Question: what do you get when you cross Sunshine Sketch with X-Men? Answer: A Certain Scientific Railgun, a story about a quartet of schoolgirl psychics who fight crime, go shopping, and eat parfaits. If that combination sounds like the manga equivalent of a peanut butter and tunafish sandwich, it is; the story see-saws between sci-fi pomposity and 4-koma cuteness, never combining these two very different flavors into an appetizing dish.

The story takes place in Academy City, a metropolis whose entire population consists of psychics and psychics-in-training. After a series of bank robberies and bombings, members of Justification, Academy City’s teen police force, make a disturbing discovery: some psychics — or “espers,” in the series’ parlance — are using an illicit drug called Level Upper to enhance their natural ability. (Level Upper is, in essence, steroids for teleporters and mind-readers.) Though the drug grants them tremendous power, that power comes with a terrible price, causing the user to slip into an irreversible coma. The girls must then track the drug to its source before it can spread through Academy City.

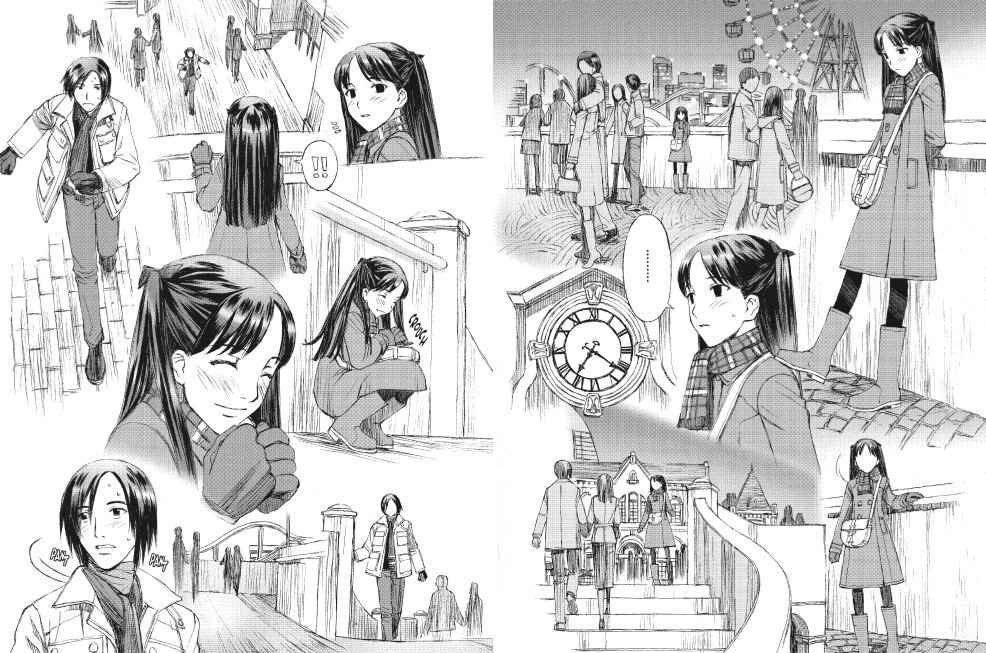

As promising as the plot sounds, it often feels like an afterthought, something that happens in between the principal characters’ trips to the mall, the cafe, and the gym. (There’s an entire scene devoted to one character’s efforts to find the perfect pair of pajamas. No, I’m not kidding.) The lead character, Mikoto, is the strongest and best-defined of the bunch; she’s described as a “level-five esper” capable of channeling up to one billion volts of electricity, a skill she gleefully unleashes on robbers, perverts, and her arch-nemesis, a male psychic named Toma Kamijo. Though Mikoto is an unappealing heroine, she’s the only female character who has a real personality; Mikoto is angry, unpredictable, and stubborn, but she’s also very disciplined, cultivating her skills with practice and study. Kuroko, Ruiko, and Kazari, the remaining members of the quartet, are less developed: each girl has one psychic ability that she uses in combat and one adorable tic that she exhibits while hanging out with friends. (Actually, “adorable” is up for debate; grabbing another girl’s breasts seems more predatory than cute.)

Thin as the characterizations may be, A Certain Scientific Railgun faces an even bigger problem: many important plot elements are poorly explained. Not that the series wants for exposition-dense conversation; the opening ten pages are filled with characters narrating Mikoto’s rise from level-zero nobody to level-five bad-ass. But many other details remain unexplored: who is Toma and why does Mikoto detest him? why do so many characters have supernatural abilities? why has the government created an entire city just for young psychics? Perhaps the most egregious example is Mikoto herself; though we learn a lot about her education, the fact that she’s been cloned is glossed over, as if having six genetic doppelgangers was entirely unremarkable.

Given Railgun‘s origins — it’s a side story within A Certain Magical Index, a long-running light novel series — it’s not surprising that so many of these crucial details remain unexamined; the author might reasonably expect Japanese fans to know the Magical Index universe well enough to jump into Railgun with a minimum of exposition. For a newcomer, however, the experience is frustrating; uninteresting plot points are explored in excruciating detail, while many of the things that seem more fundamental to the story (e.g. the characters’ psychic abilities) are barely addressed at all.

The final chapter suggests that future installments may feature more scenes of crime-solving and fewer scenes of tweenage girls showering, eating desserts, and horsing around. An honest-to-goodness mystery would go a long way towards giving the story some dramatic shape; right now, A Certain Scientific Railgun feels as aimless and airy as a volume of Sunshine Sketch, even if Mikoto and friends have cooler talents than the Sunshine girls.

Review copy provided by Seven Seas. Volume one will be released on June 30, 2011.

A CERTAIN SCIENTIFIC RAILGUN, VOL. 1 • STORY BY KAZUMA KAMACHI, ART BY MOTIO FUYUKAWA • SEVEN SEAS • 192 pp. • RATING: TEEN (13+)