Altair: A Record of Battles seems tailor-made for fanfic: it’s got a cast of achingly pretty men, a labyrinthine plot, and an exotic setting that freely mixes elements of Turkish, Austrian, and Bedouin cultures. Like other series that inspire such fan-ish activity — Hetalia: Axis Powers comes to mind — Altair is more interesting to talk about than to read, thanks to an exposition-heavy script and an abundance of second- and third-string characters; you’ll need a flowchart to keep track of who’s who.

The first volume begins promisingly enough. While visiting the Türkiye capitol, a diplomat from the neighboring Balt-Rhein Empire is assassinated in the streets, an arrow lodged in his back. Though the murder weapon suggests that someone in the Balt-Rhein military engineered the hit, Emperor Goldbalt’s mustache-twirling subordinate Louis Virgilio points the finger at Türkiye, insisting they produce the killer or face the ultimate consequence: war. Mahmut, the youngest member of the Türkiye generals’ council, impulsively decides to visit Goldblat’s court in an effort to prevent bloodshed and reveal the true culprit in Minister Franz’s death.

No matter how intensely the characters ball their fists or glower at each other, however, their drawn-out arguments over troop mobilization, international diplomacy, and rules of order are only moderately more entertaining than an afternoon of watching C-SPAN. Author Kotono Kato further burdens the script with text boxes indicating characters’ rank and title, and diagrams showing the distribution of power under the Türkiye “stratocracy,” details that add little to the reader’s understanding of why Balt-Rhein and Türkiye are teetering on the brink of war. Only a nighttime ambush stands out for its dynamic execution; it’s one of the few scenes in which Kato allows the pictures to speak for themselves, effectively conveying the ruthlessness of Mahmut’s enemies without the intrusion of voice-overs or pointed dialogue.

The characters are just as flat as the storytelling. Kato’s flair for costume design is symptomatic of this problem: she’s confused surface detail — sumptuous fabrics, towering hats, sparkling jewels — with character development. With the exception of Mahmut, whose passionate intensity and youthful arrogance are evident from the very first scene, the other characters are walking, talking plot devices whose personalities can be summed up in a word or two: “brash,” “devious,” “enthusiastic,” “mean.” (Also “hot” and “well dressed,” for anyone who’s keeping score.) The shallowness of the characterizations robs the Türkiye/Balt-Rhein conflict of urgency, a problem compounded by Kato’s tendency to wrap things up with epilogues that are as baldly worded as a textbook study guide. At least you’ll be prepared for the quiz.

The bottom line: History buffs will enjoy drawing parallels between the Türkiye and Balt-Rhein Empires and their real-life inspirations, but most readers will find Altair too labored to be compelling — unless, of course, they’re looking for fresh opportunities to ‘ship some handsome characters.

ALTAIR: A RECORD OF BATTLES, VOL. 1 • BY KOTONO KATO • KODANSHA COMICS • RATED T, FOR TEENS • DIGITAL ONLY

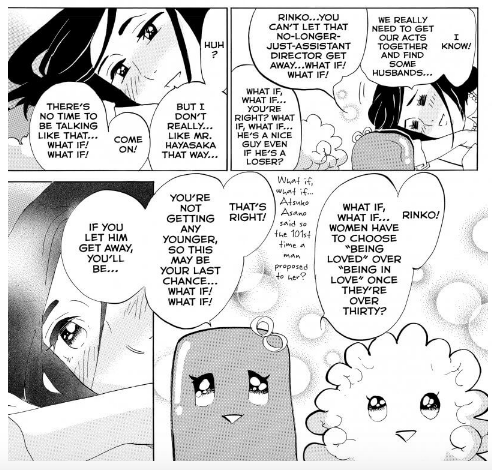

I spent all my time wondering “what if,” then one day I woke up and I was 33.

I spent all my time wondering “what if,” then one day I woke up and I was 33. Chihayafuru is a long-running josei sports manga series about a girl who discovers a passion for the Japanese card game,

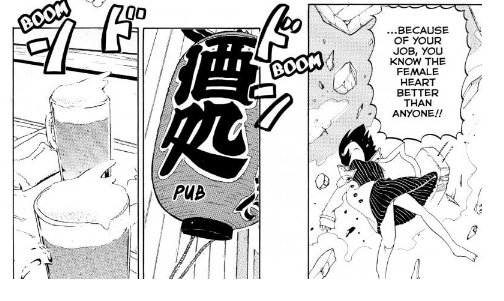

Chihayafuru is a long-running josei sports manga series about a girl who discovers a passion for the Japanese card game,  In the opening scene of Wave, Listen to Me! we meet Minare Koda, an attractive twenty-something drinking too much and pouring her heart out to a guy she just met forty minutes prior. She’s ranting about her ex, Mitsuo, and after a certain point, she has no recollection of events. To her surprise, when she’s at work the next day (as a waitress in a curry shop), she hears her own voice being played over the radio. Turns out, the guy she met was Kanetsugu Mato, who works for a radio station and recorded their conversation. (One of the things she’d forgotten was drunkenly giving her consent.) Minare is temperamental and feisty, so when she marches down to the station to give him a piece of her mind, she ends up going live on the air and impressing Mato with her facility for impromptu eloquence.

