In the interests of improving my blogroll, what are some of your favorite comics or pop culture blogs that I haven’t already linked? It seems greedy to ask for more great reading, but… well… I am greedy.

Features & Reviews

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight 5 by Jane Espenson, et al.: C+

From the back cover:

From the back cover:

When Buffy’s former classmate-turned-vampire Harmony Kendall lands her own reality TV show, vampires are bolstered into the mainstream. Humans fall in line; they want a piece of the glitz, glam, and eternal youth bestowed upon these mysterious creatures of the night. What’s a Slayer to do when vampires are the trendiest thing in the world? While humans donate their blood to the vampire cause, Slayers—through a series of missteps, misfortunes, and anti-Slayer propaganda driven by the mysterious Twilight—are forced into hiding.

Review:

The fifth collected volume of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight comics is comprised of five one-shots, four of which are written by writers from the show. You might think that’s a good thing, but it doesn’t always turn out to be the case.

Issue 21, “Harmonic Divergence,” is written by Jane Espenson. Captured on film one evening while snacking on Andy Dick, Harmony becomes an instant celebrity. A reality show—with Clem for a sidekick!—on MTV follows. The show portrays Harmony sympathetically, as someone who drinks from humans but doesn’t do them any harm, and when a Slayer decides to take Harmony out on-camera, it spawns a tide of anti-Slayer sentiment.

It’s true, vampires are a big craze at the moment, but I find this whole plotline—it continues for some time—to be kind of stupid. What’s worse is that George Jeanty seriously can’t draw Mercedes McNab (the actress who portrays Harmony) to save his life. He does no better with original characters, either. At one point the nameless Slayer looks like a middle-aged man in drag.

It’s true, vampires are a big craze at the moment, but I find this whole plotline—it continues for some time—to be kind of stupid. What’s worse is that George Jeanty seriously can’t draw Mercedes McNab (the actress who portrays Harmony) to save his life. He does no better with original characters, either. At one point the nameless Slayer looks like a middle-aged man in drag.

Issue 22, “Swell,” is not much better. Written by Steven S. DeKnight, it takes place in Tokyo, where Kennedy has arrived to conduct an evaluation of newly promoted Satsu. Meanwhile, Twilight, the big bad of the season, has taken over the San(to)rio Corporation and disguised a bunch of demons as “Vampy Cat” plushies with plans to ship them to Scotland, where Buffy is. Probably this is supposed to be funny, but again, it’s just kind of stupid. Kennedy does offer Satsu some advice about pining for a straight girl, though, and the issue ends with Satsu resolved to move on.

The best story of the lot is “Predators and Prey,” by Drew Z. Greenberg. Taking advantage of the current attitude towards Slayers, rogue Slayer Simone and her gang have ousted the residents of an Italian village and taken over. Feeling responsible as Simone’s former Watcher, Andrew has taken an “ends justify the means” approach to getting intel on her whereabouts, resulting in not only an amusing roadtrip with Buffy, but a lot of growth for his character. Having never earned anyone’s trust before, he’s terrified of losing it, which makes him screw up for the right reasons. Buffy tells him to get used to it, because that’s her family’s specialty. Not only does this issue have some funny lines, it’s actually quite significant for Andrew. Gold star for Greenberg!

The one story penned by someone who never wrote for the show is “Safe,” by Jim Krueger. It stars Faith and Giles, which it earns points for immediately, as they investigate a so-called Slayer Sanctuary for girls who decide they’d rather not fight. The plot is kind of lame, but there’s some good dialogue, particularly from Faith, and some insights into her deep feelings of regret for her early failings as a Slayer. This issue is drawn by Cliff Richards, who does a much better job than Jeanty at capturing the likenesses of the actors. He also seems to have a greater repertoire of facial expressions.

The one story penned by someone who never wrote for the show is “Safe,” by Jim Krueger. It stars Faith and Giles, which it earns points for immediately, as they investigate a so-called Slayer Sanctuary for girls who decide they’d rather not fight. The plot is kind of lame, but there’s some good dialogue, particularly from Faith, and some insights into her deep feelings of regret for her early failings as a Slayer. This issue is drawn by Cliff Richards, who does a much better job than Jeanty at capturing the likenesses of the actors. He also seems to have a greater repertoire of facial expressions.

Lastly, issue 25 is called “Living Doll” and is written by Doug Petrie. Dawn has gone missing and Buffy and Xander follow her hoofprinty trail while Andrew tracks down Kenny, the guy responsible for casting the spell on her in the first place. Long story short, Dawn apologizes to Kenny, becomes human again, and spends some quality time with Buffy watching Veronica Mars. (Man, I miss that show.)

While the first two stories are pretty bad, the other three offer solid character moments even though the plots themselves leave something to be desired. I’ve said before that this is something a Buffy fan simply becomes used to, so it doesn’t bother me all that much. I’d probably be happier with a series full of vignettes like these than what is coming over the next couple of arcs.

Follow Friday: The localizers

Server outages and related angst have given us a a rough week at Manga Bookshelf, so today seems quite an appropriate time to spread a little goodwill over the manga industry twitterverse.

Server outages and related angst have given us a a rough week at Manga Bookshelf, so today seems quite an appropriate time to spread a little goodwill over the manga industry twitterverse.

One of the things I’ve loved about Twitter, is that it’s given me the opportunity to interact with the people who make it possible for me to actually read manga. I’m referring, of course, to the localizers–the translators, adapters, and editors whose work I rely on to enjoy manga in English to the greatest extent possible.

Twitter is teeming with manga industry folks, and though I can’t possibly list them all here, I’ll pick out a few I’ve especially enjoyed.

William Flanagan is not only one of my favorite translators around, he’s also a great conversationalist and one of my favorite twitterers. You can also find twin translators Alethea & Athena Nibley lurking around the twitterverse.

Adaptor Ysabet Reinhardt MacFarlane brings a smart, thoughtful presence to the discussion.

And for a look into the world of manga editing, don’t miss the Twitter feeds of Asako Suzuki, Nancy Thistlethwaite, and Daniella Orihuela-Gruber.

This is merely a handful, of course–just a peek into the riches Twitter has to offer. Who are your favorite manga localizers to follow?

License Request Day: More Yumi Unita

I’m quite delighted that so many people seem to like Yumi Unita’s excellent Bunny Drop (Yen Press). I have no idea if critical approval has translated into solid sales, or even solid sales by the standards of the often struggling josei category. I just know that it makes me happy when people like things that I think are good.

And I can’t help but suspect that Unita has something to do with the fact that Bunny Drop is so good. Call me crazy, but I think there’s causality there. So in the interest of making myself even happier, and assuming that Unita may be able to contribute to this process, I thought I’d see what other works were waiting in the wings.

