Back in June, Brigid Alverson, Robin Brenner, Martha Cornog and I gave a presentation at the American Library Association’s annual conference called “The Best Manga You’re Not Reading.” Our goal was to remind librarians that manga isn’t just for teens by highlighting fourteen titles that we thought would appeal to older patrons. Response to our presentation was terrific, so I decided to make “The Best Manga You’re Not Reading” a regular feature here at The Manga Critic. Some months I’ll shine the spotlight on something obscure or out-of-print; other months I’ll feature a title that you may have heard about (or even read) because I think it has the potential to appeal to readers who aren’t necessarily mangaphiles. This month’s title — ES: Eternal Sabbath (Del Rey) — was one of Brigid’s picks, a sci-fi manga that she felt had strong visuals and a suitably creepy atmosphere. I couldn’t agree more, so I decided to revise an old review from my PopCultureShock days to explain why you ought to read this trippy, thought-provoking story about the perils of cloning and extrasensory perception.

ES: ETERNAL SABBATH, VOLS. 1-8

ES: ETERNAL SABBATH, VOLS. 1-8

BY FUYUMI SORYO • DEL REY • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)

The vivid images that haunt us when we sleep seem like perfect fodder for art, yet we often produce dream-inspired work that’s much goofier and far less potent than our nocturnal imaginings: think of Salvador Dali’s unabashedly Freudian dream sequence in Spellbound (the one false note in an otherwise great thriller), or John Fuseli’s heavy-handed symbolism in The Nightmare (in which a Rubenesque sleeper is tormented by a ghostly horse and an incubus, the ultimate Romantic two-fer). These images fail to shock because they seem too mannered, too staid — in short, too neat, failing to capture the subconscious mind’s ability to juxtapose the banal with the fantastic. In ES: Eternal Sabbath, however, manga-ka Fuyumi Soryo (best known to American readers for the shojo drama Mars) steers clear of the cliches and overripe imagery that reduce so many dreamy works to kitsch, producing a taut, spooky thriller that reminds us just how weird and terrifying a place the mind can be.

…

Move over, Chucky — there’s a new doll in town.

Move over, Chucky — there’s a new doll in town.

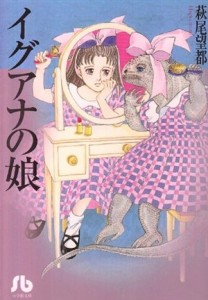

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.

When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side. Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest.

Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest. 5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12 4. X-Day

4. X-Day 3. A.I. Revolution

3. A.I. Revolution 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. Love Song

1. Love Song Duck Prince

Duck Prince Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.) In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”

In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”