Maria Kawai, heroine of A Devil and Her Love Song, is a cool customer. Not only is she beautiful, talented, and smart, she’s also tough — so tough, in fact, that she was expelled from a hoity-toity Catholic school for beating up a teacher. Her blunt demeanor further cements her bad-girl impression; within minutes of enrolling at a new high school, she antagonizes all the girls in her class with a few sharp observations about their behavior. Only two boys — Yusuke, a cheerful, popular student who avoids conflict at all costs, and Shin, a moody outsider — try defending Maria from her peers’ nasty comments and pranks.

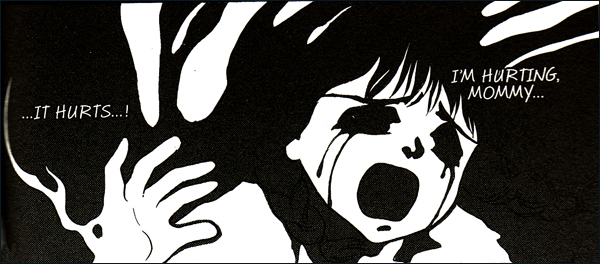

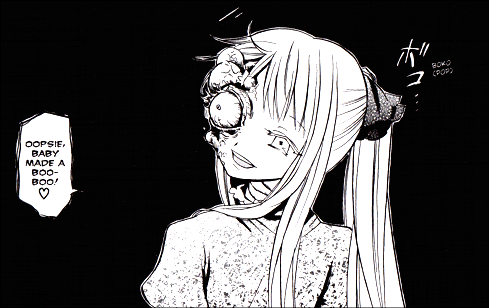

So far, so good: Maria is spiky and complicated, a truth-teller who lacks the ability to censor herself, even though she’s aware of the potential consequences of speaking her mind. Throughout volume one, there are some wonderful comic moments as Maria struggles to put a “lovely spin” — Yusuke’s term — on her acid comments. Alas, Maria’s sideways head-tilt and doe-eyed gaze look more sinister than cute; not since Kazuo Umezu’s Scary Book has a manga-ka made a doll-like character look so thoroughly menacing, even when superimposed atop a backdrop of flowers and sparkles.

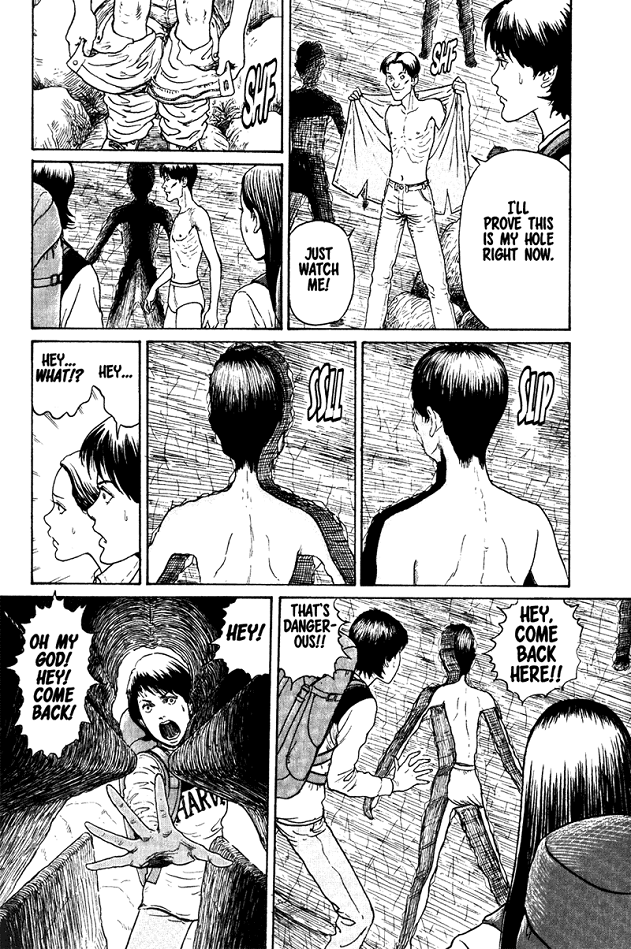

Having created such a vivid character, however, Miyoshi Tomori isn’t sure where to go with the story. In several scenes, Maria does things that contradict what we know about her: would someone as perceptive as Maria willingly attend a party hosted by the class mean girls, especially after they’d harassed her on a daily basis? And why would someone as outspoken as Maria refrain from pointing out her teacher’s judgmental behavior — especially when it’s plainly obvious to both the characters in the story and the reader? These kind of abrupt reversals might make sense if we knew more about Maria’s past, but at this stage in the story, they feel more like authorial floundering than a conscious revelation of character.

From time to time, however, Tomori convincingly hints at Maria’s softer side. Midway through volume one, for example, Maria makes tentative overtures towards Tomoya “Nippachi” Kohsaka, a fellow bullying victim. (“Nippachi” means “twenty-eight,” and is a mean-spirited reference to Tomoya’s poor academic performance.) That scene is both sad and real; anyone who’s ever seen two ostracized kids turn their classmates’ scorn on one another will immediately appreciate the dynamic between Maria and Nippachi. Maria’s exchanges with Shin, too, reveal a different side of her personality; though the pair frequently engage in the kind of rapid, antagonistic banter that’s de rigeur for romantic comedies, their quieter conversations suggest a grudging mutual respect.

Maria’s interactions with Nippachi and Shin fill me with hope that A Devil and Her Love Song will find its footing in later chapters. If Tomori can find a way to reveal Maria’s fundamental decency without compromising her heroine’s tart, outspoken personality, A Devil and Her Love Song will be a welcome addition to the Shojo Beat catalog, an all-too-rare example of a story in which the heroine isn’t the least bit concerned with being nice or popular. If Tomori can’t, Devil runs the risk of devolving into a YA Taming of the Shrew, with Shin (or, perhaps, Yosuke) playing Petruchio to Maria’s Katherina.

Review copy provided by VIZ Media, LLC. Volume one will be released February 7, 2011.

A DEVIL AND HER LOVE SONG, VOL. 1 • BY MIYOSHI TOMORI • VIZ MEDIA • 200 pp. • RATING: TEEN (13+)