Can someone who’s never played a Legend of Zelda video game still enjoy the manga adaptations? That’s the question I set out to answer by reading the first two volumes of the Twilight Princess saga.

The short answer to the question is a qualified yes — if by “enjoy” you mean, “get a handle on what’s happening.” Akira Himekawa, a pseudonym for the two-woman team of A. Honda and S. Nagano, pack a considerable amount of exposition into the first two chapters, making it easy for the uninitiated to grasp the premise. Honda and Nagano also use these introductory pages to introduce us to the residents of Ordon Village — the hero’s home — treating us to idyllic scenes of farmers tending their crops, shepherds minding their flocks, and barefoot children cavorting. Though these tableaux are as cornpone as anything John Ford ever committed to screen, they’re rendered in a crisp, readable style that helps the reader understand what’s at stake if Link fails in his quest to restore the balance between light and darkness.

But if you equate “enjoyment” with “feeling a spark of pleasure or surprise while reading,” then the answer to my initial question is a resounding no. There’s a labored quality to the storytelling that prevents Twilight Princess from coming alive on the page; Honda and Nagano try too hard to nail down every narrative detail, producing a story that often reads more like an overly scripted PowerPoint presentation on Twilight Princess than an organic work of fiction. In the first volume, for example, we’re introduced to the obviously pregnant wife of an important supporting character. Just a few pages later, however, another villager helpfully mentions that Uli’s wife is… pregnant. A similar round of no-shit statements accompany Link’s volume two transformation into a wolf, a development that prompts Link — and other characters — to repeatedly observe that he’s no longer human; you could play a decent drinking game by taking a swig of whiskey whenever someone registered surprise at Link’s lupine form. At least he looks cool.

The plot developments are equally obvious. As soon as Honda and Nagano introduced a tremulous teenage girl and her snot-faced little brother, for example, I knew it was only a matter of 30-40 pages before they’d be snatched, giving Link a compelling reason to enter the Twilight Realm. This predictable turn of events wouldn’t be frustrating if we cared about Ilia and Colin’s fate, but they’re such generic characters that they never transcend their function as plot devices. Even the combat feels more like a sprinkling of “adult spice” than a real attempt to tell a darker or more complex story; Twilight Princess is so devoid of ambiguity or suspense that even the most intense, violent sequences seem largely inconsequential.

The blandness of the manga’s execution prompts me to ask a second question: who is Twilight Princess for? Book sales indicate that there’s a large audience of Zelda fanatics who are enjoying this series, so my guess is that the manga appeals to players’ nostalgia for the original games. For the rest of us, however, Twilight Princess is neither interesting nor imaginative enough to compete with One Piece, Naruto, Fairy Tail, or Fullmetal Alchemist on its own terms, nor does it offer any clues why the Zelda games have been a global, thirty-year phenomenon that’s captivated two generations of gamers.

VIZ provided a review copy of volume two.

THE LEGEND OF ZELDA: TWILIGHT PRINCESS, VOLS. 1-2 • BY AKIRA HIMEKAWA • TRANSLATED BY JOHN WERRY • RATED T, FOR TEEN

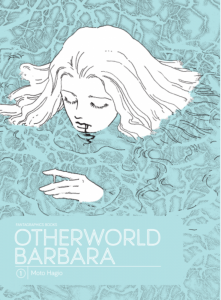

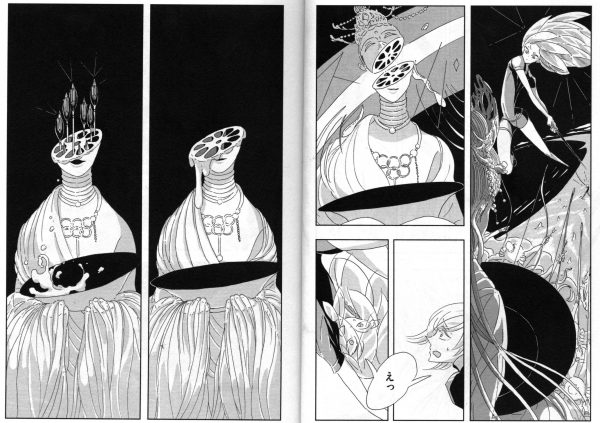

It’s 2052 and Tokio Watarai, a dream pilot, is coming home to Japan for the first time in three years. Although his ex-wife and son are in Japan, he’s actually returning for a job involving a girl who’s been sleeping for seven years since being found with her parents’ hearts in her stomach. Her name is Aoba, and when Tokio enters her dream it’s all about an island called Barbara in which kids can fly and cannibalism factors in to funeral rites. Soon, he learns that his son, Kiriya, actually invented Barbara. So how is Aoba able to dream about it?

