Black Jack practices a different kind of medicine than the earnest physicians on Grey’s Anatomy or ER, taking cases that push the boundary between science and science fiction. In the first two volumes of Black Jack alone, the good doctor tests his surgical mettle by:

- Performing a brain transplant

- Separating conjoined twins

- Operating on a killer whale

- Operating blind

- Operating on a man who’s been hit by a bullet train

- Operating on twelve patients at once… without being sued for medical malpractice.

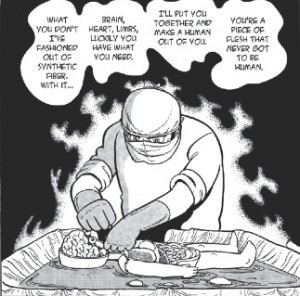

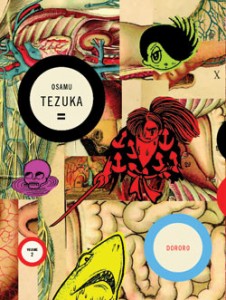

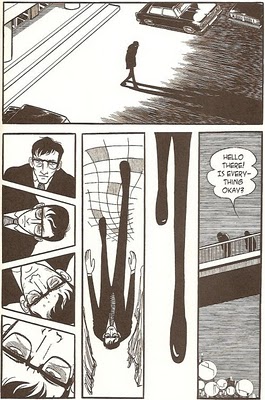

Osamu Tezuka’s own medical training is evident in the detailed drawings of muscle tissue, livers, hearts, and brains. Yet these images are beautifully integrated into his broad, cartoonish vocabulary, making the surgical scenes pulse with life. These procedures get an additional jolt of energy from the way Tezuka stages them; he brings the same theatricality to the operating room that John Woo does to shoot-outs and hostage crises, with crazy camera angles and unexpected complications that demand split-second decision-making from the hero.

At the same time, however, a more adult sensibility tempers the bravado displays of surgical acumen. Black Jack’s medical interventions cure his patients but seldom yield happy endings. In “The Face Sore,” for example, a man seeks treatment for a condition that contorts his face into a grotesque mask of boils. Jack eventually restores the man’s appearance, only to realize that the organism causing the deformation had a symbiotic relationship with its host; once removed, the host proves even more hideous than his initial appearance suggested. “The Painting Is Dead!” offers a similarly bitter twist, as Jack prolongs a dying artist’s life by transplanting his brain into a healthy man’s body. The artist longs to paint one final work — hence the request for a transplant — but finds himself incapable of realizing his vision until radiation sickness begins corrupting his new body just as it did his old one. Jack may profess to be indifferent to both patients’ suffering, insisting he’s only in it for the money, but that bluster conceals a painful truth: Jack knows all too well that he can’t heal the heart or mind.

At the same time, however, a more adult sensibility tempers the bravado displays of surgical acumen. Black Jack’s medical interventions cure his patients but seldom yield happy endings. In “The Face Sore,” for example, a man seeks treatment for a condition that contorts his face into a grotesque mask of boils. Jack eventually restores the man’s appearance, only to realize that the organism causing the deformation had a symbiotic relationship with its host; once removed, the host proves even more hideous than his initial appearance suggested. “The Painting Is Dead!” offers a similarly bitter twist, as Jack prolongs a dying artist’s life by transplanting his brain into a healthy man’s body. The artist longs to paint one final work — hence the request for a transplant — but finds himself incapable of realizing his vision until radiation sickness begins corrupting his new body just as it did his old one. Jack may profess to be indifferent to both patients’ suffering, insisting he’s only in it for the money, but that bluster conceals a painful truth: Jack knows all too well that he can’t heal the heart or mind.

The only thing that dampened my enthusiasm for Black Jack was the outdated sexual politics. In “Confluence,” for example, a beautiful young medical student is diagnosed with uterine cancer. Tezuka diagrams her reproductive tract, explaining each organ’s function and describing what will happen to this luckless gal if they’re removed:

As you know, the uterus and ovaries secrete crucial hormones that define a woman’s sex. To have them removed is to quit being a woman. You won’t be able to bear children, of course, and you’ll become unfeminine.

Too bad Tezuka never practiced gynecology; he might have gotten an earful (and a black eye or two) from some of his “unfeminine” patients.

