I have good news and bad news for CLAMP fans. The good news is that Gate 7 is one of the best-looking manga the quartet has produced, on par with Tsubasa: Reservoir Chronicles and xxxHolic. The bad news is that Gate 7‘s first volume is very bumpy, with long passages of expository dialogue and several false starts. Whether you’ll want to ride out the first three chapters will depend largely on your reaction to the artwork: if you love it, you may find enough visual stimulation to sustain to your interest while the plot and characters take shape; if you don’t, you may find the harried pacing and repetitive jokes a high hurdle to clear.

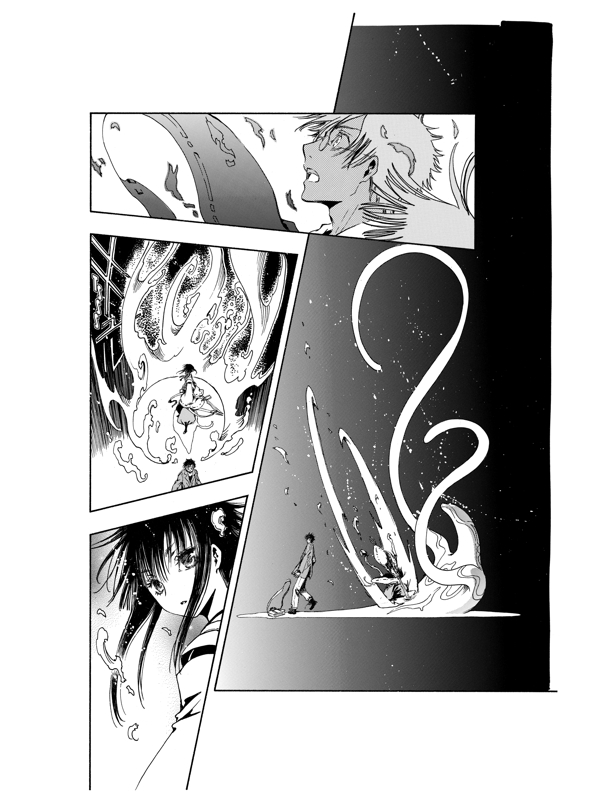

Art-wise, Gate 7 most closely resembles Tsubasa. The character designs are elegantly stylized, rendered in delicate lines; though their proportions have been gently elongated, their physiques are less giraffe-like than the principle characters in Legal Drug and xxxHolic. The same sensibility informs the action scenes as well, where CLAMP uses thin, sensual linework to suggest the energy unleashed during magical combat. (Readers familiar with Magic Knight Rayearth will see affinities between the two series, especially in the fight sequences.) Perhaps the most striking thing about the artwork is its imaginative use of water and light to evoke the supernatural. As Zack Davisson observes in his review of Gate 7, CLAMP uses a subtle but lovely image to shift the action from present-day Kyoto to the spirit realm, depicting the characters as stones in the water, with soft ripples radiating outward from each figure.

The story, however, is less satisfying. The plot revolves around high school student Chikahito Takamoto, a timid dreamer who’s obsessed with Kyoto as a place of “history, ancient arts, temples, and shrines.” While exploring the Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, Chikahito is transported to an alternate dimension, where he encounters three warriors: Sakura, Tachibana, and Hana, an androgynously beautiful, child-like figure who possesses even greater spiritual power than the other two. Chikahito watches the trio dismantle a ribbon-like serpent, but before he can question what he’s seen, poof! he finds himself eating noodles with them in a Kyoto apartment as Sakura and Tachibana debate the ethics of erasing Chikahito’s memory.

The biggest problem with this introductory section is that the subsequent chapter traces a nearly identical trajectory: Chikahito returns to Kyoto, encounters Hana in the streets, then is whisked onto the spirit-plane for another round of magical combat. As soon as the monster is defeated, Chikahito once again finds himself eating a meal with Hana, Sakura, and Tachibana. (This time around, however, they gang-press him into cooking and cleaning for them.) CLAMP even recycles the same gags from the prelude: Hana’s fragile appearance belies a monstrous appetite for noodles, an incongruity CLAMP mines for humor long past the point of being funny.

Other problems prevent Gate 7 from taking flight in its early pages. As we begin to learn more about the Kitano Tenmagu Shrine, for example, various characters take turns explaining its history. These narratives are clearly intended to set the table for a more complex plotline, but have the unintended consequence of stopping the story dead in its tracks. The script also makes some maddening detours into mystical clap-trap; in trying to understand how the seemingly ordinary Chikahito can enter the supernatural realm, characters lapse into Yoda-speak. “We’re alike,” Hana informs Chikahito. When asked, “In what areas?” Hana cheerfully replies, “In areas that are… ‘not.’ Where he’s the same is… ‘not.'”

The most disappointing aspect of Gate 7 is the flimsiness of the characterizations. CLAMP seems to be relying on readers’ familiarity with other titles — Cardcaptor Sakura, Chobits, Tsuaba, xxxHolic — in establishing each character’s personality and role in the drama. Hana, for example, slots into the Mokona role: Hana refers to himself (herself?) in the third person, repeats pet phrases, and behaves like a glutton, yet proves surprisingly powerful. Chikahito, on the other hand, is a carbon copy of xxxHolic‘s Watanuki, a nervous, bespectacled everyman who unwittingly becomes the housekeeper and magical errand-boy for more supernaturally gifted beings. The frantic pace and abrupt transitions between the mundane and supernatural world further complicate the process of establishing Hana and Chikahito as individuals; with so much material stuffed into the first two hundred pages, CLAMP leans too heavily on tics and mannerisms to carry the burden of the characterization. (Cute finger-wagging does not a character make.)

The dramatic introduction of a new character in the volume’s final pages suggests that CLAMP may finally be hitting its stride in chapter four. As promising as this development may be, I can’t quite shake the feeling that I’m reading a Potemkin manga, all surface detail and no depth. Let’s hope volume two proves me wrong.