Like Water for Kimchi — that’s how I would describe 13th Boy, a weird, wonderful Korean comedy with a strong element of magical realism.

Like Water for Kimchi — that’s how I would describe 13th Boy, a weird, wonderful Korean comedy with a strong element of magical realism.

The plot is standard sunjong fodder: Hee-So, a teen with a flair for the dramatic, believes that the handsome Won-Jun is destined to be her twelfth and last boyfriend, the man with whom she’ll spend the rest of her life. Though Won-Jun accepts her initial confession of love — she drags him on television to ask him on a date — he dumps her just one month later, sending Hee-So into a tailspin: how could her destiny walk away from her? She then resolves to take fate into her own hands, launching an aggressive campaign to win him back: she stalks Won-Jun, looking for any opportunity to be alone with him; she joins the Girl Scouts so that she can go on a camping trip with him (he’s a Boy Scout); she even befriends her romantic rival Sae-Bom, defending Sae-Bom from bullies and risking her life to rescue Sae-Bom’s beloved stuffed rabbit from a burning building. In short: Hee-So is a girl on a mission, dignity be damned.

…

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

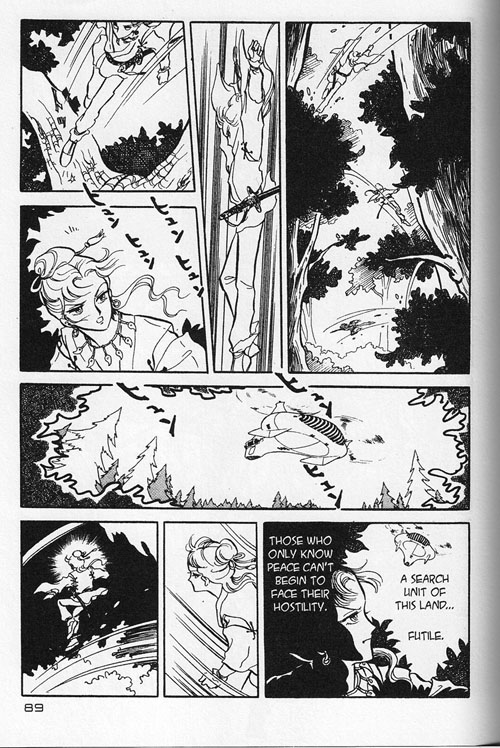

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

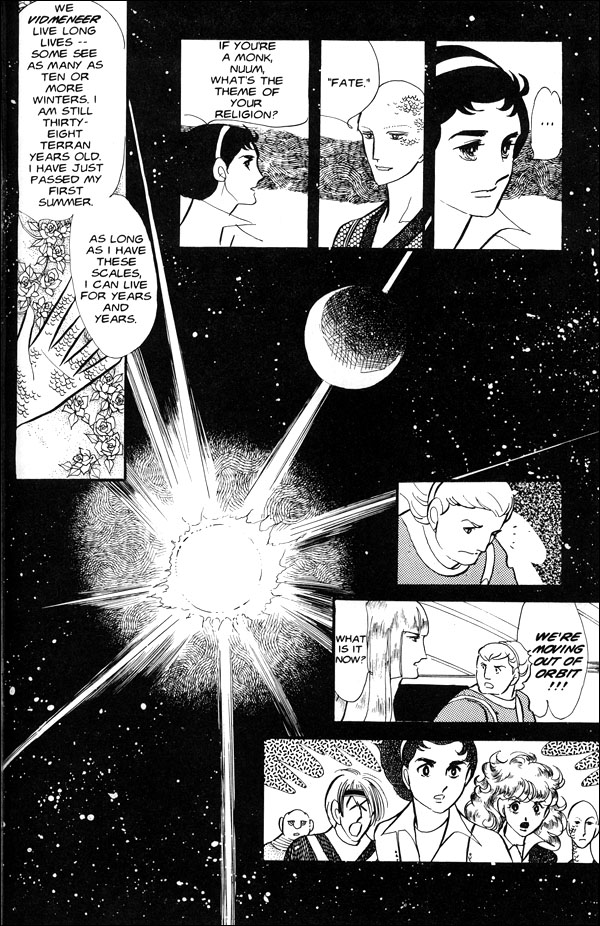

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

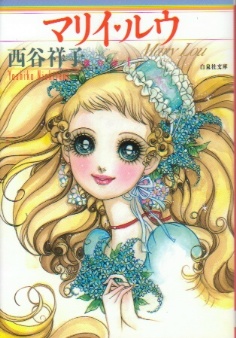

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in  The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.

The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.