One of her earliest ongoing series looks a little bizarre. It’s the single-volume Sukimasuki, and it ran in Shogakukan’s IKKI. It’s apparently about romantic complications between a pair of voyeurs. Of course it’s been published in Italian, under the title Guardami by Kappa Edizioni. Its IKKI provenance is the strongest thing in this title’s favor, so I’ll refrain from any serious wheedling until someone persuades me that it’s fully necessary.

One of her earliest ongoing series looks a little bizarre. It’s the single-volume Sukimasuki, and it ran in Shogakukan’s IKKI. It’s apparently about romantic complications between a pair of voyeurs. Of course it’s been published in Italian, under the title Guardami by Kappa Edizioni. Its IKKI provenance is the strongest thing in this title’s favor, so I’ll refrain from any serious wheedling until someone persuades me that it’s fully necessary.

Still in the seinen vein but more domestic-sounding (and looking) is Yoningurashi, which was serialized in Takeshobo’s Manga Life Original. Pleased as I am with Unita’s handling of an adoptive family, I would certainly be open to her take on another variation on the family theme. Plus, that cover is really adorable, isn’t it? I’m not entirely certain, but I think this one’s a four-panel comic strip, given that most of the series in Manga Life seem to be in that format. But it’s not about a group of four or more schoolgirls, so I’m a little confused.

Still in the seinen vein but more domestic-sounding (and looking) is Yoningurashi, which was serialized in Takeshobo’s Manga Life Original. Pleased as I am with Unita’s handling of an adoptive family, I would certainly be open to her take on another variation on the family theme. Plus, that cover is really adorable, isn’t it? I’m not entirely certain, but I think this one’s a four-panel comic strip, given that most of the series in Manga Life seem to be in that format. But it’s not about a group of four or more schoolgirls, so I’m a little confused.

Update: Alexander (Manga Widget) Hoffman informs me that this title isn’t four-panel after all, though it’s reassuring to see that Unita is still having some of her characters rock a pair of bell-bottomed trousers.

Can I be finished catering to the seinen demographic? Unita’s got a ton of josei under her belt. One of her current series is called Nomino, and it runs in Hakusensha’s new-ish josei magazine, Rakuen le Paradis. Erica (Okazu) Friedman speaks very highly of Rakuen le Paradis, and I yearn to learn to love Hakusensha josei as much as I love Hakusensha shôjo, which is the best shôjo there is. Getting back to Rakuen, it looks like it covers some impressive territory, at least in terms of sexual orientation of its stories’ protagonists and probably in terms of tone. And they managed to lure Kio (Genshiken) Shimoku to draw something for them. And, while this says nothing about the magazine’s quality, its name reminds me of seminal Styx hit “Rockin’ the Paradise” from their hit album, Paradise Theatre, which was the album of choice for my circle of friends in high school. It was the album boys and girls could agree on without reservation or compromise. If the tension over the Air Supply party soundtrack got too acrimonious, Styx was always there to offer the right balance of driving and swoony to make everyone happy, or at least not grumpy.

Can I be finished catering to the seinen demographic? Unita’s got a ton of josei under her belt. One of her current series is called Nomino, and it runs in Hakusensha’s new-ish josei magazine, Rakuen le Paradis. Erica (Okazu) Friedman speaks very highly of Rakuen le Paradis, and I yearn to learn to love Hakusensha josei as much as I love Hakusensha shôjo, which is the best shôjo there is. Getting back to Rakuen, it looks like it covers some impressive territory, at least in terms of sexual orientation of its stories’ protagonists and probably in terms of tone. And they managed to lure Kio (Genshiken) Shimoku to draw something for them. And, while this says nothing about the magazine’s quality, its name reminds me of seminal Styx hit “Rockin’ the Paradise” from their hit album, Paradise Theatre, which was the album of choice for my circle of friends in high school. It was the album boys and girls could agree on without reservation or compromise. If the tension over the Air Supply party soundtrack got too acrimonious, Styx was always there to offer the right balance of driving and swoony to make everyone happy, or at least not grumpy.

Oh, and Nomino is a slice-of-life story about the friendship between a boy and girl, or something. Maybe they’d both like Styx! Or something. I don’t care. It’s Unita, and it comes from a cool-sounding magazine for grown women. Hook, line, want.

Okay, so that’s three varied, perfectly respectable choices for publishers who are willing to feed my Unita habit. She seems like one of those impressively versatile creators who draws for a variety of audiences, and even in different formats if my four-panel theory is correct. I would like for someone to try and give her the Natsume Ono treatment and publish lots of different works from her catalog.

Manga Artifacts: Hotel Harbour View

Back in 1990, before anyone had hit on the magic formula for selling manga to American readers, VIZ tried a bold experiment. They released a handful of titles in a prestige format with fancy covers, high-quality paper, and a large trim size, and called them “Viz Spectrum Editions.” Only three manga got the Viz Spectrum treatment: Yu Kinutani’s Shion: Blade of the Minstrel, Yukinobu Hoshino’s Saber Tiger, and Natsuo Sekikawa and Jiro Taniguchi’s Hotel Harbour View. While neither the imprint nor the format survived, these three titles helped pave the way for VIZ’s later efforts to establish its Signature line.

Hotel Harbour View, by far the strongest of the three, is a stylish foray into hard-boiled crime fiction. In the title story, a man patronizes a once-elegant bar in Hong Kong, telling the bartender that he’s waiting for the person who’s supposed to kill him, while in the second story, “A Brief Encounter,” an assassin returns to Paris, where his former associates — including his protege — lie in wait for him.

As editor Fred Burke observes in his afterword, both stories are as much about style and genre as they are about exploring what motivates people to kill. The characters in both stories are deeply concerned with scripting their own lives, of behaving the way hit men and high-class call girls do in the movies. None of them wear simple street clothes; all of them are in costume, wearing gloves and suits and garter belts. (In one scene, for example, an assassin asks a bystander to hand him his hat, even though he lies dying in a pool of blood. “Just don’t feel right without it,” he explains.) Their words, too, are carefully chosen; every conversation has the kind of pointed quality of a Dashiell Hammett script, with characters trading quips and telling well-rehearsed stories about their past. A brief surveillance operation, for example, yields this tersely wonderful exchange between two female assassins:

“She’s French, isn’t she? Parisienne.”

“How can you tell?”

“She looks arrogant and stubborn. The sort who ruins men.”

“He loves her. That’s why he came back to Paris.”

“And how can you tell?”

“I’m a Parisienne, too.”

[As an aside, I should note that Gerard Jones and Matt Thorn’s excellent translation brings Sekikawa’s script to life in English; each character has a distinctive voice, and the dialogue is thoroughly idiomatic.]

The violence has a cinematic flavor as well; Taniguchi’s balletic gunfights call to mind the kind of technically dazzling shoot-outs that became a staple of John Woo’s filmmaking in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Taniguchi uses many of the same tricks. He follows a bullet’s trajectory from the gun barrel to its point of impact, showing us the victim’s terrified face as the bullet closes in on its target; stages elaborate duels in which passing trains demand split-second timing from the well-armed participants; and shows us a hit gone bad from dozens of different angles. In one the book’s most stylish sequences, we see a gunman’s reflection in a shattered mirror; as the “camera” pulls back from that initial image, we realize that we’re seeing things from the killer’s point of view, not the gunman’s. A dramatic cascade of glass destroys his reflection as he slumps to the floor — a perfect movie ending for a character obsessed with orchestrating his own death.