I also found the dynamic between Jack and his sidekick Pinoko, a short, slightly deformed child-woman, similarly troubling. Though Pinoko has the will and libido of an adult, she behaves like a toddler, pouting, wetting herself, running away, and lisping in a babyish voice. She’s mean-spirited and possessive, behaving like a jealous lover whenever Jack mentions other women, even those who are clearly seeking his medical services. These scenes are played for laughs, but have a creepy undercurrent; it’s hard to know if Pinoko is supposed to be a caricature of a housewife or just a vaguely incestuous flourish in an already over-the-top story. Thankfully, these Pygmalion-and-Galatea moments are few and far between, making it easy to bypass them altogether. Don’t skip the story in which Jack first creates Pinoko from a teratoid cystoma, however; it’s actually quite moving, and at odds with the grotesque domestic comedy that follows.

If you’ve never read anything by Tezuka, Black Jack is a great place to begin exploring his work. Tezuka is at his most efficient in this series, distilling novel-length dramas into gripping twenty-page stories. Though Tezuka is often criticized for being too “cartoonish,” his flare for caricature is essential to Black Jack; Tezuka conveys volumes about a character’s past or temperament in a few broad strokes: a low-slung jaw, a furrowed brow, a big belly. That visual economy helps him achieve the right balance between medical shop-talk and kitchen-sink drama without getting bogged down in expository dialogue. The result is a taut, entertaining collection of stories that offer the same mixture of pathos and medical mystery as a typical episode of House, minus the snark and commercials. Highly recommended.

This is a synthesis of two reviews that originally appeared at PopCultureShock on 10/26/2008 and 11/4/08. I’ve also reviewed volumes five and eleven here at The Manga Critic.

BLACK JACK, VOLS. 1-2 • BY OSAMU TEZUKA • VERTICAL, INC.

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12 4. X-Day

4. X-Day 3. A.I. Revolution

3. A.I. Revolution 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. Love Song

1. Love Song Duck Prince

Duck Prince Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

The Four Immigrants Manga

The Four Immigrants Manga Satsuma Gishiden

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

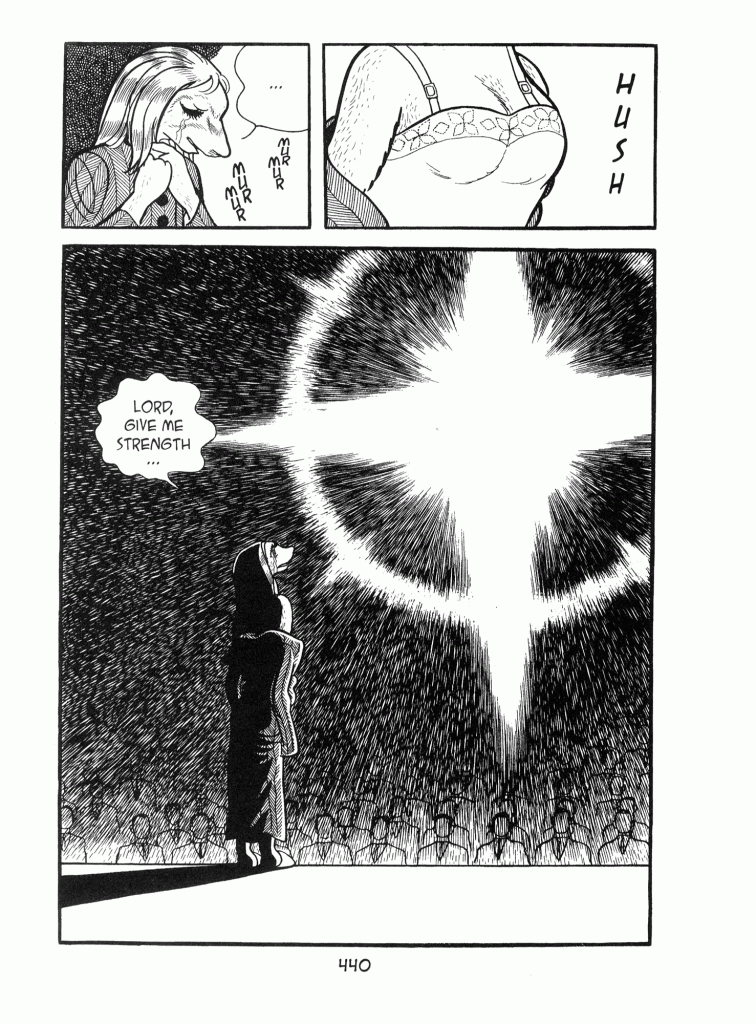

THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924 At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

“When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment.

“When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment.