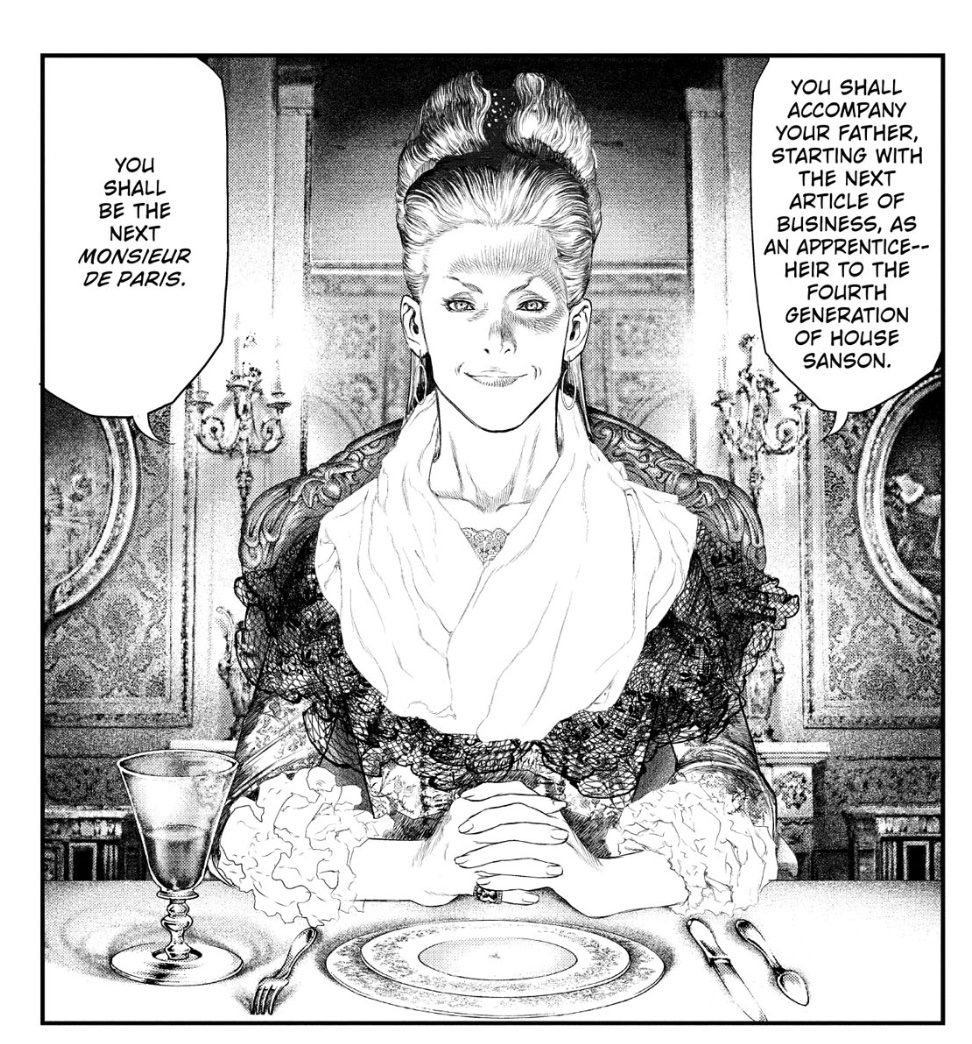

Confession is a tight, twisty thriller that reads like an episode of The Twilight Zone or Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Author Fukumoto Nobuyuki establishes the premise in a few quick strokes: two hikers—one gravely injured—huddle on a mountainside pummeled by a fierce winter storm. As they debate the best course of action, Ishikura—who is bleeding profusely—confesses to murdering a mutual acquaintance, telling Asai, “I killed Sayuri… with my own two hands.” Asai, however, refuses to abandon Ishikura, dragging his wounded friend to the safety of an abandoned cabin. As the two wait for a rescue team to arrive, it finally dawns on Asai that Ishikura might regret what he said.