Like Taniguchi’s other work, there’s a slightly stiff quality to the artwork. His characters are drawn with meticulous attention to detail, yet their faces remain impassive even when bullets fly and old lovers betray them. That detachment can be frustrating in other contexts, but in Hotel Harbour View it registers as sang-froid; the characters’ composure is as essential to their performances as their costumes and studied banter, as each self-consciously fulfills their role in the drama.

Though Hotel Harbour View is out of print, copies are still widely available through online retailers; I ordered mine directly from Amazon. You’ll also find a robust market for second-hand copies; expect to pay between $4.00 and $20.00 for a copy in good to excellent condition.

Manga Artifacts is a monthly feature exploring older, out-of-print manga published in the 1980s and 1990s. For a fuller description of the series’ purpose, see the inaugural column.

HOTEL HARBOUR VIEW • SCRIPT BY NATSUO SEKIKAWA, ART BY JIRO TANIGUCHI • VIZ MEDIA • 94 pp. • RATING: MATURE (18+)

3 Things Thursday: Second Chances

I’m a very patient reader. I like long manga series, and since the long ones usually pace themselves (up to three full volumes of exposition at times), I’ll usually give a series that’s captured the slightest of my interest at least five volumes to woo me. Some of my very favorite series took a while to warm up for me, including the likes of xxxHolic and Fullmetal Alchemist–series I now vigorously recommend.

While it’s rare that I’ll drop a series completely before the five volume mark, there are times when I simply can’t go on. Sometimes I can recognize this as a pure matter of taste. Toriko, for instance, is a perfectly fine series… if only it didn’t make me recoil in disgust. Others, I find genuinely offensive or perhaps just completely lacking.

Considering my overall patience, I usually trust myself on these few occasions, but there are times when my judgement is so at odds with those whose tastes I normally share, re-evaluation seems in order. So for today’s 3 Things I’ll ponder a few rejected series that have earned a second look.

3 manga series that deserve a second chance:

1. Butterflies, Flowers | Yuki Yoshihara | Viz Media – Though this series’ first volume won my praise immediately, its second and third volumes so rubbed me the wrong way that despite my claim that the humor would keep me going, I privately doubted I’d ever pick it up again. A quote, “It’s possible I’m still holding a grudge over “strict but warm,” which ranks right up there with “I get the message” and “Men have dreams that women will never be able to understand” on my list of Great Moments in Imported Sexism.”

1. Butterflies, Flowers | Yuki Yoshihara | Viz Media – Though this series’ first volume won my praise immediately, its second and third volumes so rubbed me the wrong way that despite my claim that the humor would keep me going, I privately doubted I’d ever pick it up again. A quote, “It’s possible I’m still holding a grudge over “strict but warm,” which ranks right up there with “I get the message” and “Men have dreams that women will never be able to understand” on my list of Great Moments in Imported Sexism.”

But when a series is consistently championed by the likes of David Welsh, it’s time to step back and figure out where the hell I went wrong. Butterflies, Flowers, we’ll meet again soon.

2. Black Butler | Yana Toboso | Yen Press – I tried to be fair to the first two volumes, I really did. I pointed out some character bits I genuinely liked–noted how there might be a deeper story hidden under the glitz. But these lines really get to the heart of my problems with the series, “That these series are intended to appeal to female readers seems plain, with their bishonen character designs, elaborate costuming, and frequent BL overtones. Unfortunately, Black Butler‘s specialty is not just BL but shota, which makes Sebastian even creepier and not at all in a good way … Black Butler gets off to a very slow and fairly vapid start…”

2. Black Butler | Yana Toboso | Yen Press – I tried to be fair to the first two volumes, I really did. I pointed out some character bits I genuinely liked–noted how there might be a deeper story hidden under the glitz. But these lines really get to the heart of my problems with the series, “That these series are intended to appeal to female readers seems plain, with their bishonen character designs, elaborate costuming, and frequent BL overtones. Unfortunately, Black Butler‘s specialty is not just BL but shota, which makes Sebastian even creepier and not at all in a good way … Black Butler gets off to a very slow and fairly vapid start…”

Yet, just last night, Michelle Smith gave me reason to give the series another chance. What Michelle says, goes. It’s that simple.

3. Little Butterfly | Hinako Takanaga | DMP – This one is a long time coming, and while it’s a series I’ve actually read in its entirety, my initial dismissal of it is sufficient for it to qualify. Way back in my infamous thoughts on yaoi (which I’m now afraid to re-read), I said of Little Butterfly that maybe if it “had actually been ten volumes, and the romance was developed over the course of a much greater plot, I would have actually liked (it), because honestly I did find the characters interesting, what I got to see of them. I just felt cheated by the way the ‘plot’ and the relationships were rushed along to serve the romance.”

3. Little Butterfly | Hinako Takanaga | DMP – This one is a long time coming, and while it’s a series I’ve actually read in its entirety, my initial dismissal of it is sufficient for it to qualify. Way back in my infamous thoughts on yaoi (which I’m now afraid to re-read), I said of Little Butterfly that maybe if it “had actually been ten volumes, and the romance was developed over the course of a much greater plot, I would have actually liked (it), because honestly I did find the characters interesting, what I got to see of them. I just felt cheated by the way the ‘plot’ and the relationships were rushed along to serve the romance.”

But when someone like Kate Dacey gives it a review like this… what’s a girl to do? I actually have Kate’s omnibus sitting here in my living room, and it’s high time I gave it that second look.

Series that didn’t make the cut, but could have include St. Dragon Girl (beloved by Ed Sizemore) and Hot Gimmick (secretly loved by… everyone). So, readers, what series should you give a second chance?

Ashenden by W. Somerset Maugham: A

Book description:

Book description:

When war broke out in 1914, Somerset Maugham was dispatched by the British Secret Service to Switzerland under the guise of completing a play. Multilingual, knowledgeable about many European countries and a celebrated writer, Maugham had the perfect cover, and the assignment appealed to his love of romance, and of the ridiculous. The stories collected in Ashenden are rooted in Maugham’s own experiences as an agent, reflecting the ruthlessness and brutality of espionage, its intrigue and treachery, as well as its absurdity.

Review:

I have only read two books by W. Somerset Maugham, of which this is the second, and I can already proclaim without a shred of doubt that he’s one of my favorite writers. Everything about the way he writes appeals to me. He’s wry and keenly observant, with a knack for creating vivid portraits of his characters while wasting not a single word.

Here’s an example, taken from the story “A Chance Acquaintance.”