In the opening scene of Wave, Listen to Me! we meet Minare Koda, an attractive twenty-something drinking too much and pouring her heart out to a guy she just met forty minutes prior. She’s ranting about her ex, Mitsuo, and after a certain point, she has no recollection of events. To her surprise, when she’s at work the next day (as a waitress in a curry shop), she hears her own voice being played over the radio. Turns out, the guy she met was Kanetsugu Mato, who works for a radio station and recorded their conversation. (One of the things she’d forgotten was drunkenly giving her consent.) Minare is temperamental and feisty, so when she marches down to the station to give him a piece of her mind, she ends up going live on the air and impressing Mato with her facility for impromptu eloquence. Volume two is where things really get great. Mato has inventive ideas for Minare’s show, and I think I will let readers discover those for themselves. What I really loved, though, was the continued exploration of Minare’s personality. For example, when she has the jitters and receives reassurance, she cries, “I can feel it rushing back! My usual baseless, overflowing confidence!” She might have come off as an unsympathetic and abrasive character, but that line shows that she’s fully aware of her flaws. Later, after a brief (and awesome) reunion with Mitsuo, she displays a knack for more self-analysis, reflecting that while she usually doesn’t take shit from anyone, she has a certain weakness for pathetic guys who need someone to dote over them. I expect that this capacity for reflection will allow her to make the most of the opportunity she’s been given.

Volume two is where things really get great. Mato has inventive ideas for Minare’s show, and I think I will let readers discover those for themselves. What I really loved, though, was the continued exploration of Minare’s personality. For example, when she has the jitters and receives reassurance, she cries, “I can feel it rushing back! My usual baseless, overflowing confidence!” She might have come off as an unsympathetic and abrasive character, but that line shows that she’s fully aware of her flaws. Later, after a brief (and awesome) reunion with Mitsuo, she displays a knack for more self-analysis, reflecting that while she usually doesn’t take shit from anyone, she has a certain weakness for pathetic guys who need someone to dote over them. I expect that this capacity for reflection will allow her to make the most of the opportunity she’s been given. Widowed math teacher Kohei Inuzuka wants to do his best when it comes to raising his daughter, Tsumugi. It’s been six months since his wife passed away, and because he has never had much of an appetite and hasn’t fared well with cooking in the past, he mostly relies on store-bought fare for Tsumugi. However, after they run into one of his students, Kotori Iida, while looking at cherry blossoms, he can’t help but notice how fascinated Tsumugi is by the home-cooked lunch Kotori’s been eating. To make his daughter happy, he ends up taking her to Kotori’s family restaurant, which leads to regular dinner parties where they experiment with making different things together.

Widowed math teacher Kohei Inuzuka wants to do his best when it comes to raising his daughter, Tsumugi. It’s been six months since his wife passed away, and because he has never had much of an appetite and hasn’t fared well with cooking in the past, he mostly relies on store-bought fare for Tsumugi. However, after they run into one of his students, Kotori Iida, while looking at cherry blossoms, he can’t help but notice how fascinated Tsumugi is by the home-cooked lunch Kotori’s been eating. To make his daughter happy, he ends up taking her to Kotori’s family restaurant, which leads to regular dinner parties where they experiment with making different things together. chawanmushi, and some seriously drool-inducing gyoza. Recipes are included, and for the first time, I feel like they’re actually something I might attempt.

chawanmushi, and some seriously drool-inducing gyoza. Recipes are included, and for the first time, I feel like they’re actually something I might attempt. He and Kotori maintain their distance at school, and he frequently worries about inconveniencing her mother. And yet, the gatherings make Tsumugi so happy—and even lift her spirits when she begins to truly comprehend the permanence of her mother’s absence—that he gratefully accepts the Iidas’ hospitality. He behaves professionally at all times. Kotori, however, seems to be developing feelings for him, though it’s all mixed up as she sees him as both a guy and as a father figure. I wouldn’t be surprised if the manga ends with them getting married, but I hope nothing romantic ensues for a very long time.

He and Kotori maintain their distance at school, and he frequently worries about inconveniencing her mother. And yet, the gatherings make Tsumugi so happy—and even lift her spirits when she begins to truly comprehend the permanence of her mother’s absence—that he gratefully accepts the Iidas’ hospitality. He behaves professionally at all times. Kotori, however, seems to be developing feelings for him, though it’s all mixed up as she sees him as both a guy and as a father figure. I wouldn’t be surprised if the manga ends with them getting married, but I hope nothing romantic ensues for a very long time.