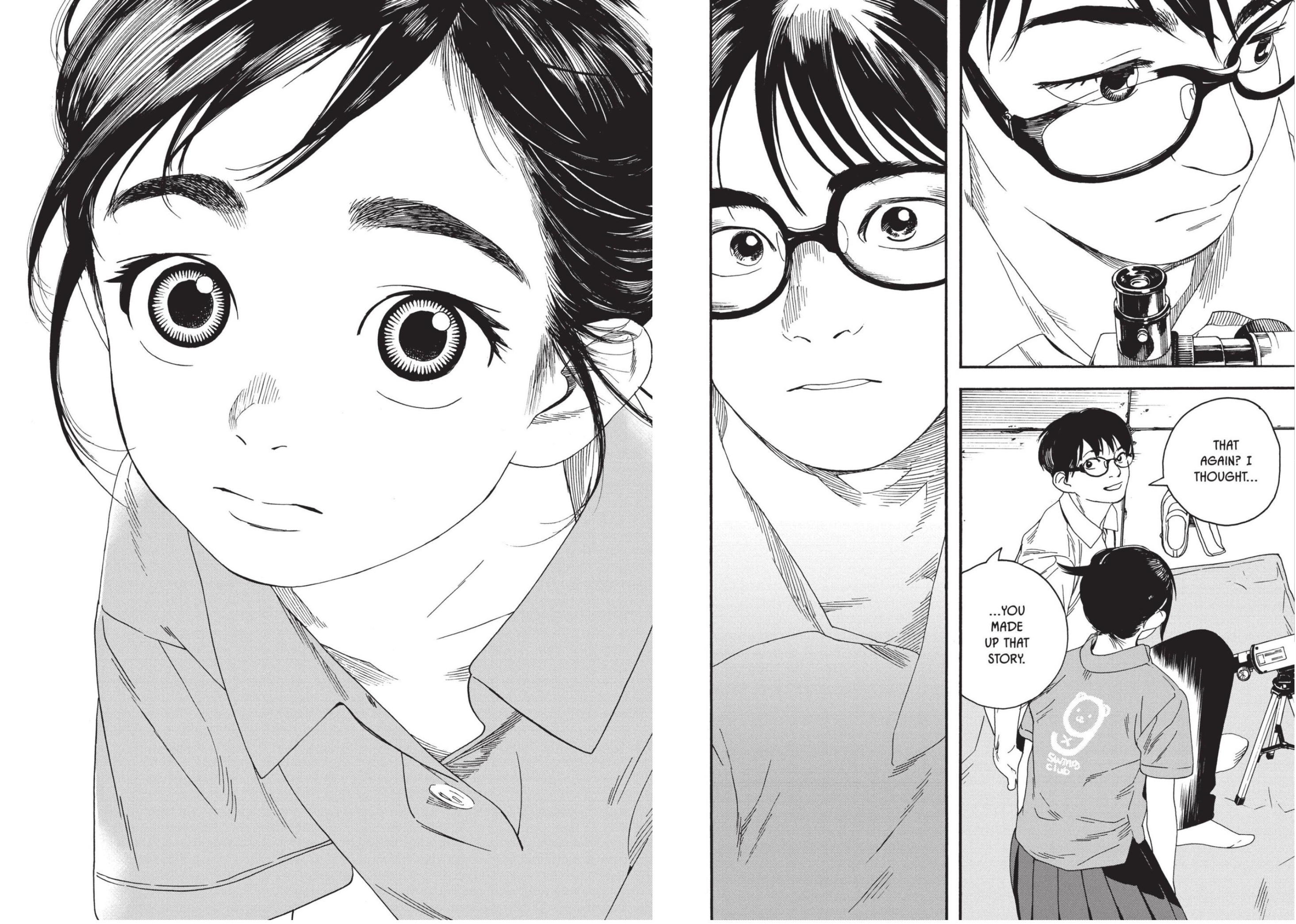

For a two-hander like this to work, it’s not enough to know what Asai is thinking; we need to feel his growing sense of desperation. Kaiji Kawaguchi’s art is up to the task, creating a spare, claustrophobic environment that’s almost as hostile as the barren slopes that surround the cabin. The cabin itself is rendered in just enough detail for the reader to grasp the layout and size, as well as the lack of good hiding places. Equally important, Kawaguchi’s character designs emphasize the wide social gap between the conventionally handsome Asai and the squat, dour Ishikura, encouraging the reader to question how these two people ever travelled in the same circles.