Mr. Harrington was devoted to his wife and he told Ashenden at unbelievable length how cultivated and what a perfect mother she was. She had delicate health and had undergone a great number of operations, all of which he described in detail. He had had two operations himself, one of his tonsils and one to remove his appendix, and he took Ashenden day by day through his experiences. All his friends had had operations and his knowledge of surgery was encyclopedic. He had two sons, both at school, and he was seriously considering whether he would not be well-advised to have them operated on.

Maugham’s writing is so wonderful that if I learned he’d penned a six-volume ode to cole slaw, I would grab it because I could be certain that it would be witty and somehow make me think of cole slaw in a way I never had before. The fact that the stories in Ashenden are actually excellent, therefore, is just icing on the proverbial cake.

Instead of being utterly disconnected, the stories here function as a string of vignettes in the life of Ashenden, a writer who’s been drafted as an agent of the British Intelligence Department during World War I. They’re at least partly based on Maugham’s own experiences in this capacity, though he hastens to impress upon the reader that this is a work of fiction.

Ashenden is recruited by a Colonel known to him only as R., and sent on a variety of missions that include playing escort to an eccentric Mexican assassin, arranging for a traveling dancer to betray her revolutionary Indian lover, ascertaining whether an Englishman spying for Germany might be recruited as a double agent, attempting to prevent the Bolshevik revolution, and more. Sometimes he succeeds, frequently with bittersweet results, and sometimes he fails. Occasionally his objective or the outcome is not known to the reader, since Maugham is more interested in describing the people Ashenden meets than in the specifics of his efforts.

It’s impossible to pick a favorite story, as each has its share of indelible moments to recommend it. Since the tales featuring the voluble Mr. Harrington are at the end of the collection and I have read them most recently, I feel a soft spot for those in particular, though “The Traitor” and “Giulia Lazzari” are each unforgettable.

If you’ve a particular interest in war-time Europe, Ashenden ought not be missed. Really, it ought not be missed in any case, but if the subject matter holds special appeal for you then you’ve really got no excuse!

From the stack: The Secret Notes of Lady Kanoko

The world isn’t populated exclusively with loving optimists, so it’s only appropriate that the world of shôjo manga occasionally reflects that. The surly and the cynical, it seems, can be as worthy of the spotlight as the open-hearted and the gracious, at least in Ririko Tsujita’s The Secret Notes of Lady Kanoko (Tokyopop).

The world isn’t populated exclusively with loving optimists, so it’s only appropriate that the world of shôjo manga occasionally reflects that. The surly and the cynical, it seems, can be as worthy of the spotlight as the open-hearted and the gracious, at least in Ririko Tsujita’s The Secret Notes of Lady Kanoko (Tokyopop).

The titular lady, junior high student Kanoko Naeoko, is rather like animated MTV legend Daria in that she’d rather observe human behavior than engage with actual humans. Kanoko is also like Daria in that she finds herself dragged into the woes and schemes of her classmates, whether she likes it or not. Since Kanoko is generally the smartest person in the room, you can see why she’s a go-to resource when things get tricky.

And things do get tricky. Kanoko has standards for her eavesdropping, naturally fixating on the juicier specimens — the hypocrites, the schemers, the egotists. As much as Kanoko objects to interpersonal connection, she seems to appreciate a challenge, and guiding these fools out of their misfortunes provides that.

In a more average comic, it might be safe to assume that she’s really a softy under her isolating exterior, but really, she’s not. That’s what’s pretty great about her. There are a few people that she genuinely likes, but she’s sincere in her general indifference. It isn’t a defense, except in the way that she’s protecting herself from… well… catching stupidity or dullness.

Tsujita plays around with shôjo tropes in her storytelling. There’s the plain girl oppressed by her prettier classmate, except the plain girl is flat-out nuts, and she’s as prone to bullying as her rival. There’s the girl with big dreams who’s actually an obnoxious narcissist with self-confidence so impenetrable as to have possible military applications. There are bratty students and awful teachers at every turn, and Kanoko briskly revels in putting them in line.

For my taste, the art isn’t quite up to the standards of the writing. The best of the illustrations exist in extremes, either in the hyper-stylized bits, where Kanoko can look demonic with glee, or in the glamour shot moments, the relatively realistic close-ups of characters in the grip of emotion. The in-between stuff is mostly serviceable, never exactly bad, but it feels obvious where Tsujita has devoted the bulk of her effort.

Of course, the standards of the writing are very, very high. Tsujita isn’t content to overturn expectations just once in a story, opting to flip things around at least a few times before she’s done. And she’s really good at making harsh personalities into likeable characters without going soft. The Secret Notes of Lady Kanoko offers a great start to the year in shôjo – sneaky, funny storytelling that keeps you guessing and smiling.

Off the Shelf: Sweet Surprises

Welcome to another edition of Off the Shelf with MJ & Michelle! I’m joined, as always, by Soliloquy in Blue‘s Michelle Smith.

This week, we take a look at new releases from Viz Media and Tokyopop, as well as a continuing series fromYen Press.

MJ: Greetings from the land of mountainous snow!

MICHELLE: Salutations from the land of Floridians feeling put out because they have to wear gloves!

MJ: I hate you people.

MICHELLE: Fine. Then we’re taking back all our sweet tea.

MJ: I didn’t mean it! I didn’t mean it! Please bring back the tea!

MICHELLE: Thought so. *smugs*

MJ: So, while you’re feeling smug, wanna tell me what you’ve been reading?

MICHELLE: First up for me this week is Arina Tanemura’s Mistress Fortune, a one-shot due out from VIZ on February 1st. I haven’t had the best luck with Tanemura—early on, I enjoyed the anime version of Kamikaze Kaito Jeanne and the manga Full Moon o Sagashite, but was disappointed by the overpopulated and abruptly truncated Time Stranger Kyoko as well as what little I read of The Gentlemen’s Alliance Cross. Quite frankly, I expected not to like this.

MICHELLE: First up for me this week is Arina Tanemura’s Mistress Fortune, a one-shot due out from VIZ on February 1st. I haven’t had the best luck with Tanemura—early on, I enjoyed the anime version of Kamikaze Kaito Jeanne and the manga Full Moon o Sagashite, but was disappointed by the overpopulated and abruptly truncated Time Stranger Kyoko as well as what little I read of The Gentlemen’s Alliance Cross. Quite frankly, I expected not to like this.

At first, it seemed like I’d be right, since I rolled my eyes several times during the opening pages. The gist of the plot is thus: Kisaki is a fourteen-year-old psychic who works for a government agency fighting adorable aliens. She’s partnered with Giniro, a boy her own age, with whom she is in love but about whom she’s forbidden to ask any personal questions. Their code names are Fortune Quartz and Fortune Tiara and they focus their psychic powers by affixing cheerful star-shaped stickers to their target.

Really.

