Just when it seemed like none of those May TOKYOPOP titles was going to materialize, Diamond Distributors revealed that it still had a few surprises up its figurative sleeve. Stragglers, originally scheduled for an early May release, began to trickle into comic shops. I managed to acquire several, including two books—volume eight of Happy Cafe and volume three of The Stellar Six of Gingacho—that I had lost all hope of ever seeing. Although I’m still incredibly sad about TOKYOPOP’s demise, I can’t help looking upon these last releases as an unexpected gift.

Happy Cafe 8 by Kou Matsuzuki

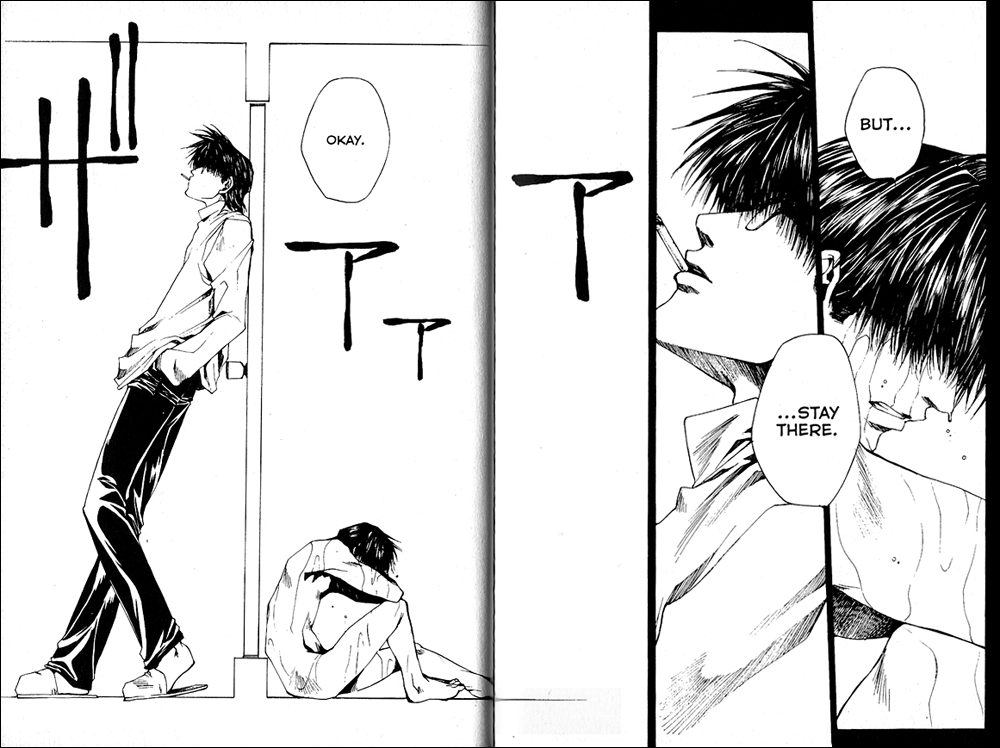

The eighth volume of Happy Cafe offers more cheerful yet insubstantial slice-of-life episodes revolving around the staff of Cafe Bonheur. We check back in with sixth-grader Kenji, Uru’s cousin, and meet the girl who likes him. We see Shindo apologize for making Uru cry, meet Ichiro’s doppelganger/father, and watch as two different guys try and fail to express their feelings for the oblivious Uru.

The eighth volume of Happy Cafe offers more cheerful yet insubstantial slice-of-life episodes revolving around the staff of Cafe Bonheur. We check back in with sixth-grader Kenji, Uru’s cousin, and meet the girl who likes him. We see Shindo apologize for making Uru cry, meet Ichiro’s doppelganger/father, and watch as two different guys try and fail to express their feelings for the oblivious Uru.

