When I tell people that I review manga, they often ask me, “Isn’t it all porn and ninjas?” No, I assure them, there are manga about cooking, gambling, dating, teaching, crime solving, alien fighting, computer programming, ghost busting, mind reading, wine tasting, dog training, and just about any other topic you can imagine; if there’s an audience to be served, Japanese publishers will find a way to reach them through comics. “But it seems like every manga I’ve seen has a girl in a short skirt waving a sword,” they reply. I usually offer a counter-example — say, Ouran High School Host Club or What’s Michael? — but I know the kind of manga they have in mind. It’s filled with female characters who have women’s bodies and girls’ faces; schoolgirls who wear their uniforms twenty-four hours a day; fighters who use swords, even though the story is set in the present; and supporting characters who dress like Edo-era refugees, even though their cohorts are wearing sneakers and hoodies. In short, what they’re seeing in their mind’s eye looks a lot like Tenjo Tenge.

Plot-wise, Tenjo Tenge isn’t much more complicated than “girls in skirts waving katanas.” The story takes place at Todo Academy, one of those only-in-manga institutions where students study martial arts technique to the exclusion of anything else. (If anyone attends a math class in Tenjo Tenge, I missed it.) First-year students Soichiro Nagi and Bob Makihara fully expect to rule the roost with their awesome fighting skills, but are quickly disabused of the notion when they run afoul of Todo’s Executive Council. Mindful of their greenhorn status, the boys join the Juken Club, an organization lead by Maya Natsume, a third-year student who’s handy with a sword. In so doing, however, Soichiro and Bob become targets for the Executive Council, which carries on an energetic, bloody feud with Maya and her younger sister.

Flipping through the first volume of VIZ’s “Full Contact” edition, it’s easy to see why DC Comics censored the original English print run. The story abounds in the kind of gratuitous nudity and sexual encounters that make an unadulterated version a tough sell at big chain stores like Wal-Mart and Barnes & Noble. DC Comics’ solution was an inelegant one: they re-wrote the script, drew bras and panties on naked girls, and cut some of the most offensive passages. As an advocate of free speech, I can’t condone the bowdlerization of any text, especially in the interest of a more commercially viable age-rating , but as a woman, it’s hard to celebrate the restoration of a graphic rape scene or images of naked girls throwing themselves at the heroes.

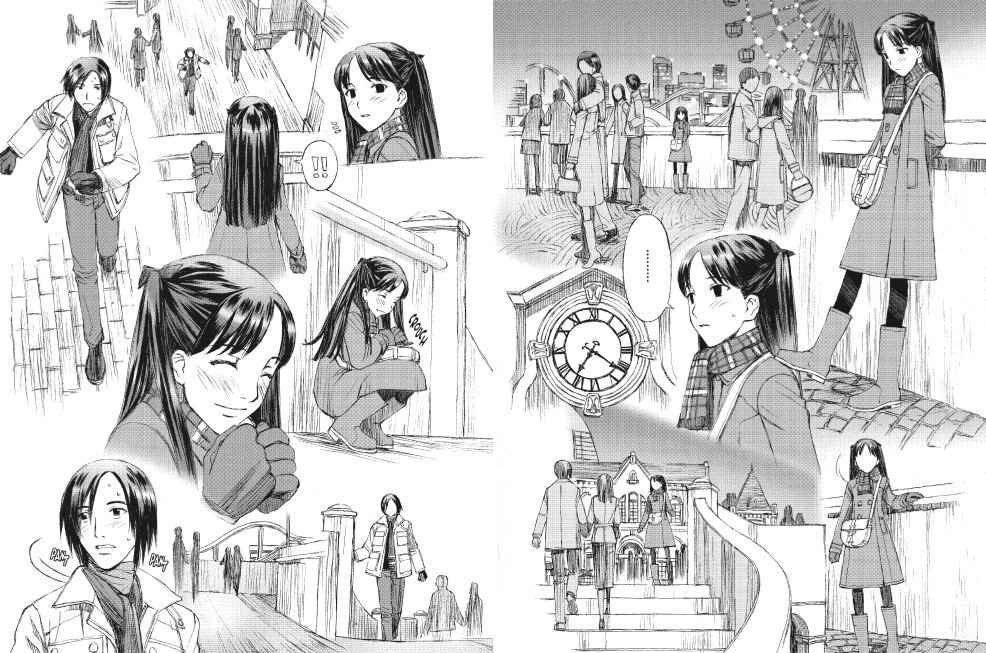

Whether those scenes are really necessary to advancing the plot is another issue. The rape, in particular, is an ugly exercise in exploitation, pitting a grown man against a teenager who has a twelve-year-old’s face and a porn star’s body. Though Oh!Great shows us the victim’s terrified expression in several panels, he lavishes far more attention on her anatomy, twisting her body into the kind of grotesque, provocative poses that were a stock-in-trade of Hustler. What makes this passage especially nasty is its underlying intent; we’re not being asked to identify with the victim, or burn with outrage over her violation, but to be aroused by her naked body. In a word: yuck.

From time to time, Oh!Great gives the Natsume sisters a chance to strut their martial arts stuff, suggesting that both girls are as tough and cunning as their male counterparts, but he can’t resist tearing off their clothes, or showing us their panties, especially when they’re in the middle of intense, hand-to-hand combat. And if the characters’ complete objectification wasn’t bad enough, Oh!Great draws such grossly misshapen bodies that it’s hard to imagine who would find them sexy; say what you will about Ryoichi Ikeda and Kazuo Koike’s Wounded Man — and yes, there’s plenty to say about the exploitation of its female characters — but Ikeda knew how to draw beautiful women. Oh!Great’s female characters, on the other hand, look like blow-up dolls, incapable of standing on their own two feet, let alone brandishing a sword or high-kicking an opponent.

Tenjo Tenge fans who were angered by the first English-language edition will be pleased with VIZ’s new translation. Many of the elements that had been eliminated or camouflaged in the first version have been restored; characters drop f-bombs and drop trou without editorial intervention. As an added enticement, VIZ has formatted the story as a series of two-in-one omnibuses, complete with glossy color plates and oversized trim. Given the care with which the new Tenjo Tenge was prepared, I wish I could say that the uncensored version convinced me that I’d unfairly dismissed the genius of Oh!Great the first time around. Alas, the answer is no; the story comes is too perilously close to the porn-and-ninjas stereotype for my taste.

Review copy provided by VIZ Media, LLC. Volume one of Tenjo Tenge will be released on June 7, 2011.

TENJO TENGE: FULL CONTACT EDITION, VOL. 1 • BY OH!GREAT • VIZ MEDIA • 386 pp. • RATING: MATURE (18+)