But, y’know, somehow this story managed to grow on me! I think part of it must be that Tanemura is simply better when dealing with smaller casts of characters, as in those series I mentioned liking above. Secondarily, because it’s a very relaxed, three-chapter love story it isn’t as if I went into it really expecting any sort of depth. Kisaki loves Giniro. Giniro is fixated on Kisaki’s boobs. She discovers he has angst. A very brief misunderstanding ensues. They declare their love. Spoilers? Not really; it was inevitable.

One thing that genuinely pleased me is that Tanemura’s attempts at humor are actually amusing this time. I still shudder in horror at a theoretically comical side character from Time Stranger Kyoko, but the plushie-looking alien, EBE-ko, whose dreams is to be a socialite with designer bags, is actually lively and cute. There are also a couple of fun “reaction shots” from eyewitness animals, like if something slightly naughty happens, you’ll cut to a nearby frog who says, “I saw it!”

No, Mistress Fortune is not great, but it’s certainly much better than I’d expected.

MJ: I actually read this recently as well, and my experience was very similar to yours. I started out rolling my eyes, but was mostly won over by the end, mainly thanks to the whimsical charm of EBE-ko. Though it’s a pretty shallow romance overall, it’s also very appropriate to the age of the characters and the tone of this short manga. I wasn’t wowed or anything, but I was pleasantly surprised.

MICHELLE: Exactly. It gave me some hope that Sakura Hime, Tanemura’s other new VIZ series (due April 5th), might be kind of fun. The Heian Era setting is encouraging, at least.

MJ: Agreed!

MICHELLE: Read any pleasantly surprising things this week?

MJ: Yes I did, actually! You know, despite your recommendation, I still wasn’t quite prepared for the utter sweetness that is Yuuki Fujimoto’s The Stellar Six of Gingacho.

MJ: Yes I did, actually! You know, despite your recommendation, I still wasn’t quite prepared for the utter sweetness that is Yuuki Fujimoto’s The Stellar Six of Gingacho.

For those who don’t know, the series revolves around 13-year-old Mike (pronounced “Mee-kay”) and five friends she grew up with, all from families who own food stands in a busy street market. Over the past year, as they entered middle school, the six have quietly drifted apart, each making new friends and becoming increasingly awkward with each other. Feeling the loss, Mike tries to bring the gang back together by inviting them to enter a traditional dance contest at their market’s summer festival. Though her efforts are unsuccessful at first, a mutual enemy finally puts them all on the same page.

The story is simple and not particularly suspenseful, but Mike and her friends are so likable and fun to be with, it’s a real pleasure to watch things play out.

The series’ first volume focuses mainly on Mike and her best buddy, Kuro, son of the market’s fishmonger, from whom she was inseparable until puberty came along to make their friendship more complicated. Their story is nothing new, but there’s something so fresh about the telling of it, you’d swear it was the first of its kind. The secret to this may be the fact that neither their affection nor their awkwardness is overplayed, leaving smaller moments to stand out with real poignance. A panel, for instance, in which Mike first notices that Kuro’s hands have gotten bigger than hers, is actually quite touching, though it comes and goes in the blink of an eye.

Fujimoto’s artwork is spare and not especially distinctive, though like this story, it’s surprisingly expressive. And the fact that one of the Six is a genuinely lovely, overweight girl earns about a hundred points from me.

Though the others of the Six are yet defined by fairly surface characteristics, I expect they’ll each find their moments in upcoming volumes of the series. I honestly can’t wait.

MICHELLE: Oh, I’m so glad you liked it! You mention several of the things I liked best, myself—the moment about Kuro’s hands and the overweight character who is not written off as “fat girl” and given no face or personality—and captured the appeal of the story well when you said that though the story isn’t new, something about the telling feels fresh. I do get the feeling each of the friends will receive more attention as we go along, but I like Mike a lot, so I hope we never stray too far from her perspective.

MJ: Yes, Mike is a lot of fun, and really it’s Fujimoto’s characterization of her that has me so looking forward to getting to know the other four kids. I have a lot of confidence that they’ll all be equally as special. Also, Mike and Kuro have such a sweet backstory, I feel certain we’ll see more of the bonds between the others as well.

So, what else have you got for us this week?

MICHELLE: I read the third and fourth volumes of Yana Toboso’s Black Butler. Despite some terrifically unfunny supporting characters, I’ve enjoyed this series from the beginning, but the third volume really takes things to a whole new level.

MICHELLE: I read the third and fourth volumes of Yana Toboso’s Black Butler. Despite some terrifically unfunny supporting characters, I’ve enjoyed this series from the beginning, but the third volume really takes things to a whole new level.

In this series, a thirteen-year-old named Ciel Phantomhive is the head of his family after a fire claimed the lives of his parents. To assist him in his plans for revenge he has entered into a contract with a devil who is serving him in the guise of his butler, Sebastian. The Earls of Phantomhive have always served as a “watch dog” for the crown, a duty Ciel is now expected to perform for Queen Victoria. When she sends him to London to find Jack the Ripper, he duly complies, not realizing someone from within his own family is involved.

There are probably a million historical inaccuracies in this setting, but I don’t care. I’m a sucker for Victorian England, and it’s simply a lot of fun watching Sebastian get into a fight with a chainsaw-wielding corrupt shinigami on a cobblestone street. Moreover, the change of scenery provides some respite from the entirely

incompetent servants at the Phantomhive manor.

They return in volume four, alas, along with a pretty self-proclaimed Indian prince with an impressive butler of his own. This time Ciel is in London to investigate assault crimes against Englishmen who’ve recently returned from India, but developments in the case somehow prompt the leads to contemplate entering a curry competition. I didn’t enjoy this volume as much as the third, but the emphasis on solving mysteries is pretty fun and Toboso’s art is very easy on the eyes.

MJ: I’m heartened a bit to hear your take on volume three, since I let this series go after the first two volumes which did very little for me. The third volume actually sounds like it might be genuinely fun. Maybe I’ll give it another look. Do you find yourself looking forward to the next volume?

MICHELLE: I do! In fact, I even pondered checking out the anime, which is a rare thing for me. If you’ve let the series lapse, I definitely recommend checking out at least volume three because it shows the potential of this series to become something genuinely fascinating.

MJ: I’m genuinely surprised to hear it!

MICHELLE: Now I’m genuinely hoping “fascinating” wasn’t an overstatement. I’ve at least become invested in a way I wasn’t before, which is really all one can ask for.

MJ: That’s good enough for me!

Join us again next week, when we’ll be discussing Karakuri Odette for a special MMF edition of Off the Shelf!

The Seinen Alphabet: X

“X” is for…

xxxHOLic, written and illustrated by CLAMP, originally serialized in Kodansha’s Young, now wrapping up its run in Bessatsu Shonen Magazine, and published in English by Del Rey. It’s a fairly complicated series to describe, but it’s ultimately about a young man who can see troublesome spirits and falls into the circle of a gorgeous witch.

X-Western Flash, written and illustrated by Masashi Tanaka, serialized in Kodansha’s Afternoon and Morning, three volumes total. I can only guess what it’s about, but Tanaka created Gon (CMX), so how can you not at least be curious?