There are actually four guys now who fancy Uru, mostly because of her bright smile and talent at offering sunny advice as necessary. It’s a little much, but at least doesn’t feel as implausible as with series in which the heroine has no redeeming qualities whatsoever and yet seems to attract a bevy of hunky admirers. It also seems like Matsuzuki draws Uru in a regular style more often this volume—because she’s so childlike and spazzy, she’s usually in some state of super deformity but here we get a few, albeit fleeting, moments in which she looks genuinely pretty.

As a warning, however, readers of this volume are at risk of contracting the dreaded festitis (extreme irritability brought on by manga depictions of school festivals of any sort, including athletic). On the heels of Uru’s school festival in volume seven we first have Kenji’s athletic meet and then the school festival of Sou Abekawa, one of Uru’s suitors. I would seriously be happy if I never had to read about another school festival ever again.

So, how does this fare as the final volume (most likely) of Happy Cafe to be produced in English? Pretty well, actually. The episodic nature of the story precludes any sort of cliffhanger ending, and though Uru continues to be utterly clueless about the feelings she’s inspiring in the guys around her, it’s easy to imagine that, after several more volumes of cheerful yet insubstantial happenings, she will realize her feelings for someone (Shindo seems the most likely candidate) and a happy ending will ensue.

The Stellar Six of Gingacho 3 by Yuuki Fujimoto

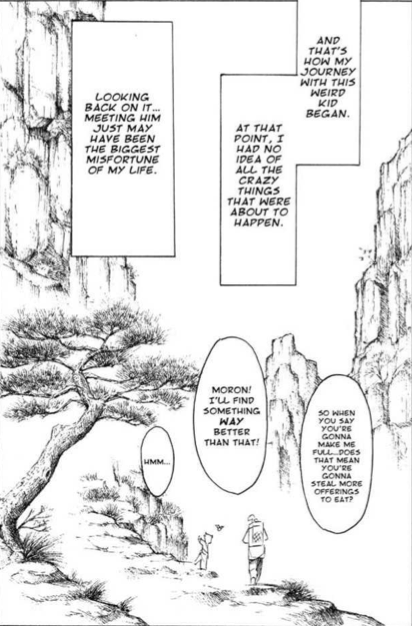

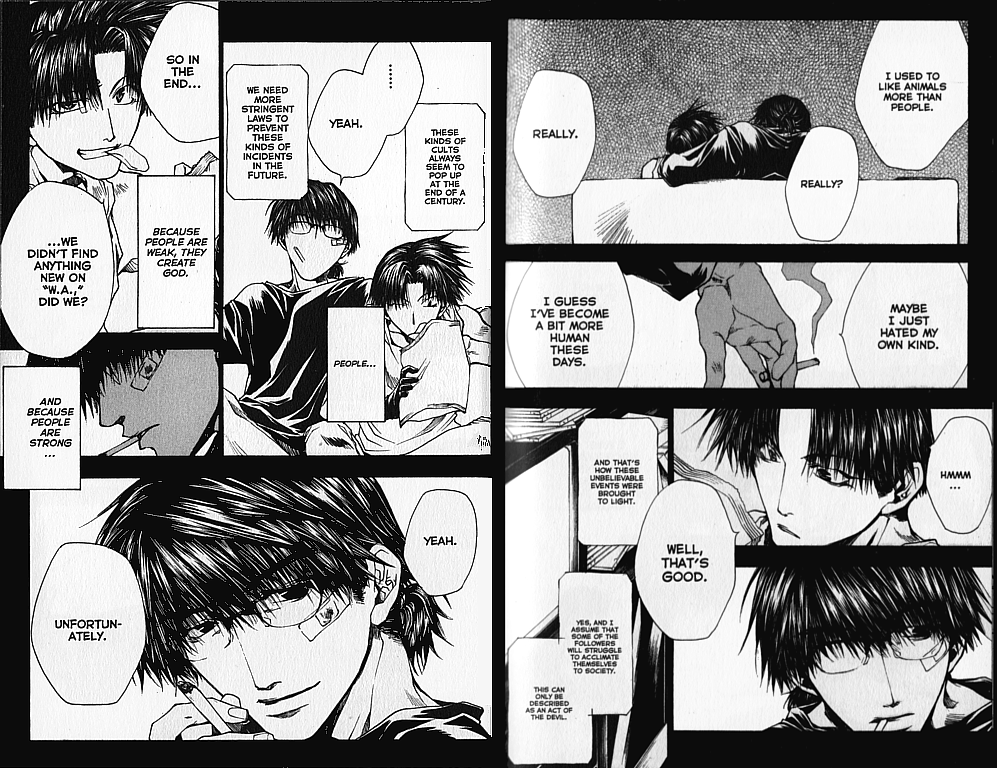

Like Happy Cafe, The Stellar Six of Gingacho has so far been comprised of warm and fuzzy episodic stories featuring a childlike heroine who is “very dense when it comes to romance.” The third volume is no different, but takes the first tentative steps at fleshing out the other members of the group—while continuing to focus on Mike (Mee-kay) and her pal/partner Kuro, whose love for Mike is a secret to no one but her—and hinting a little at complications to come.

