Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film Russian Ark. Both employ a similar gambit: a literary figure from the country’s past wanders through a landscape populated by real people who played pivotal roles in its modernization. In Russian Ark, the author/protagonist role is filled by the Marquis de Custine, a French aristocrat who published Empire of the Czar: Journey Through Eternal Russia in 1839, while in The Times of Botchan the role is fulfilled by Soseki Natsume (1867-1916), the defining novelist of the Meiji Restoration. Neither Ark nor Botchan employs a clear, linear narrative; both works are episodic — even, at times, picaresque — in nature as their principle characters rub shoulders with poets, composers, czars, and politicians.

Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film Russian Ark. Both employ a similar gambit: a literary figure from the country’s past wanders through a landscape populated by real people who played pivotal roles in its modernization. In Russian Ark, the author/protagonist role is filled by the Marquis de Custine, a French aristocrat who published Empire of the Czar: Journey Through Eternal Russia in 1839, while in The Times of Botchan the role is fulfilled by Soseki Natsume (1867-1916), the defining novelist of the Meiji Restoration. Neither Ark nor Botchan employs a clear, linear narrative; both works are episodic — even, at times, picaresque — in nature as their principle characters rub shoulders with poets, composers, czars, and politicians.

When we first meet Natsume, he is writing a novel called Botchan, a short, satirical work about a energetic young man who suffers from a Holden Caufield-esque desire to expose phoniness wherever he goes. Nastume hopes Botchan will help him achieve catharsis from a vague but nagging sense of anxiety brought on by the period’s social, political, and economic upheavals, from the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement to the first murmurs of suffragism.1 Though we occasionally see Natsume in his study drafting chapters, or admiring the inky paw prints left behind by his cat, much of the manga is devoted to Natsume’s travels through Tokyo, which brings him into contact with historical figures from An Jung-Geun, an activist who assassinated the Korean governor in 1909, to Hiruko Haratsuka, a feminist active in the Seito suffrage movement of the 1910s, to Lafcadio Hearn, a Western journalist whose fascination with old Japan inspired him to write Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

…

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind.

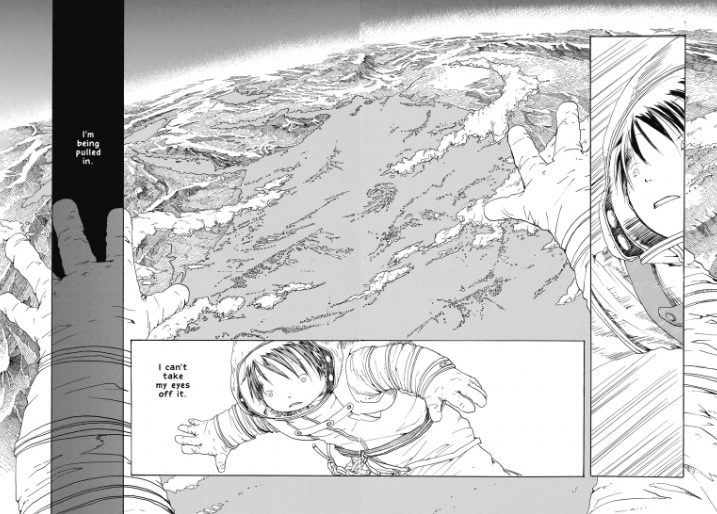

The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind. Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility.

Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility. Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power. Kobato Hanato has a job to do: if she can fill a magic bottle with the pain and suffering of people whose lives she’s improved, she’ll have her dearest wish come true. There’s just one problem: Kobato is completely mystified by urban life, and has no idea how to identify folks in need of her help. Lucky for her, Ioryogi, a blue dog with a foul mouth and fierce temper, has been appointed her sensei and guardian angel, tasked with helping Kobato develop the the street smarts necessary for completing her mission.

Kobato Hanato has a job to do: if she can fill a magic bottle with the pain and suffering of people whose lives she’s improved, she’ll have her dearest wish come true. There’s just one problem: Kobato is completely mystified by urban life, and has no idea how to identify folks in need of her help. Lucky for her, Ioryogi, a blue dog with a foul mouth and fierce temper, has been appointed her sensei and guardian angel, tasked with helping Kobato develop the the street smarts necessary for completing her mission. If you ever wondered what Freaky Friday might have been like if Jodie Foster had switched bodies with Leif Garrett instead of Barbara Harris, well, Ai Morinaga’s Your & My Secret provides a pretty good idea of the gender-bending weirdness that would have ensued. The story focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. Though Akira’s classmates find him “cute and delicate,” they declare him a timid bore — “a waste of a man,” one girl snipes — while Nanako’s peers call her “the beast” for her aggressive personality and uncouth behavior, even as the boys concede that Nanako is “hotter than anyone.” Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. With the flick of a switch, Akira finds himself trapped in Nanako’s body (and vice versa).

If you ever wondered what Freaky Friday might have been like if Jodie Foster had switched bodies with Leif Garrett instead of Barbara Harris, well, Ai Morinaga’s Your & My Secret provides a pretty good idea of the gender-bending weirdness that would have ensued. The story focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. Though Akira’s classmates find him “cute and delicate,” they declare him a timid bore — “a waste of a man,” one girl snipes — while Nanako’s peers call her “the beast” for her aggressive personality and uncouth behavior, even as the boys concede that Nanako is “hotter than anyone.” Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. With the flick of a switch, Akira finds himself trapped in Nanako’s body (and vice versa).