Xavier Yamada no Ai no Izumi, written and illustrated by Yamada Xavier, published in four volumes by Shueisha, though I’m not sure which magazine was home to it. Again, I have no clue what it’s about, but I liked the cover.

Xenos, written and illustrated by Mio Murao, originally serialized in Akita Shoten’s Young Champion, four volumes. It’s a mystery about a reporter whose wife disappears. Murao also did a four-volume sequel, Xenos 2: Room Share, for Young Champion.

What starts with “X” in your seinen alphabet?

The Best Manga You’re Not Reading: Blue Spring

As depicted in most shojo and shonen manga, the Japanese high school is the epitome of order, with students in neat, military-style uniforms diligently studying for exams, tidying up classrooms, staging plays, and participating in cultural festivals. Students who don’t fit into the school’s established pecking order — social, athletic, or academic — quickly find themselves ostracized by their peers for lack of purpose.

Taiyo Matsumoto, however, offers a very different image of the Japanese high school in his anthology Blue Spring. His subjects are the kids with “front teeth rotten from huffing thinner,” who “answer to reason with their fists and never question their excessive passions” — in short, the delinquents. Kitano High School, the milieu these kids inhabit, is a crumbling eyesore with graffiti-covered walls, trash-filled stairwells, and indifferent faculty. Students cut class and fill their after-school hours with girlie magazines, petty crime, and smack-talk at the local diner, marking time until they join the world of adult responsibility.

Gangs, bullies, disaffected teens playing at thug life — it’s familiar territory, yet in Matsumoto’s hands, these potentially cliche stories acquire a new and strange quality. Matsumoto eschews linear narrative in favor of digressions and fragments; as a result, we feel more like we’re living in the characters’ heads than reading a tidy account of their actions. Snatches of daydreams sometimes interrupt the narrative, as do jump cuts and surreal imagery: sharks and puffer fish drift past a classroom window where two teens make out, a UFO languishes above the school campus. Even the graffiti plays an integral part of Matsumoto’s storytelling; the walls are a paean to masturbation, booze, and suicide, cheerfully urging “No more political pacts—sex acts!”

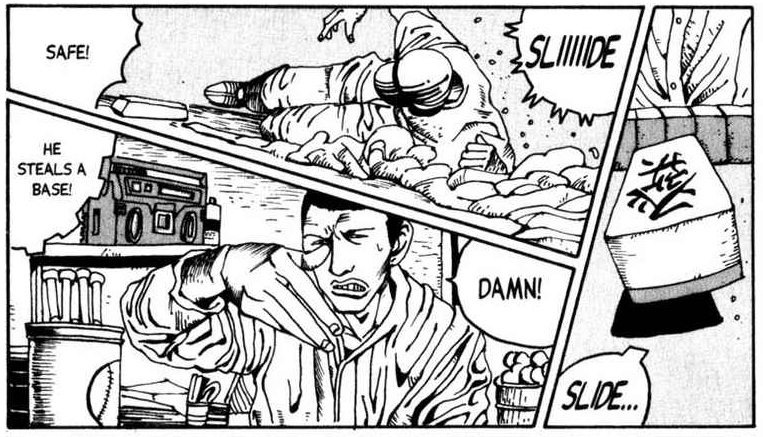

One of the most arresting aspects of Blue Spring is Matsumoto’s ability to manipulate time. In one of the book’s most visually stunning sequences, for example, Matsumoto seamlessly blends two events — a baseball game and a mahjong game — into a single sequence:

Matsumoto makes it seem as if the gambler’s action precipitated the slide into second base. It’s an elegant visual trick that establishes the simultaneity of the two games while suggesting the intensity of the mahjong play; the discarding of a tile is portrayed with the same explosive energy as stealing a base.

Matsumoto makes it seem as if the gambler’s action precipitated the slide into second base. It’s an elegant visual trick that establishes the simultaneity of the two games while suggesting the intensity of the mahjong play; the discarding of a tile is portrayed with the same explosive energy as stealing a base.

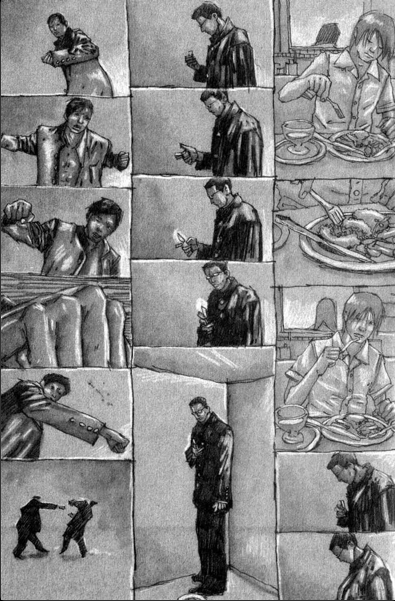

Some of Matsumoto’s time-bending sequences are more cinematic, evoking the kind of split-screen technique popularized in the 1960s by filmmakers like John Frankenheimer and Richard Fleischer. The prologue, for example, contains a series of short, vertical strips in which we see unnamed teenagers preparing for a day at school. Matsumoto deliberates re-frames the activity in each panel, drawing back to show the full scene in some, and pulling in close to reveal the blankness of a characters’ face in another:

It’s an effective montage, largely for the way it juxtaposes the banal with the violent; the fist-fight is presented in the same, matter-of-fact fashion as the student eating breakfast, suggesting that conflict is as routine for some of Blue Spring‘s characters as catching the train to school. The transitions, too, are handled deftly; the eye can process these little vignettes in a sequence while the brain grasps the entire prologue as a simultaneous collage of events, a representative cross-section of high school students going about their business on a typical day.

Matsumoto’s stark, black-and-white imagery won’t be to every reader’s taste; I’d be the first admit that many of the kids in Blue Spring look older and wearier than Keith Richards, with their sunken eyes and rotten teeth. But the studied ugliness of the character designs and urban settings suits the material perfectly, hinting at the anger and emptiness of the characters’ lives. Matsumoto offers no easy answers for his characters’ behavior, nor any false hope that they will escape the lives of violence and despair that seem to be their destiny. Rather, he offers a frank, funny and often disturbing look at the years in which most of us were unformed lumps of clay — or, in Matsumoto’s memorable formulation, a time when most of us were blue: “No matter how passionate you were, no matter how much your blood boiled, I believe youth is a blue time. Blue — that indistinct blue that paints the town before the sun rises.”

This is an expanded version of a review that appeared at PopCultureShock on 4/30/07.

BLUE SPRING • BY TAIYO MATSUMOTO • VIZ • 216 pp. • RATING: MATURE (18+)

Manhwa Monday: 12 Creators & the Milky Way

Welcome to another Manhwa Monday!

Welcome to another Manhwa Monday!

After last week’s whining about the lack of new manhwa licenses, we’ve discovered at least one, though we don’t know for sure whether there are plans to release it in print.