Like Happy Cafe, The Stellar Six of Gingacho has so far been comprised of warm and fuzzy episodic stories featuring a childlike heroine who is “very dense when it comes to romance.” The third volume is no different, but takes the first tentative steps at fleshing out the other members of the group—while continuing to focus on Mike (Mee-kay) and her pal/partner Kuro, whose love for Mike is a secret to no one but her—and hinting a little at complications to come.

Chapters in this volume feature plots like “Mike and Kuro rescue a stray puppy,” “Mike insists that her friends go dig up a treasure they buried when they were five,” and “a photo of the boys appears in a teen magazine and fangirls descend.” But boiling them down in this way does them a disservice, because each chapter usually has at least one really nice moment, like Mike realizing that Kuro has always been there for her or the boys defending the honor of the girls when some punk insults them. In fact, the theme of the series could be summed up as “friends are precious and special.” If you don’t want to read stories in which this idea gets established over and over again, then The Stellar Six of Gingacho probably isn’t for you.

Although the volume doesn’t end on a cliffhanger, some glimpses of where the story might go make the lack of future releases particularly disappointing. Who is the object of ladies’ man Ikkyu’s (aka “Q”) unrequited love? (I hope it’s ultra-sensible Iba-chan.) Should I be expecting the six friends to form up into three tidy couples for a happy ending, or will messiness ensue when Sato’s feelings for Kuro come to light?

Sato provides the parting thought as we get a glimpse of an older Kuro. “To me you were special. But back then none of us truly understood what that “special” feeling really was. Not yet.” If you really want to get me hooked to a series, pepper it with retrospective narration like that. Jeez. Talk about bad timing.

1. The Fangirling – From

1. The Fangirling – From  2. The Bafflement – Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I’m baffled why a series like KimiKiss (pictured to the right) was published, or even why it might be popular. A buxom teen removing her blouse on the cover is, I expect, money in the bank! What was baffling to me in particular about this release, was that it was apparently being marketed as shoujo, according to a little pamphlet I received along with one of the later volumes of Fruits Basket.

