Welcome to the May Manga Movable Feast! On the menu: Keiko Takemiya’s award-winning sci-fi epic To Terra. If you’ve never dined with us before, here’s how the MMF works: every month, the manga blogging community holds a week-long virtual book club in which we discuss a particular series or one-shot. Each day, the host shares links to new blog entries focusing on that work, while building an archive for the entire week’s discussion. At the end of the week, the group then selects a new host and a new “menu” for the following month.

…

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

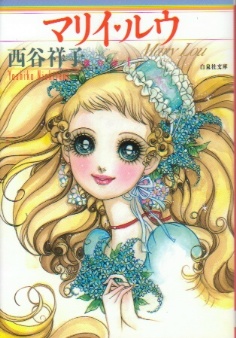

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

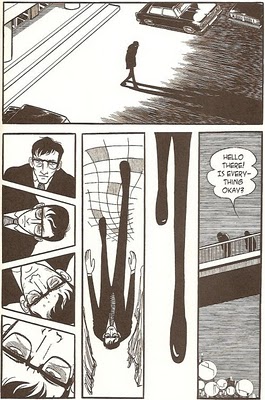

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in  “When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment.

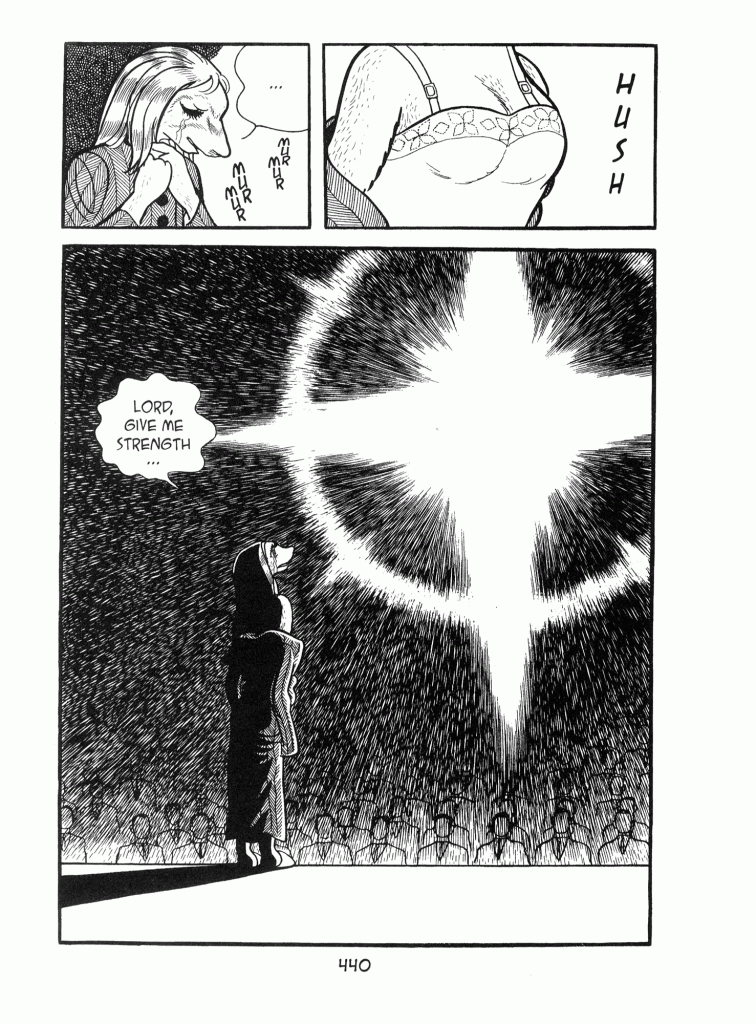

“When he heard his cry for help, it wasn’t human” — so went the tagline for Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), a bizarre fever-dream of Nietzchean philosophy, horror, and mystical hoo-ha in which a scientist’s experiments result in his spontaneous devolution. That same tagline would work equally well for Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), a globe-trotting medical mystery about a doctor who takes a similar step down the evolutionary ladder from man to beast. In less capable hands, Kirihito would be pure, B-movie camp with delusions of grandeur — as Altered States is — but Tezuka synthesizes these disparate elements into a gripping story that explores meaty themes: the porous boundaries between man and animal, sanity and insanity, godliness and godlessness; the arrogance of scientists; and the corruption of the Japanese medical establishment. At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki.

Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki.

Revisiting

Revisiting

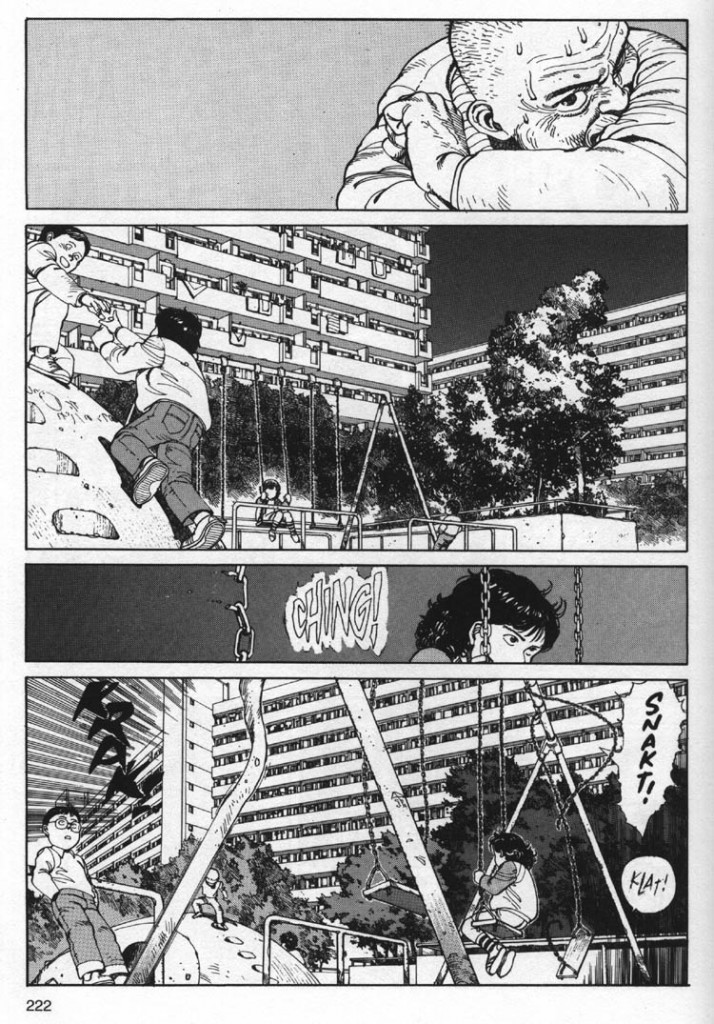

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format.

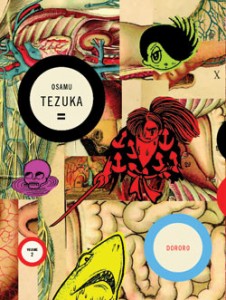

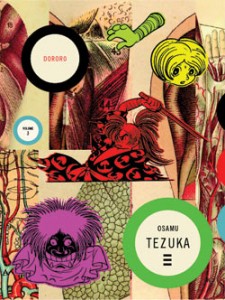

My first exposure to Katsuhiro Otomo came in 1990, when a boyfriend insisted that we attend a screening of AKIRA at an artsy theater in the Village. I wish I could say that it had been a transforming experience, one that had awakened me to the possibilities of animation in general and Japanese visual storytelling in particular, but, in fact, I found the film tedious, gory, and self-important. Little did I imagine that I’d be reviewing AKIRA nineteen years later, let alone in its original graphic novel format. If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,

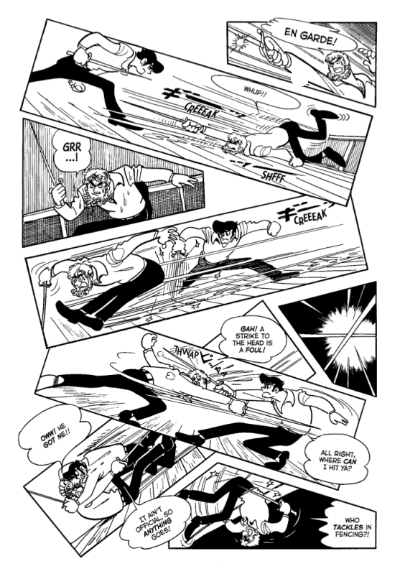

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,  Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished.

Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished. For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear.

For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear. Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.