The scene: a country road in twelfth-century Japan. The players: Yamato, a bandit with a Robin Hood streak; Dr. Dunstan, a Westerner in sunglasses and a flashy yukata; and Yamato’s gang. The robbers surround Dunstan to search his cart for anything of worth, settling on two large crates. Though Dunstan warns them that the consequences of opening the boxes will be dire — “if you wake them, you will die,” he explains — Yamato ignores his advice, prying off the lids to discover what look like two porcelain boys. Both figures spring to life, with Vice — the “ultimate evil one,” in case you didn’t guess from his name — slaughtering six robbers in short order. Though Yamato is badly outclassed — he has a sword, Vice has a variety of lethal powers that would be the envy of the US military — he vows to defend his friends. Yamato’s brave gesture gives the second doll, Ultimo, an opening to jump into the battle and send Vice packing.

The scene: a country road in twelfth-century Japan. The players: Yamato, a bandit with a Robin Hood streak; Dr. Dunstan, a Westerner in sunglasses and a flashy yukata; and Yamato’s gang. The robbers surround Dunstan to search his cart for anything of worth, settling on two large crates. Though Dunstan warns them that the consequences of opening the boxes will be dire — “if you wake them, you will die,” he explains — Yamato ignores his advice, prying off the lids to discover what look like two porcelain boys. Both figures spring to life, with Vice — the “ultimate evil one,” in case you didn’t guess from his name — slaughtering six robbers in short order. Though Yamato is badly outclassed — he has a sword, Vice has a variety of lethal powers that would be the envy of the US military — he vows to defend his friends. Yamato’s brave gesture gives the second doll, Ultimo, an opening to jump into the battle and send Vice packing.

Flash forward to the present: a teenage slacker named Yamato is searching for a one-of-a-kind birthday gift for a pretty classmate when he stumbles across an odd-looking puppet in an antique store. Though Yamato has never seen the puppet before, he’s overwhelmed by a sense of deja vu. Much to his surprise, the puppet’s eyes open, and he lunges forward shouting, “Nine centuries, Yamato-sama! Ultimo missed you very much!” Before Yamato can fully ponder the implications of Ultimo’s outburst, Vice appears on the scene, forcing Yamato and Ultimo into a bus-throwing, glass-shattering smackdown in the streets of Tokyo.

…

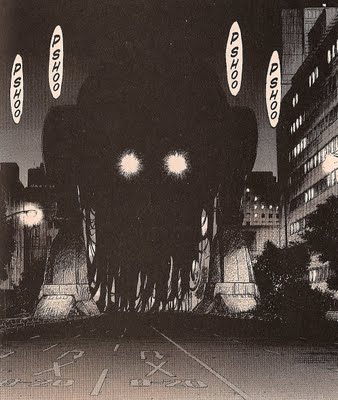

If I’ve learned anything from my limited study of horror films, it’s this: zombies come in two flavors. The first type are slow, shambling, and stupid, posing little threat to the hero until they reach a critical mass — say, enough to surround the pub or shopping mall where the hero has hunkered down to await help. The second type are swift of foot and mind, making them a far greater menace to humanity. Raiders is positively crawling with the second type, giving this preposterous yet entertaining story a jolt of visceral energy. Figuratively and literally.

If I’ve learned anything from my limited study of horror films, it’s this: zombies come in two flavors. The first type are slow, shambling, and stupid, posing little threat to the hero until they reach a critical mass — say, enough to surround the pub or shopping mall where the hero has hunkered down to await help. The second type are swift of foot and mind, making them a far greater menace to humanity. Raiders is positively crawling with the second type, giving this preposterous yet entertaining story a jolt of visceral energy. Figuratively and literally. Two Guys, a Girl, and a Pastry Shop might be a better title for this rom-com about a teen who waits tables at the neighborhood bakery, as the characters are so nondescript I had trouble remembering their names. The girl, Uru, is as generic as shojo heroines come: she’s a spunky, klutzy high school student who blushes and stammers around hot guys, bemoans her flat chest, and wins people over with her intense sincerity. The two guys — Shindo, a moody jerk whose boorishness masks a kind nature, and Ichiro, a cheerful slacker — are just as forgettable, despite the manga-ka’s efforts to assign them novel tics and traits. Shindo, for example, turns out to be a genius who finished high school at fifteen, while Ichiro suffers from hunger-induced narcolepsy, keeling over any time his blood sugar drops.

Two Guys, a Girl, and a Pastry Shop might be a better title for this rom-com about a teen who waits tables at the neighborhood bakery, as the characters are so nondescript I had trouble remembering their names. The girl, Uru, is as generic as shojo heroines come: she’s a spunky, klutzy high school student who blushes and stammers around hot guys, bemoans her flat chest, and wins people over with her intense sincerity. The two guys — Shindo, a moody jerk whose boorishness masks a kind nature, and Ichiro, a cheerful slacker — are just as forgettable, despite the manga-ka’s efforts to assign them novel tics and traits. Shindo, for example, turns out to be a genius who finished high school at fifteen, while Ichiro suffers from hunger-induced narcolepsy, keeling over any time his blood sugar drops. The very first Sinfest strips tell you everything you need to know about Tatsuya Ishida’s cheeky yet surprisingly reverential comic. In them, we see a young man seated at a table across from the Devil, negotiating a contract that would enable him to enjoy — among other perks — a “supermodel sandwich” in exchange for his soul. The transaction isn’t taking place in an office or the gates of Hell, however, but, in a hat tip to Charles Schulz, at a jerry-rigged booth that’s a shoo-in for the one Lucy van Pelt used to dispense nickel-sized bits of wisdom to the Peanuts gang.

The very first Sinfest strips tell you everything you need to know about Tatsuya Ishida’s cheeky yet surprisingly reverential comic. In them, we see a young man seated at a table across from the Devil, negotiating a contract that would enable him to enjoy — among other perks — a “supermodel sandwich” in exchange for his soul. The transaction isn’t taking place in an office or the gates of Hell, however, but, in a hat tip to Charles Schulz, at a jerry-rigged booth that’s a shoo-in for the one Lucy van Pelt used to dispense nickel-sized bits of wisdom to the Peanuts gang. Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters. From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

In The Idea of History, author R. G. Collingwood argues that nineteenth-century historians viewed their task in a different spirit than their predecessors. While previous generations of scholars treated history as a simple chain of events, the Romantics wanted to recreate the past through their writings. The Romantic historian, Collingwood explained, “entered sympathetically into the actions which he described; unlike the scientist who studied nature, he did not stand over the facts as mere objects for cognition; on the contrary, he threw himself into them and felt them imaginatively as experiences of his own.”

In The Idea of History, author R. G. Collingwood argues that nineteenth-century historians viewed their task in a different spirit than their predecessors. While previous generations of scholars treated history as a simple chain of events, the Romantics wanted to recreate the past through their writings. The Romantic historian, Collingwood explained, “entered sympathetically into the actions which he described; unlike the scientist who studied nature, he did not stand over the facts as mere objects for cognition; on the contrary, he threw himself into them and felt them imaginatively as experiences of his own.”

5. Pig Bride

5. Pig Bride  4. Zone-00

4. Zone-00  3. Black Bird

3. Black Bird 2. Lucky Star

2. Lucky Star 1. Maria Holic

1. Maria Holic