The December issue of Yen Plus advertises an upcoming manhwa series from Sirial (One Fine Day), called Milkyway Hitchhiking, about a cat with a pattern that looks like the Milky Way on his back. The series will be in full color, and is also Yen Press’ first simultaneous serialization. Let’s hope it sees print publication as well! Lori Henderson has some thoughts on the series in her write-up of December’s issue of Yen Plus. (Thanks to Michelle Smith for the tip!)

Robot 6 has an exclusive look at cover art for TOKYOPOP’s new Priest Purgatory series. And on the subject of Priest, 411 mania lists the upcoming film adaptation as one of its Biggest Comic Book Movies of 2011 .

iSeeToon continues their series on different types of manhwa with a look at Korean webtoons in their blog this week.

Blog of Asia attempts to explain the difference between manga and manhwa, drawing some interesting conclusions about both.

Here at Manhwa Bookshelf, Hana Lee translates the list of winners from Korea’s Reader Awards for manhwa in 2010.

This week in reviews, both Ed Sizemore of Manga Worth Reading and Richard of Forbidden Planet International take a look at Korea as Viewed by 12 Creators (Fanfare/Ponent Mon), offering a nice break from our usual cluster of Yen Press titles.

That’s all for this week!

Is there something I’ve missed? Leave your manhwa-related links in comments!

Two from Yoshinaga

One of the fascinating things about Fumi Yoshinaga’s Ôoku: The Inner Chambers (Viz) is watching the core elements of the series refine themselves. The fifth volume brings the level of emotional savagery to new heights, which is saying something.

One of the fascinating things about Fumi Yoshinaga’s Ôoku: The Inner Chambers (Viz) is watching the core elements of the series refine themselves. The fifth volume brings the level of emotional savagery to new heights, which is saying something.

In Yoshinaga’s gender-reversed imagining of the halls of power of feudal Japan, none of the shoguns have fared well in terms of emotional satisfaction. The demands of power and the palpable unease with societal reversals leave everyone at least a little undone, no matter how assiduously they try to adapt (or pretend that they’ve adapted). This time around, conniving Sir Emonnosuke, Senior Chamberlain of the Inner Chambers, continues his sly but ultimately joyless schemes, while the Shogun, Tsunayoshi, is torn between competing demands.

There’s undeniable cruelty in Tsunayoshi’s plight. She’s forced to choose between the demands of governance and succession, and her internal conflict has dire consequences for the kingdom. She’s also divided between the demands of the next generation and the previous, beholden to an elderly father wrestling with his own traumas. Since Ôoku isn’t about triumphing over adversity, readers are left to watch the spiral and marvel in the ways it spreads out, both in terms of specific character and the culture they inhabit.

By comparison, Emonnosuke’s travails seem trivial, but flashbacks provide context for his functional present. And it all contributes to the notion of the personal and political blurring beyond recognition, which really is the defining concern of the series.

Much as I love the title, it would be dishonest not to acknowledge its flaws. The adaptation is sometimes flowery, though its excesses have leveled off over time. Another issue is Yoshinaga’s sometimes repetitive character design. She definitely has aesthetic types she favors, which can make things confusing in a cast so large. (On the bright side, she favors attractive people, so at least the confusion is easy on the eye.)

On the opposite end of the Yoshinaga spectrum is Not Love But Delicious Foods Make Me So Happy! (Yen Press). This is Yoshinaga being aimlessly charming and indulging in one of her favorite obsessions, cuisine. It’s a semi-autobiographical restaurant crawl for the readers of Ohta Shuppan’s intriguing Manga Erotics F and features a Yoshinaga avatar, Y-Naga, dragging her friends and colleagues from eatery to eatery.

On the opposite end of the Yoshinaga spectrum is Not Love But Delicious Foods Make Me So Happy! (Yen Press). This is Yoshinaga being aimlessly charming and indulging in one of her favorite obsessions, cuisine. It’s a semi-autobiographical restaurant crawl for the readers of Ohta Shuppan’s intriguing Manga Erotics F and features a Yoshinaga avatar, Y-Naga, dragging her friends and colleagues from eatery to eatery.

Reviewing it is kind of like conducting a serious critical evaluation of chatty emails from a particularly funny, endearing friend. The stories benefit from already knowing and liking Yoshinaga, though I’d wager the food obsession would be an independent draw. As someone who’s read everything of Yoshinaga’s that’s available in English and yearns for someone to publish everything that isn’t, I was perfectly delighted with the book, and I find it hard to imagine the kind of person who wouldn’t be a least a little smitten.

Yoshinaga’s self-portrait is hilariously self-deprecating. The contrast between her grubby working persona to her done-up, out-on-the-town self is never not funny, and her shameless exposure of her idiosyncrasies almost certainly made me like her more. She’s unafraid to admit that she’s more than a little selfish and certainly a glutton, but those qualities make her all the more winning, just as the flaws make her entirely fictional characters more absorbing.

And the restaurant guide, while probably useless to most North American readers, is great fun, partly for the things you learn about Japanese food culture and partly for the cast of dining companions Yoshinaga assembles. The gay friend, the depressingly attractive woman friend, the too-close-for-comfort male assistant and roommate, and the rest all bring distinct and engaging qualities to the party.

Tidbits: Four by Hinako Takanaga

This installment of Tidbits is devoted to the BL stories of Hinako Takanaga! Today I’m focusing on some shorter works, but look for Little Butterfly and Challengers in future columns. A trio of one-shots is up first—A Capable Man, CROQUIS, and Liberty Liberty!—followed by the second volume of You Will Drown in Love. That series is still ongoing in Japan, where the third volume was released in July of last year. All are published in English by BLU Manga.

A Capable Man: C-

Looks are mighty deceiving with this one. Because the cover is bright and cute I expected a sweet one-volume romance, but what I got instead was a collection of short stories featuring unappealing characters.

Looks are mighty deceiving with this one. Because the cover is bright and cute I expected a sweet one-volume romance, but what I got instead was a collection of short stories featuring unappealing characters.

Things got off to a bad start when, barely a dozen pages into the first story, “I Like Exceptional Guys,” a teenager forces himself onto his childhood friend. It’s a very disturbing scene, complete with a gag for the victim. Ugh. Afterwards, the attacker (Koji) cries and apologies and aw, gee, it’s so hard to be mad at someone who’s assaulted you when they obviously love you so much! Even Koji thinks it’s weird to be forgiven so quickly.

Another problematic story is “Something to Hide,” about a teacher who’s having an affair with his student. The student is about to graduate and wants them to move in together but the teacher has reservations. Is it because he’d be betraying the trust of his student’s parents, which he has worked hard to cultivate? Nope. It’s because he’s embarrassed about his unruly hair.

The collection is rounded out by “How to Satisfy Your Fetish,” about a trainee chef with a voice fetish who gets off on provoking disgusted reactions from his instructor, and “Kleptomaniac,” about a guy who compulsively steals objects that have been used by his crush. The latter is rather dull, but the kinky former could have been fun if I wasn’t already weary of “semi-sickos,” as Takanaga herself describes these characters.