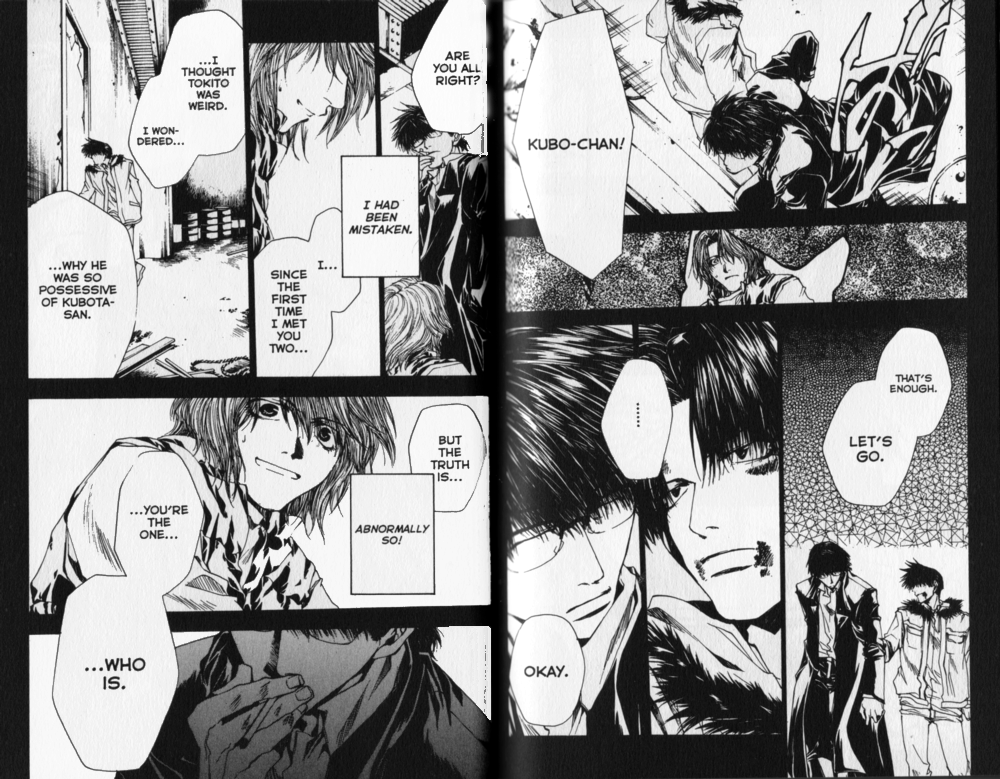

2. The Bafflement – Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I’m baffled why a series like KimiKiss (pictured to the right) was published, or even why it might be popular. A buxom teen removing her blouse on the cover is, I expect, money in the bank! What was baffling to me in particular about this release, was that it was apparently being marketed as shoujo, according to a little pamphlet I received along with one of the later volumes of Fruits Basket. 3. The Heartbreak – Everyone’s got their own tale of woe over a series that TOKYOPOP has canceled, but my broken heart belongs to Off*Beat, an almost finished series by OEL creator Jen Lee Quick. With just one volume remaining of its original 3-volume commission, fans like me were left to weep and weep, never knowing what finally happens to sweet Tory and his revealing obsession.

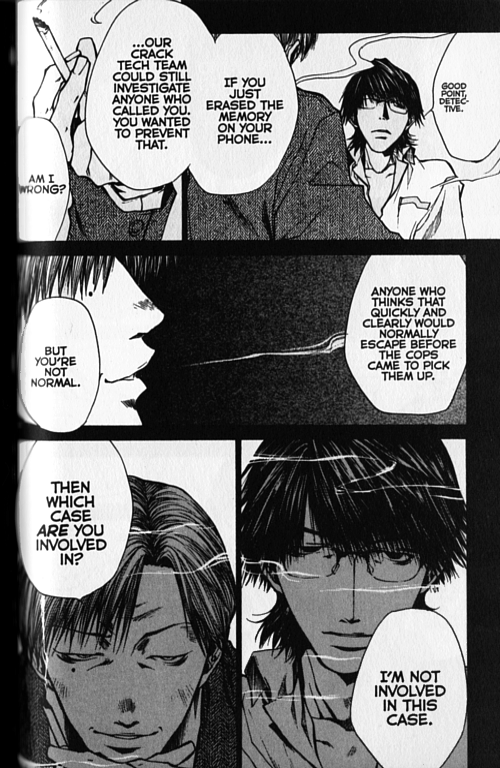

3. The Heartbreak – Everyone’s got their own tale of woe over a series that TOKYOPOP has canceled, but my broken heart belongs to Off*Beat, an almost finished series by OEL creator Jen Lee Quick. With just one volume remaining of its original 3-volume commission, fans like me were left to weep and weep, never knowing what finally happens to sweet Tory and his revealing obsession.