The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

From the star.

From the stars.

The sea is the mother.

The people are the breasts

Heaven is the playground.

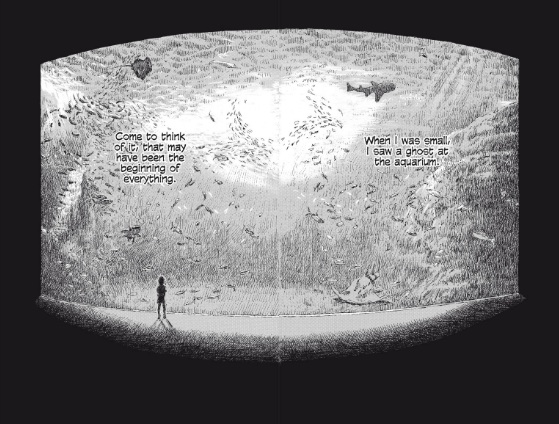

How, exactly, sea and sky are connected is the central mystery of Children of the Sea. The story begins in the present day, as a woman promises to tell her son “about a giant shark that lives deep beneath the waves,” “the ghosts that cross the sea,” and “the path that connects the sea to space.” We then jump back to a defining moment in Ruka’s childhood when, on a visit to the local aquarium, she saw a fish disappear in a bright flash of light – what she describes as “a ghost in the water.” Ruka doesn’t think much of the incident until she meets Umi and Sora, two humans whose bodies are better adapted to life in the ocean than on land. Under the watchful eye of her father and his assistant Jim, the boys live at the aquarium, venturing out into daylight only to visit the hospital and swim in the open ocean. Eager to know more about Umi and Sora, Ruka sets out to sea with them, where she watches the boys swim with a second “ghost in the water”: a luminescent whale shark that leaves a starry wake in its trail.

…

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,  Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished.

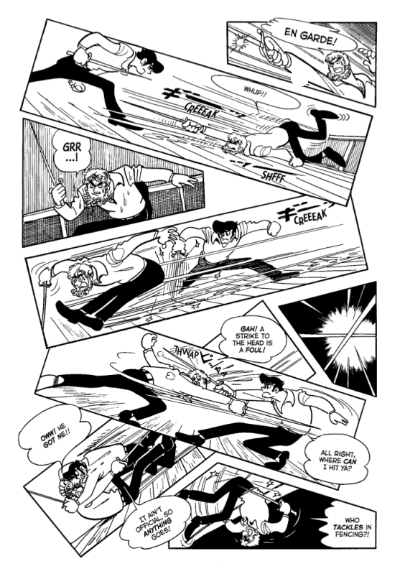

Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished. For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear.

For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear. Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.”

Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.” When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century.

When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century. Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

Dangerous Minds, Dead Poets Society, Stand and Deliver, and To Sir, With Love all depict teachers who are heroic in their self-sacrifice, renouncing money, family ties, and even their reputations in order to inspire students. Kojiro Ishido, the anti-hero of Bamboo Blade, won’t be mistaken for any of these noble educators. He’s bankrupt, morally and financially, and so eager to dig himself out of debt that he’d exploit his students in a heartbeat.

Dangerous Minds, Dead Poets Society, Stand and Deliver, and To Sir, With Love all depict teachers who are heroic in their self-sacrifice, renouncing money, family ties, and even their reputations in order to inspire students. Kojiro Ishido, the anti-hero of Bamboo Blade, won’t be mistaken for any of these noble educators. He’s bankrupt, morally and financially, and so eager to dig himself out of debt that he’d exploit his students in a heartbeat.

Though its name evokes images of the White House — and maybe even the unctuous Josiah Bartlett — The History of the West Wing is, in fact, an adaptation of a twelfth-century play by the Moliere of China, Wang Shifu.

Though its name evokes images of the White House — and maybe even the unctuous Josiah Bartlett — The History of the West Wing is, in fact, an adaptation of a twelfth-century play by the Moliere of China, Wang Shifu.

The year is 1955. Twenty-year-old Masayo, an aspiring painter from Hakodate, apprentices herself to Goro Kawabuko, a handsome widower who teaches at a Tokyo art college. In exchange for a weekly lesson, Masayo agrees to keep house for Goro and tutor his daughter Momoko, a strange, withdrawn child whose only companion is a regal white cat named Lala.

The year is 1955. Twenty-year-old Masayo, an aspiring painter from Hakodate, apprentices herself to Goro Kawabuko, a handsome widower who teaches at a Tokyo art college. In exchange for a weekly lesson, Masayo agrees to keep house for Goro and tutor his daughter Momoko, a strange, withdrawn child whose only companion is a regal white cat named Lala.