After reading Missin’ and Missin’ 2, I’m convinced that novelist Novala Takemoto was a teenage girl in a previous life. But not the kind of girl who was on the cheerleading squad, the volleyball team, or the school council — no, Takemoto was the too-cool-for-school girl, the one whose unique fashion sense, sullen demeanor, and indifference to high school mores made her seem more adult than her peers, even if her behavior and emotions were, in fact, just as juvenile as everyone else’s. Though this kind of angry female rebel is a stock character in young adult novels, Takemoto has a special gift for making them sound like real girls, not an adult’s idea of what a disaffected teenager sounds like.

After reading Missin’ and Missin’ 2, I’m convinced that novelist Novala Takemoto was a teenage girl in a previous life. But not the kind of girl who was on the cheerleading squad, the volleyball team, or the school council — no, Takemoto was the too-cool-for-school girl, the one whose unique fashion sense, sullen demeanor, and indifference to high school mores made her seem more adult than her peers, even if her behavior and emotions were, in fact, just as juvenile as everyone else’s. Though this kind of angry female rebel is a stock character in young adult novels, Takemoto has a special gift for making them sound like real girls, not an adult’s idea of what a disaffected teenager sounds like.

Consider Kasako, the heroine of Missin’ and Missin’ 2. Kasako feels estranged from her peers’ pop-culture interests, finding refuge in “the antique, the outmoded, indeed, the passe.” Though she has a special affinity for Schubert lieder and Rococo artwork, she finds a kindred spirit in Nobuko Yoshiya, a popular romance novelist whose career spanned the Taisho and Showa periods. Like an earlier generation of schoolgirls, Kasako is enthralled with Yoshiya’s Hana monogatari (Tales of the Flower, 1916 – 1924), a pioneering work of Class S fiction, or stories about romantic friendships between teenage girls.

…

Built in 1607, the Ooku, or “great interior,” housed the women of the Tokugawa clan, from the shogun’s mother to his wife and concubines. Strict rules prevented residents from fraternizing with outsiders, or leaving the grounds of Edo Castle without permission. Within the Ooku, an elaborate hierarchy governed day-to-day life; at the very top were the joro otoshiyori, or senior elders, who supervised the shogun’s attendants and served as court liaisons; beneath them were a web of concubines, priests, pages, cooks, and char women who hailed from politically connected families. This elaborate social system was mirrored in the physical structure of the Ooku, which was divided into three distinct areas — the Rear Quarters, the Middle Interior, and the Front Quarters — each intended solely ladies of a particular rank. The only male permitted into the Ooku (unescorted, that is), was the shogun himself, who accessed the “great interior” by means of the Osuzu Roka, a long corridor that connected the shogun’s living quarters with the imperial harem.

Built in 1607, the Ooku, or “great interior,” housed the women of the Tokugawa clan, from the shogun’s mother to his wife and concubines. Strict rules prevented residents from fraternizing with outsiders, or leaving the grounds of Edo Castle without permission. Within the Ooku, an elaborate hierarchy governed day-to-day life; at the very top were the joro otoshiyori, or senior elders, who supervised the shogun’s attendants and served as court liaisons; beneath them were a web of concubines, priests, pages, cooks, and char women who hailed from politically connected families. This elaborate social system was mirrored in the physical structure of the Ooku, which was divided into three distinct areas — the Rear Quarters, the Middle Interior, and the Front Quarters — each intended solely ladies of a particular rank. The only male permitted into the Ooku (unescorted, that is), was the shogun himself, who accessed the “great interior” by means of the Osuzu Roka, a long corridor that connected the shogun’s living quarters with the imperial harem.

Highbrow, lowbrow… and everything in between. That’s the slogan of

Highbrow, lowbrow… and everything in between. That’s the slogan of  In the year 2346 A.D., humans have colonized the Vulcan solar system, a region so inhospitable that the average life span is a mere thirty years. Rai and Thor, whose parents belong to Vulcan’s ruling elite, enjoy a life of rare privilege — that is, until a political rival executes their parents and exiles the boys to Kimaera, a penal colony reserved for violent criminals. To say Kimaera’s climate is harsh understates the case: daylight lasts for 181 days, producing extreme desert conditions and water shortages, while nighttime plunges Kimaera into arctic darkness for an equal length of time. Making the place even more treacherous is the flora, as Kimaera’s jungles team with carnivorous plants capable of eating humans whole.

In the year 2346 A.D., humans have colonized the Vulcan solar system, a region so inhospitable that the average life span is a mere thirty years. Rai and Thor, whose parents belong to Vulcan’s ruling elite, enjoy a life of rare privilege — that is, until a political rival executes their parents and exiles the boys to Kimaera, a penal colony reserved for violent criminals. To say Kimaera’s climate is harsh understates the case: daylight lasts for 181 days, producing extreme desert conditions and water shortages, while nighttime plunges Kimaera into arctic darkness for an equal length of time. Making the place even more treacherous is the flora, as Kimaera’s jungles team with carnivorous plants capable of eating humans whole. Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone.

Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone. Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots.

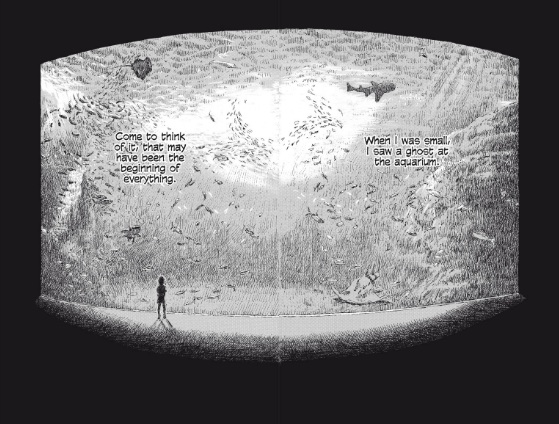

Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots. The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,  Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished.

Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished. For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear.

For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear. Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.”

Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.”