Have you ever seen the pilot episode of Law & Order? Most of the regular characters are present, and the script follows the three-act structure familiar to anyone who’s watched an episode of any Law & Order series, but the pacing is slack; the dialogue fizzles where it should crackle; and the actors struggle to create believable relationships between the characters, even as the script demands that they explain things to one another that, presumably, they’d already know from working together. Small wonder that “Everybody’s Favorite Bagman” languished for nearly a year before NBC rescued the show from limbo and ordered a full season of episodes.

So it is with Blue Exorcist, which has a first chapter that might charitably be described as a “pilot episode.” In these opening thirty pages, Kato introduces orphan Rin Okimura, a hot-tempered young man; Yukio, Rin’s snot-nosed fraternal twin; and Father Fujimoto, their guardian. Rin, we learn, is a direct descendant of Satan, and is in imminent danger of going over to the dark side. Father Fujimoto, however, has kept this information from his young charge, seeing fit only to explain the complexities of Rin’s lineage when Satan’s minions try to spirit Rin back to Gehenna, the demon realm. (Like all manga priests, Father Fujimoto spends more time fighting demons than preparing Sunday sermons or ministering to the sick, hungry, and bereaved.) An epic confrontation between Satan and Father Fujimoto leaves Rin’s mentor dead, forcing the boy to decide whether to cast his lot with Satan or with humanity.

There’s no reason why this opening prelude has to be such a bumpy, predictable ride, but Kato seems so intent on relating Rin’s entire Tragic Past in one installment that she trades naturalism for economy. (Sample: “I see you’ve returned. An overnight trip to the job center? How diligent of you.” And how helpful of Father Fujimoto to ask Rin a question to which he already knows the answer!) In the second chapter, however, Kato finds her stride with the material: the dialogue is looser and funnier; the characters’ relationships are more firmly and plausibly established; and she introduces her first genuinely memorable character, Mephisto Pheles. The plot is stock, with Rin vowing to avenge Father Fujimoto by enrolling in an exorcism “cram school,” but Kato enlivens the proceedings with humorous twists and nifty artwork.

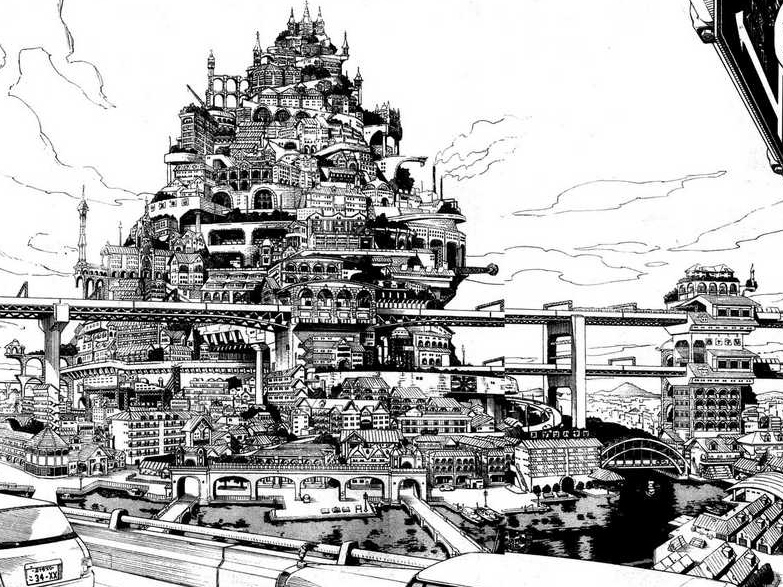

And oh, the artwork! It’s crisp and expressive, filled with small but suggestive details. Mephisto, for example, carries a patched umbrella and wears a polka-dot cravat — two minor flourishes that help establish him as a slightly decadent figure, elegant but down at the heels. The not-very-imaginatively named True Cross Town provides another instructive example of Kato’s meticulous and thoughtful draftsmanship: she lavishes considerable attention on architectural details and infrastructure, stacking layers of houses and buildings on top of one another to form a giant urban ziggeraut:

In short, Kato has created an imaginary urban landscape that seems to have evolved naturally over time, with old and new buildings side-by-side and modern modes of transport straddling canals and rivers. That kind of thoroughness may not serve much purpose in the context of a manga about demon fighters, but it lends Blue Exorcist a temporal and geographic specificity that’s sometimes missing in other areas of the story — like the religious bits.

Whatever my reservations about the first chapter, I freely admit that I’d fallen head-over-heels for Blue Exorcist by the end of the second. The brisk pacing, sharp artwork, and cheeky tone of these later chapters convinced me that Kazue Kato is in firm control of her story, and has successfully laid the foundation for the series’ first major story arc. Bring it on, I say!

BLUE EXORCIST, VOL. 1 • BY KAZUE KATO • VIZ MEDIA • 198 pp. • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)