Like many other readers who first discovered manga in the mid-2000s, TOKYOPOP played a major role in introducing me to to the medium. Tokyo Babylon was the first TOKYOPOP title I ever read, followed soon after by Legal Drug, The Legend of Chun-Hyang, and — God help me — Model, a manhwa about a Korean art student who lives in a crumbling mansion with two European vampires. (I should add that the vampires are male and the student is female, and both vampires appear to have bought their wardrobes at Hot Topic.) Though I’d be the first to admit that some of the manga I read were terrible, what I remember most about them was their romanticism: these were big, bold stories featuring impossibly beautiful characters in ridiculous situations, and I couldn’t get enough of them.

Over the years, my tastes have changed considerably, but I still feel a special allegiance to TOKYOPOP: its catalog is so large and diverse that I found plenty of other series to read when I outgrew my initial infatuation with overripe shojo. I had a hard time confining myself to just ten titles; I agonized about whether to include Mitsuhazu Mihara’s Doll, and Erica Sakakurazawa’s Between the Sheets, and Kenji Sonishi’s Neko Ramen, and Minetaro Mochizuki’s Dragon Head, all excellent series that still have pride of place in my manga library. In the end, however, I decided I had to put a cap on the number of titles to prevent my list from swelling to unmanageable proportions. Below are my ten favorite TOKYOPOP manga.

10. Jyu-Oh-Sei

10. Jyu-Oh-Sei

By Natsumi Itsuki

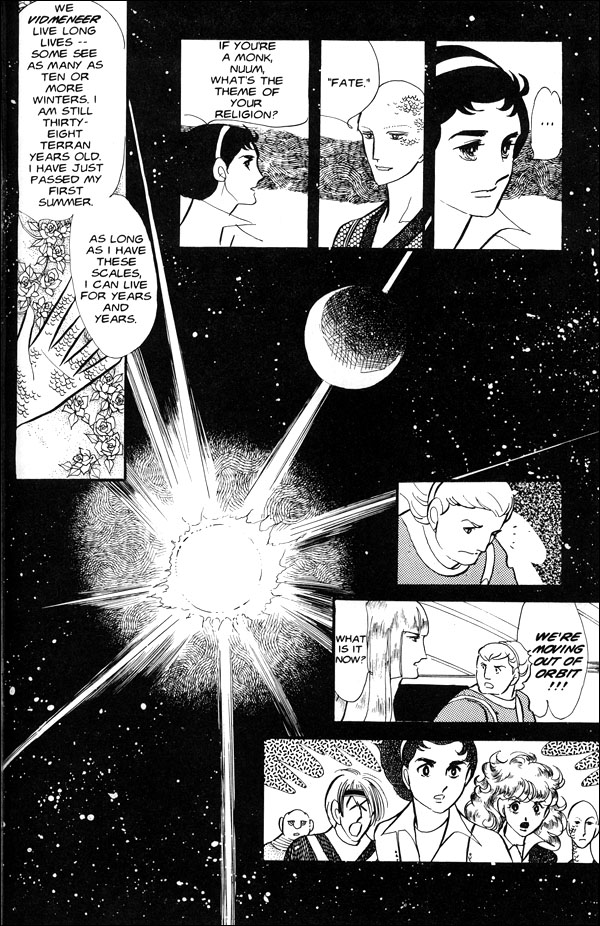

After their parents are assassinated, twin brothers Rai and Thor are exiled to the penal colony of Kimaera, where they discover extreme weather, man-eating plants, and an elaborate tribal system in which women call the shots. Their only hope of escaping the planet’s inhospitable surface is for one of them to fight his way up the social ladder to become The Beast King, or supreme ruler of Kimaera. Like Invasion of the Body Snatchers and District 9, Jyu-Oh-Sei addresses social taboos and scientific issues while serving up generous portions of what audiences crave most: action, romance, monsters, and explosions. Best of all, Jyu-Oh-Sei comes in a neat, three-volume package that’s long enough to allow for world-building and character development but short enough to stay fresh and surprising until the end. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 8/14/09

9. Petshop of Horrors

9. Petshop of Horrors

By Matsuri Akino

You won’t mistake Count D’s emporium for PETCO—the animals he sells are, in fact, demons, demi-gods, and shape-shifters who assume various guises. (One of the series’ running jokes is that some pets take human form, arousing the landlord’s suspicions that Count D actually runs a brothel.) Count D selects a pet for each customer that will help its owner realize a long-repressed dream. Of course, Count D’s services don’t come cheap; each character suffers an unexpected and often terrible consequence for seeking a magical solution to her problems. What sets Petshop apart from other examples of comeuppance theater is the writing. The characters’ plights elicit genuine sympathy from the reader; though we want these mothers and writers and lovesick twenty-something to find happiness, we can see that their own wishes are sometimes selfish, unwise, or genuinely harmful. —Reviewed at PopCultureShock on 2/13/08

8. Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

8. Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

By CLAMP

This lovely anthology is a radical departure for CLAMP. Gone are the super-detailed costumes and fussy character designs of their early, post-doujinshi work; in their place are spare, simply-drawn figures that seem consciously modeled on examples from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scroll paintings. The stories themselves are told directly without embellishment, though CLAMP infuses each tale with genuine pathos, showing us how the characters’ anger and doubt lead to profound despair. As a result, the prevailing tone and spirit are reminiscent of Masaki Kobayashi’s 1964 film Kwaidan, both in the stories’ fidelity to the conventions of Japanese folklore and in their lyrical restraint. My favorite work by CLAMP.

7. Suppli

7. Suppli

By Mari Okazaki

After being dumped by a long-term boyfriend, twenty-seven-year-old ad executive Minami carves a new identity for herself, accepting more challenging work assignments, forging friendships with her office mates, and exploring her feelings for two very different men: Ishida, a blunt co-worker with bad-boy sex appeal, and Ogiwara, a Tokyo University grad who looks great on paper, but has some nasty romantic baggage of his own. Suppli vividly and humorously evokes office life, from the unproductive meetings and grueling all-nighters to the horseplay and flirtatious banter between co-workers. The denizens of Minami’s office are colorful, if one-dimensional, characters: a salty old maid, two flamboyant karaoke fiends, and a tart-tongued temp who offers sound relationship advice to her officemates while sleeping with a married man. Anyone who’s watched Ally McBeal, The Office, or Ugly Betty has encountered these types before, but Mari Okazaki breathes fresh life into her scenario with stylish artwork, sharp dialogue, and a heroine who occasionally doubts herself, but isn’t neurotic . —Reviewed at PopCultureShock on 12/5/07

6. Cyborg 009

6. Cyborg 009

By Shotaro Ishimontori

Cyborg 009 was one of TOKYOPOP’s few forays into classic manga — a pity, because TOKYOPOP did a solid job translating and packaging Shotaro Ishimonori’s best-known work. For readers unfamiliar with this iconic series, the plot revolves around a group of people who have been kidnapped and brought to the lair of the Black Ghost organization, where surgeons transform them into robot-human fighting machines. The cyborgs soon turn on their creators and escape, intent on preventing armaggedon. I’d be the first to admit that Cyborg 009 is dated: the Black Ghost’s world-domination schemes have the same quaintly outdated ring as Dr. Evil’s, and several characters embody unfortunate gender and racial stereotypes. (As Shaenon Garrity dryly observes, “Cyborg 003 is a French girl with enhanced senses. Her duties are to hold the baby and occasionally hear things.”) Yet Ishimonori’s crisp cartooning, imaginatively staged battle scenes, and fundamental — if fumbling — humanism remain as arresting now as they did when the series first debuted in 1964.

5. Qwan

5. Qwan

By Aki Shimizu

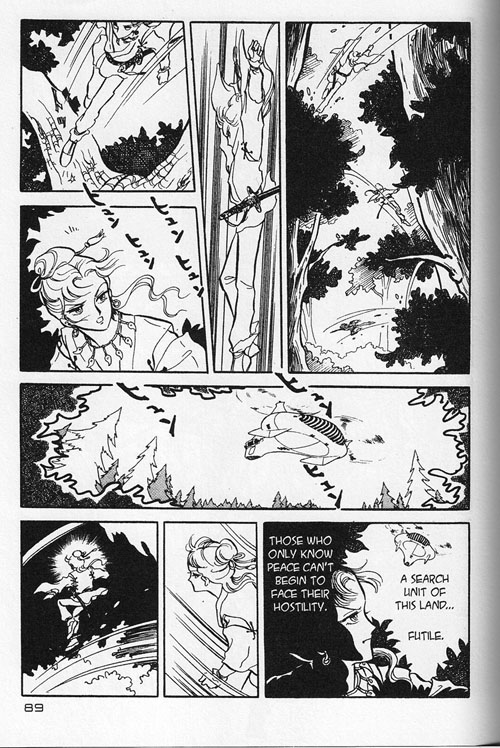

Meet Qwan, a child-like figure who possesses super-human strength and speed. Though Qwan realizes he isn’t human, he’s never questioned his origins or abilities — that is, until he meets Shaga, a courtesan who urges him to seek the Essential Arts of Peace, a sutra that will reveal where Qwan came from and why he was sent to live among humans. Questing boys and magical scrolls are de rigeur in fantasy-adventure stories, but Qwan distinguishes itself in two crucial areas: terrific characters and gorgeous artwork. Aki Shimizu’s hero is far more quirky and interesting than the typical shonen lead — Qwan never promises to do his best, or to put friends before himself — while Shimizu’s fight scenes are among the most beautifully choreographed in any licensed manga. TOKYOPOP never finished this one-of-a-kind series, but it’s still worth seeking out, if only to get acquainted with a criminally under-appreciated artist. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 3/3/11

4. Paradise Kiss

4. Paradise Kiss

By Ai Yazawa

Ai Yazawa knows how to have her cake and eat it, too: though she loves to write stories about such fantasy professions as runway model and rock star, she populates those stories with characters whose relationships and values are firmly rooted in everyday life. Consider Yukari (a.k.a. “Caroline”), the heroine of Paradise Kiss: Yukari becomes the muse for a group of aspiring fashion designers, modeling their clothing at a big design-school show and inspiring their most talented member, George, to new creative heights. In most manga, Yukari and George would bicker like teenage versions of Beatrice and Benedict until they finally admitted their mutual feelings of attraction; in Paradise Kiss, however, Yukari and George’s relationship unfolds in a more haphazard, organic way that reflects the fact that George is far more worldly and romantically experienced than Yukari. For my money, Paradise Kiss is Yazawa’s best work to date.

3. Your & My Secret

3. Your & My Secret

By Ai Morinaga

Your & My Secret focuses on Nanako, a swaggering tomboy who lives with her mad scientist grandfather, and Akira, an effeminate boy who adores her. With the flick of a switch, Akira becomes the unwitting test subject for the grandfather’s latest invention, a gizmo designed to transfer personalities from one body to another. Nanako revels in her new-found freedom as a boy, enjoying sudden popularity among classmates, earning the respect of Akira’s contemptuous little sister, and discovering the physical strength to dunk a basketball. Akira, on the other hand, finds his situation a mixed bag: for the first time in his life, his sensitive personality endears him to both male and female peers, but many of the things his maleness had previously exempted him from turn out to be much worse than he’d imagined. There are plenty of gender-bending hijinks — and the inevitable blackmail scene in which someone threatens to reveal Akira’s secret — but Morinaga still allows her characters moments of vulnerability and decency, preventing the humor from curdling into pure meanness. —Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 4/25/10

2. Tramps Like Us

2. Tramps Like Us

By Yayoi Ogawa

Twenty-eight-year-old Sumire Iwaya is frustrated: though she’s a successful journalist with degrees from Tokyo U. and Harvard, she’s hit the glass ceiling at her job and has just been dumped by her fiance. When she discovers a cute but dissheveled young man sleeping in a box outside her apartment, Sumire “adopts” him, allowing Takeshi to stay in her apartment as her “pet.” You don’t need a PhD in manga to guess the outcome of their unusual arrangement, but romantic triangles and workplace intrigue prevent Tramps Like Us from spinning into complete silliness or offensive gender stereotyping. But what really stayed with me was the depiction of Sumire’s romance with her handsome senpai Hasumi; almost every woman I know has had a relationship like theirs — perfect on paper, but stressful and unhappy in practice — and Yayoi Ogawa captures Sumire and Hasumi’s awkward dynamic in pitch-perfect detail. Now that’s good writing.

1. Planetes

1. Planetes

By Makoto Yukimura

Planetes is that rarest of manga: a human interest story that just happens to have some sci-fi trappings.Planetes focuses on a motley crew of junk collectors that includes Hachimaki, a young astronaut who aspires to join a pioneering mission to Jupiter; Yuri, a Russian astronaut with a Tragic Past; Tanabe, a sensitive but emotionally resilient trainee; and Fee, the ship’s balls-to-the-wall captain. Makoto Yukimura skillfully uses of each of his principal characters’ personal histories to explore meaty issues such as eco-terrorism, space pollution, and good old-fashioned racism. I know, I know — I’m making Planetes sound like Star Trek: Deep Space Waste Removal Station, but Yukimura is a more graceful storyteller than Gene Rodenberry every was, allowing the characters’ actions to speak louder than their words. Vivid, detailed artwork brings the terrestrial and extra-terrestrial settings to life.

* * * * *

So I turn the floor over to you: which titles were your favorites? Which ones deserve to be rescued and finished by another publisher? Inquiring minds want to know!

POSTSCRIPT, 4/20/11: Readers seeking a list of titles published by TOKYOPOP may wish to consult the ANN database entry on TOKYOPOP, the Comic Book DB entry on TOKYOPOP, or Wikipedia’s list of titles published by TOKYOPOP. I can’t vouch for their accuracy, but a quick glance at all three website suggests that these lists are comprehensive. Special thanks to all the folks on Twitter who pointed me towards these resources: @skleefeld, @yuriboke, @Funkgun, and @andrecomics.

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12 4. X-Day

4. X-Day 3. A.I. Revolution

3. A.I. Revolution 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. Love Song

1. Love Song Duck Prince

Duck Prince Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

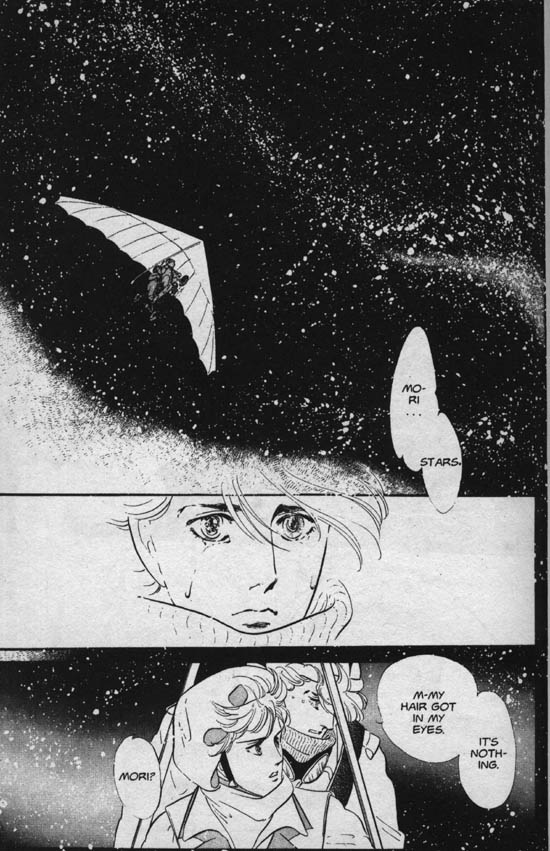

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

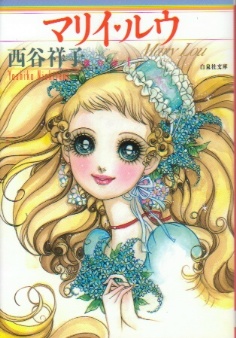

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in