The Count of Monte Cristo, arguably Alexander Dumas’ best novel, is a big, sprawling beast, stuffed to the gills with characters, subplots, secret identities, suicides, and dramatic confrontations; small wonder that GONZO felt it would provide a solid foundation for a twenty-four episode anime. The series debuted to critical acclaim in 2004, thanks largely to its arresting visuals (designer Anna Sui had a hand in creating the characters’ elaborate costumes) and its dramatic soundtrack, which employed key musical themes from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (the gold standard for operatic madness scenes) and Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony (a piece of program music inspired by Byron’s poem of the same name).

…

If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life.

If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life. 10. ASTRAL PROJECT

10. ASTRAL PROJECT 9. CHIKYU MISAKI

9. CHIKYU MISAKI 8. THE NAME OF THE FLOWER

8. THE NAME OF THE FLOWER 7. SHIRLEY

7. SHIRLEY 6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS

6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS 5. PRESENTS

5. PRESENTS 4. GON

4. GON 3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE

3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE 2. SWAN

2. SWAN 1. EMMA

1. EMMA 10. Astral Project

10. Astral Project 9. Chikyu Misaki

9. Chikyu Misaki 8. The Name of the Flower

8. The Name of the Flower 7. Shirley

7. Shirley 6. Kiichi and the Magic Books

6. Kiichi and the Magic Books 5. Presents

5. Presents 4. Gon

4. Gon 3. From Eroica with Love

3. From Eroica with Love 2. Swan

2. Swan 1. Emma

1. Emma I like science fiction, I really do, but I have limited tolerance for certain tropes: futures in which all the women dress like strippers — or worse, fascist strippers — futures in which giant bugs menace Earth, and futures in which magic and technology freely commingle. Small wonder, then, that Kia Asamiya’s Silent Möbius has never been on my short list of must-read manga — it’s a festival of cheesecake, gooey monsters, and pistol-packing soldiers who, in a pinch, must decide whether to cast a spell or fire a rocket launcher at the enemy. Imagine my surprise when I discovered just how entertaining Silent Möbius turned out to be, gratuitous panty shots, bugs, and all.

I like science fiction, I really do, but I have limited tolerance for certain tropes: futures in which all the women dress like strippers — or worse, fascist strippers — futures in which giant bugs menace Earth, and futures in which magic and technology freely commingle. Small wonder, then, that Kia Asamiya’s Silent Möbius has never been on my short list of must-read manga — it’s a festival of cheesecake, gooey monsters, and pistol-packing soldiers who, in a pinch, must decide whether to cast a spell or fire a rocket launcher at the enemy. Imagine my surprise when I discovered just how entertaining Silent Möbius turned out to be, gratuitous panty shots, bugs, and all. Like Water for Kimchi — that’s how I would describe 13th Boy, a weird, wonderful Korean comedy with a strong element of magical realism.

Like Water for Kimchi — that’s how I would describe 13th Boy, a weird, wonderful Korean comedy with a strong element of magical realism.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

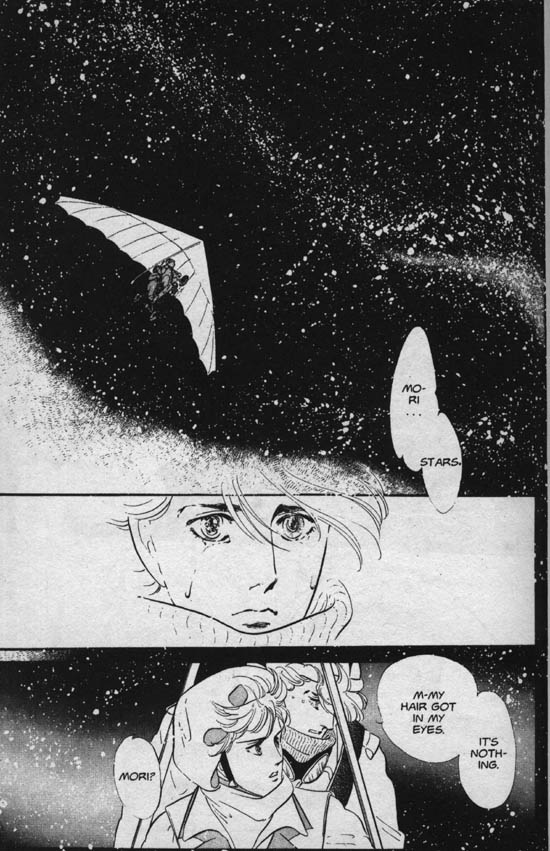

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN