I have a special fascination with bad manga. And when I say “bad manga,” I’m not talking about stories that are merely cliche or derivative of other, better series — for better or worse, manga is a popular medium, and popular media survive, in part, by giving audiences what they want, even if that means more of the same — I’m talking about stories so ineptly drawn, so spectacularly dumb, or so offensive that they make Happy Cafe look like Phoenix by comparison. To judge from the coverage of this year’s San Diego Comic-Con, I’m not alone in my connoisseurship of wretched books; among the most widely reported panels was The Best and Worst Manga of 2010, in which a group of seasoned reviewers singled out titles for praise and punishment. To kick off my Bad Manga Week, therefore, I thought it would be a fun exercise to look at three of the titles that made the worst-of list to see if they were truly suited for inclusion in The Manga Hall of Shame. The candidates: Orange Planet (Del Rey), a shojo farce starring one clueless girl and three hot guys; Red Hot Chili Samurai (Tokyopop), a comedy about a hero who favors spicy peppers over PowerBars whenever he needs an energy boost; and Togainu no Chi (Tokyopop), an action-thriller that proudly boasts its origins as a “ground-breaking bishonen game.”

ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1

ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1

BY HARUKA FUKUSHIMA • DEL REY • 200 pp. • TEEN (13+)

Haruka Fukushima specializes in what I call “chastely dirty” manga for tween girls — that is, manga that places the heroine in compromising situations, teasing the audience with the prospect of a kiss or a grope that never quite materializes because the heroine is a good girl, thank you very much. In Orange Planet, Fukushima’s sex-phobic lead is Rui, a junior high student who lives by herself — she’s been an orphan since childhood — and pays for her apartment with a paper route. (That must be some paper route, considering she lives in a modern high-rise apartment and not, say, a cardboard box.) Rui is one corner of a highly contrived love square; the other three points are all standard shojo types, from the boy next door and the hot young teacher to the mystery man from the heroine’s past.

…

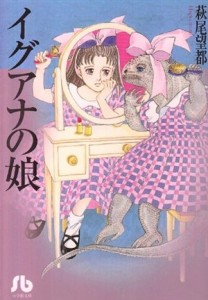

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest.

Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest. 5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.) In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”

In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.” If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life.

If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life. 10. ASTRAL PROJECT

10. ASTRAL PROJECT 9. CHIKYU MISAKI

9. CHIKYU MISAKI 7. SHIRLEY

7. SHIRLEY 6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS

6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS 5. PRESENTS

5. PRESENTS 4. GON

4. GON 3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE

3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE 2. SWAN

2. SWAN 1. EMMA

1. EMMA If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband. A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

If you ever wondered what Freaky Friday might have been like if Jodie Foster had switched bodies with Leif Garrett instead of Barbara Harris, well, Ai Morinaga’s Your & My Secret provides a pretty good idea of the gender-bending weirdness that would have ensued. The story focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. Though Akira’s classmates find him “cute and delicate,” they declare him a timid bore — “a waste of a man,” one girl snipes — while Nanako’s peers call her “the beast” for her aggressive personality and uncouth behavior, even as the boys concede that Nanako is “hotter than anyone.” Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. With the flick of a switch, Akira finds himself trapped in Nanako’s body (and vice versa).

If you ever wondered what Freaky Friday might have been like if Jodie Foster had switched bodies with Leif Garrett instead of Barbara Harris, well, Ai Morinaga’s Your & My Secret provides a pretty good idea of the gender-bending weirdness that would have ensued. The story focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. Though Akira’s classmates find him “cute and delicate,” they declare him a timid bore — “a waste of a man,” one girl snipes — while Nanako’s peers call her “the beast” for her aggressive personality and uncouth behavior, even as the boys concede that Nanako is “hotter than anyone.” Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. With the flick of a switch, Akira finds himself trapped in Nanako’s body (and vice versa).