CROQUIS: B

When Nagi Sasahara—a young man who works in drag at a gay bar and is saving up for gender-reassignment surgery—seeks to augment his income by modeling for an art class, he senses something different in the gaze of a student named Shinji Kaji. Ever since the age of ten, Nagi has fallen only for guys, so he’s both accepted his sexuality and become accustomed to rejection. Kaji surprises him by returning his feelings and the two become a couple, though the fact that they make it four months into their relationship without sleeping together causes Nagi to doubt whether Kaji is really okay with the fact that Nagi is male. Frequently comedic and happily short-lived angst ensues.

When Nagi Sasahara—a young man who works in drag at a gay bar and is saving up for gender-reassignment surgery—seeks to augment his income by modeling for an art class, he senses something different in the gaze of a student named Shinji Kaji. Ever since the age of ten, Nagi has fallen only for guys, so he’s both accepted his sexuality and become accustomed to rejection. Kaji surprises him by returning his feelings and the two become a couple, though the fact that they make it four months into their relationship without sleeping together causes Nagi to doubt whether Kaji is really okay with the fact that Nagi is male. Frequently comedic and happily short-lived angst ensues.

There are things to like and to dislike about CROQUIS. First off, I love that Nagi has known he was gay since childhood and that the story makes at least a passing reference to the existence of homophobia. I also like that he and Kaji interact essentially as equals, even though Kaji is underdeveloped and Nagi has a tendency to be high-maintenance. Where the story falters, though, is in its depiction of Nagi’s reasons for wanting to undergo surgery. Does he wish to become a woman because he feels like he’s trapped in a body of the wrong gender? Nope. He just thinks that’s the only way he’ll be able to score a boyfriend.

This volume also contains a one-shot about a pair of childhood friends and their conflicting opinions on the value of wishing upon stars and a pair of stories called “On My First Love.” The latter two are actually better than the title story, in my opinion, and tell the bittersweet tale of former classmates who had feelings for each other in the past but never managed to act on them. Now both have moved on with their lives while secretly nursing painful yet precious memories. I’m a sucker for sad stories like these, so it was a treat to discover them after the pleasant but not oustanding title story.

Libery Liberty!: B+

“In a corner of Osaka, one young man lies atop a heap of trash.” That unfortunate fellow is drunken twenty-year-old Itaru Yaichi who, in the course of being discovered by a cameraman on stakeout, breaks an expensive piece of equipment belonging to a local cable TV station and finds himself heavily in debt. The cameraman, Kouki Kuwabara, agrees to let Itaru stay at his place until he can find a job. In the meantime, Itaru helps out at the station and eventually reveals what circumstances led to his present predicament.

“In a corner of Osaka, one young man lies atop a heap of trash.” That unfortunate fellow is drunken twenty-year-old Itaru Yaichi who, in the course of being discovered by a cameraman on stakeout, breaks an expensive piece of equipment belonging to a local cable TV station and finds himself heavily in debt. The cameraman, Kouki Kuwabara, agrees to let Itaru stay at his place until he can find a job. In the meantime, Itaru helps out at the station and eventually reveals what circumstances led to his present predicament.

At first, Liberty Liberty! seems like it will be cute but utterly insubstantial love story, but the narrative offers many more complexities than I initially expected. For one, before anything romantic transpires between Itaru and Kouki, they first must become friends and do so by talking about their professional goals and setbacks. Kouki was a film student when he learned that nerve damage was impairing the sight in his left eye. He thought he was through but when a friend offered him a job at the TV station, he rediscovered his passion. Similarly, Itaru had a story concept stolen (and improved upon) by an upperclassman, so a crisis of confidence made him go on a leave of absence from school.

Gradually, by working at the station and witnessing Kouki’s example, Itaru takes the first steps towards writing again. He wants to become a person he can be proud of. His feelings for Kouki develop after this point, and his accidental confession results in a pretty amusing scene:

Again, their relationship evolves slowly, largely because Kouki has been alone for such a long time (and nursing some unrequited feelings for his cross-dressing friend, Kurumi) that it takes him a while to accept the possibilities of new love. I love that both characters are vulnerable and hesitant, and that Takanaga took the time to develop the friendship between them first before bringing them to the verge of something more. And “to the verge” it is, because the story ends before the boys have done more than smooch. As a result, Liberty Liberty! perfectly deserves its Young Adult rating and would probably be a hit in a library’s manga collection.

You Will Drown in Love 2: B-

Reiichiro Shudo and Kazushi Jinnai—both employed at a fabric store, where the younger Reiichiro is the boss and Jinnai his subordinate—have been dating for a while but Jinnai is feeling uneasy. He’s unsure whether Reiichiro really loves him or is just being compliant. When Kijima from headquarters arrives to help the store get ready for a trade show, he begins to put the moves on the oblivious Reiichiro, which sends Jinnai into a tizzy.

Reiichiro Shudo and Kazushi Jinnai—both employed at a fabric store, where the younger Reiichiro is the boss and Jinnai his subordinate—have been dating for a while but Jinnai is feeling uneasy. He’s unsure whether Reiichiro really loves him or is just being compliant. When Kijima from headquarters arrives to help the store get ready for a trade show, he begins to put the moves on the oblivious Reiichiro, which sends Jinnai into a tizzy.

Even though this is written just about as well as the introduction of an aggressively sexual new love rival can be, it’s still a pretty tired plot device. In Takanaga’s hands, Kijima isn’t as over-the-top as he might otherwise have been, but he’s still more of a catalyst than a character in his own right. Scenes in which Jinnai freaks out become a bit repetitive, but once the twist comes—it’s Jinnai that Kijima is really after—it actually allows for a pretty satisfying ending.

No, the twist is not very dramatically surprising, and no, having competition doesn’t compel Reiichiro to boldly confess his love—that would be quite out of character—but it does prompt him to object to Jinnai getting close to any other man, which Jinnai happily accepts as proof at last of Reiichiro’s affections.

This may have been a somewhat disappointing volume, but I still like these characters and this setting so I’ll be back for volume three, whenever it makes its way over here.

Review copies for CROQUIS and Liberty Liberty! provided by the publisher.

Random Sunday question: alternatives

There’s been some lively discussion of reactions to the Ax anthology from Top Shelf (and here’s the solicitation for the second volume), which inspired this weekend’s query. What I’m basically wondering is what three titles in the pile of manga you’ve read do you consider alternative? I ask this with the understanding that everyone’s tastes in comics are different and that “alternative” is an entirely relative term as a result.

Since I’m using Ax as a baseline, I’ll leave it off of my list, which consists of:

- Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu, written and illustrated by Junko Mizuno, Last Gasp

- The Box Man, written and illustrated by Imiri Sakabashira, Drawn & Quarterly

- Secret Comics Japan, written and illustrated by various artists, Viz

What are your choices?