The artwork is so effective, in fact, that some of Asai’s internal monologue feels superfluous, especially when he states the obvious: “If my suspicions are right, are you and I going to fight to the death?” (Signs point to yes!) Aside from a few clumsy monologues, however, the story never sags under the weight of too much exposition; Nobuyuki carefully doles out information about Asai and Ishikura’s past to reveal how fraught their relationship was before they went climbing, hinting at a long-simmering conflict between them. The final scene is a shocker in the best sense, challenging the reader’s perception of both characters without cheating or taking any narrative shortcuts to get there. Hitchcock, I think, would approve. Recommended.

CONFESSION • STORY BY NOBUYUKI FUKUMOTO • ART BY KAIJI KAWAGUCHI • TRANSLATION BY EMILY BALISTERI • PRODUCTION BY TOMOE TSUTSUMI, PEI ANN YEAP, AND HIROKO MIZUNO • KODANSHA USA • RATED 16+ (VIOLENCE) • 314 pp.

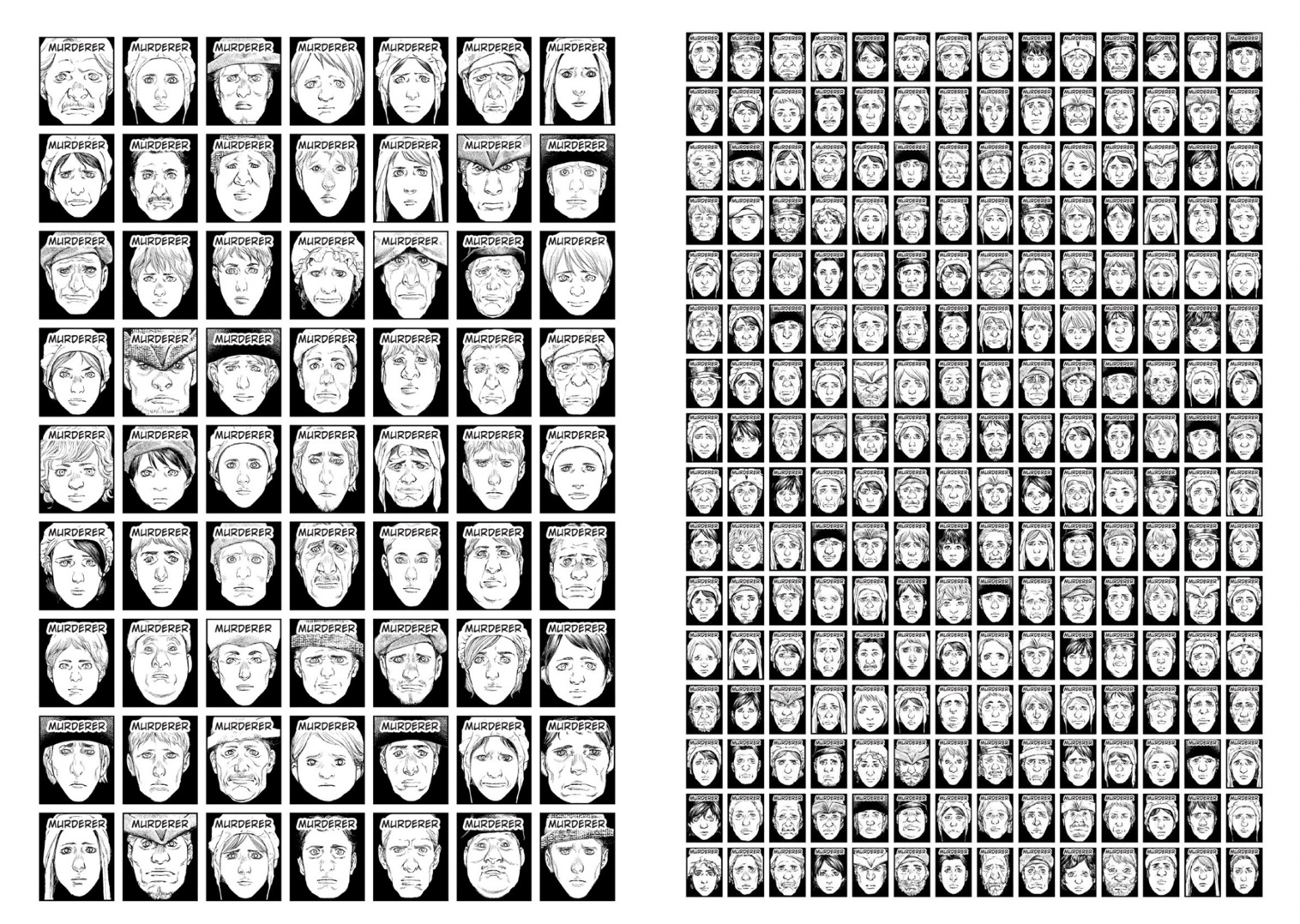

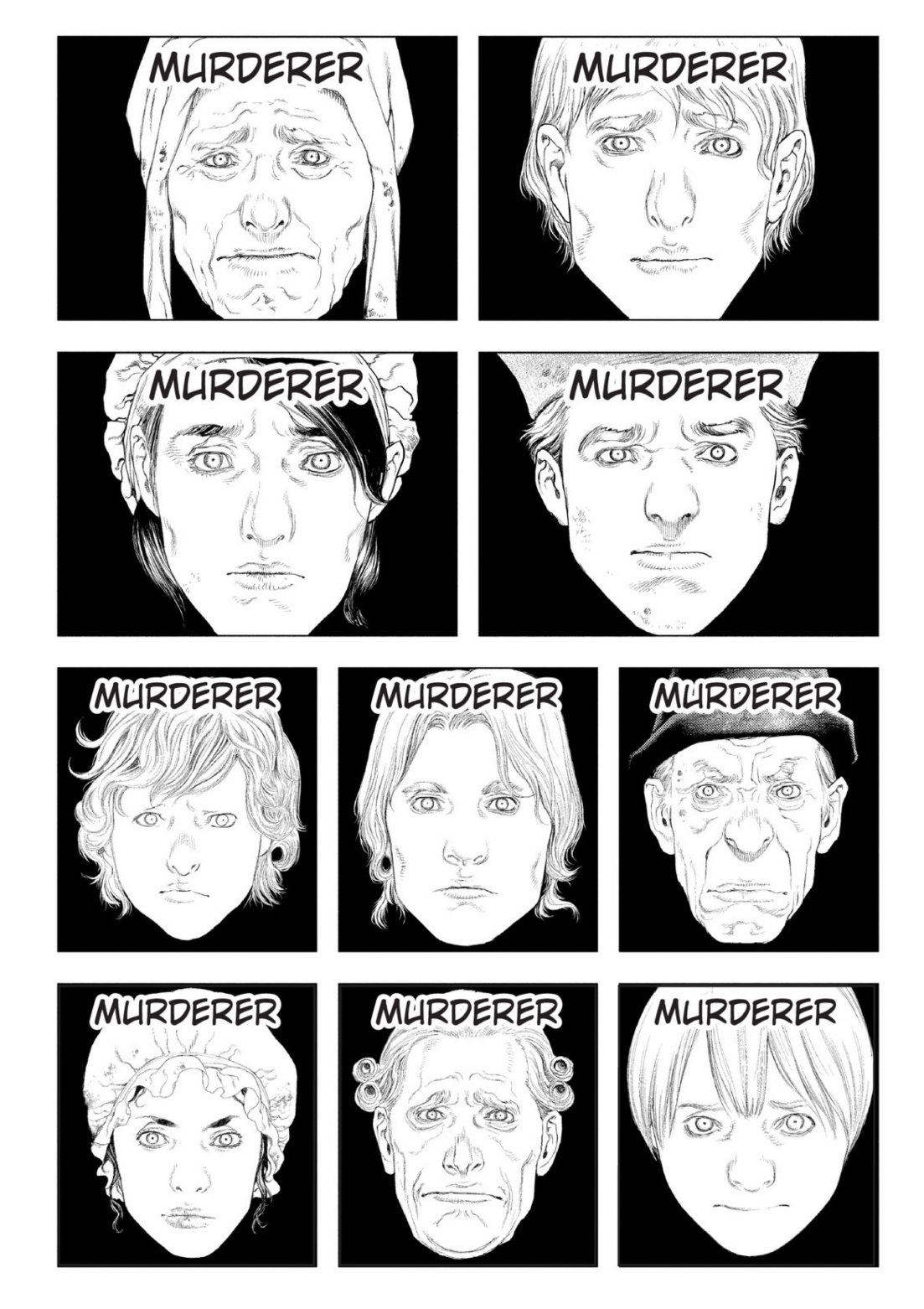

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces:

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces: