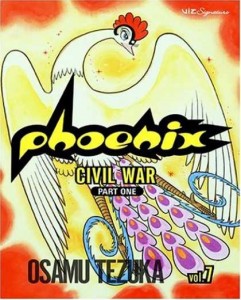

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War