It’s 2052 and Tokio Watarai, a dream pilot, is coming home to Japan for the first time in three years. Although his ex-wife and son are in Japan, he’s actually returning for a job involving a girl who’s been sleeping for seven years since being found with her parents’ hearts in her stomach. Her name is Aoba, and when Tokio enters her dream it’s all about an island called Barbara in which kids can fly and cannibalism factors in to funeral rites. Soon, he learns that his son, Kiriya, actually invented Barbara. So how is Aoba able to dream about it?  By the end of the first volume, so very many plot threads are in the air that I was not at all sure that Hagio-sensei would be able to make everything make sense in the end. To use just one example: If Barbara is just a dream—and, indeed, no such island actually exists—then how is it possible that the blood of its residents is used for anti-aging medicine? And yet we see evidence that such advances are already in the works. And because of all this plot stuff, there’s not a lot of time for building solid relationships. There is angst aplenty, especially courtesy of Kiriya, but the whole Marienbad/Tokio hookup, for example, is just extremely random. The strongest bond, though, is definitely the love Tokio feels for his son and his regret over having been a crappy father.

By the end of the first volume, so very many plot threads are in the air that I was not at all sure that Hagio-sensei would be able to make everything make sense in the end. To use just one example: If Barbara is just a dream—and, indeed, no such island actually exists—then how is it possible that the blood of its residents is used for anti-aging medicine? And yet we see evidence that such advances are already in the works. And because of all this plot stuff, there’s not a lot of time for building solid relationships. There is angst aplenty, especially courtesy of Kiriya, but the whole Marienbad/Tokio hookup, for example, is just extremely random. The strongest bond, though, is definitely the love Tokio feels for his son and his regret over having been a crappy father.

I am an enormous fan of Kodansha’s digital offerings, so it pains me to admit that I can’t find anything to recommend about Love’s Reach.

I am an enormous fan of Kodansha’s digital offerings, so it pains me to admit that I can’t find anything to recommend about Love’s Reach. It’s been a long time since I read anything by CLAMP. After failing to love

It’s been a long time since I read anything by CLAMP. After failing to love  It is definitely a good time to be a manga fan, particularly if you (like me) are fond of niche genres like food manga, sports manga, and cat manga. The latest entry into that final category is Plum Crazy! Tales of a Tiger-Striped Cat and, predictably, it’s cute.

It is definitely a good time to be a manga fan, particularly if you (like me) are fond of niche genres like food manga, sports manga, and cat manga. The latest entry into that final category is Plum Crazy! Tales of a Tiger-Striped Cat and, predictably, it’s cute.

I haven’t read a ton of yuri manga, but even I have encountered the “all-girls school with multiple couples” setup before. Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is another example of the same.

I haven’t read a ton of yuri manga, but even I have encountered the “all-girls school with multiple couples” setup before. Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is another example of the same. Volume two introduces still more characters. Ai Uehara doesn’t endear herself to me by whining about the availability of third-year Maya Hoshino—“Mock exams are more important to you than I am!”—and the chapter where she tries to make her friend stay in town rather than going to the university of her dreams and then realizes that this makes her friend sad and then promptly trips and starts blubbering just about had steam coming out of my ears.

Volume two introduces still more characters. Ai Uehara doesn’t endear herself to me by whining about the availability of third-year Maya Hoshino—“Mock exams are more important to you than I am!”—and the chapter where she tries to make her friend stay in town rather than going to the university of her dreams and then realizes that this makes her friend sad and then promptly trips and starts blubbering just about had steam coming out of my ears.