In a scene that would surely please Jack Kirby, One-Punch Man opens with a pow! splat! and boom!, as Saitama, the eponymous hero, goes mano-a-mano with the powerful Vaccine Man, a three-story menace with razor-sharp claws. Though Vaccine Man is formidable, he has a pronounced Achilles’ heel: chattiness. “I exist because of humankind’s constant pollution of the environment!” he tells Saitama. “The Earth is a single living organism! And you humans are the disease-causing germs killing it! The will of the earth gave birth to me so that I may destroy humanity and their insidious civilization!” Vaccine Man is so stunned that Saitama lacks an equally dramatic origin story that he lets down his guard, allowing Saitama to land a deadly right hook.

And so it goes with the other villains in One-Punch Man: Saitama’s unassuming appearance and matter-of-fact demeanor give him a strategic advantage over the preening scientists, cyborg gorillas, were-lions, and giant crabmen who terrorize City Z. Saitama’s sangfroid comes at a cost, however: the media never credit his alter ego with saving the day, instead attributing these victories to more improbable heroes such as Mumen Rider, a timid, helmet-wearing cyclist. Even the acquisition of a sidekick, Genos, does little to boost Saitama’s visibility in a city crawling with would-be heroes and monsters.

If it sounds as if One-Punch Man is shooting fish in a barrel, it is; supermen and shonen heroes, by definition, are a self-parodying lot. (See: capes, spandex, “Wind Scar.”) What inoculates One-Punch Man against snarky superiority is its ability to toe the line between straightforward action and affectionate spoof. It’s jokey and sincere, a combination that proves infectious.

Saitama is key to ONE’s strategy for bridging the action/satire divide: the character dutifully acknowledges tokusatsu cliches while refusing to capitulate to the ones he deems most ridiculous. (In one scene, Saitama counters an opponent’s “Lion Slash: Meteor Power Shower” attack with a burst of “Consecutive Normal Punches.”) ONE’s script is complemented by bold, polished artwork; even if the outcome of a battle is never in question, artist Yusuke Murata dreams up imaginative obstacles to prevent Saitama from defeating his opponents too quickly, or rehashing an earlier confrontation.

Is One-Punch Man worthy of its Eisner nomination? Based on what I’ve read so far, I’d say yes: it’s brisk, breezy, and executed with consummate skill. It may not be the “best” title in the bunch–I’d give the honor to Moyocco Anno’s In Clothes Called Fat–but it’s a lot more fun than either volume of Showa: A History of Japan… Scout’s honor.

The verdict: Highly recommended.

One-Punch Man, Vols. 1-2

Story by ONE, Art by Yusuke Murata

Rated T, for teens

VIZ Media, $6.99 (digital)

This review originally appeared at MangaBlog on June 12, 2015.

Until Olivia mentioned it over in the

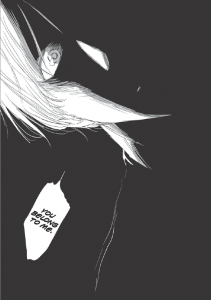

Until Olivia mentioned it over in the  I love series like this, where the leads have episodic disturbances that they investigate (via the partnership they strike up as a sort of supernatural cleaning crew and frequently assisting a non-believing cop named Hanzawa) plus an ongoing mystery (involving curses cast by someone named Erika Hiura) and yet the most important and fascinating aspect is the relationship between the leads themselves. There are the fun, suggestive moments where the guys are combining their powers for one reason or another and end up using dialogue like, “Do you want me to touch it?” or “Take me all the way in.” But where Yamashita-sensei really excels is at teasing out threads of darkness.

I love series like this, where the leads have episodic disturbances that they investigate (via the partnership they strike up as a sort of supernatural cleaning crew and frequently assisting a non-believing cop named Hanzawa) plus an ongoing mystery (involving curses cast by someone named Erika Hiura) and yet the most important and fascinating aspect is the relationship between the leads themselves. There are the fun, suggestive moments where the guys are combining their powers for one reason or another and end up using dialogue like, “Do you want me to touch it?” or “Take me all the way in.” But where Yamashita-sensei really excels is at teasing out threads of darkness.

It’s only at the end of volume three, wherein Hiyakawa nonchalantly suggests that it’d be good if they could work the other side of the business, too, that Mikado realizes he has no idea what kind of person he’s working with. As a reader, I too was lulled into believing that of course the protagonist of a series about fighting the supernatural is a good guy. Turns out, he’s more of an empty-inside opportunist. At this point, even I just want to say, “Run away, Mikado! Run away and don’t look back!” Is there any hope that he can help heal and humanize Hiyakawa, or will he only end up destroyed? How soon until volume four comes out?!

It’s only at the end of volume three, wherein Hiyakawa nonchalantly suggests that it’d be good if they could work the other side of the business, too, that Mikado realizes he has no idea what kind of person he’s working with. As a reader, I too was lulled into believing that of course the protagonist of a series about fighting the supernatural is a good guy. Turns out, he’s more of an empty-inside opportunist. At this point, even I just want to say, “Run away, Mikado! Run away and don’t look back!” Is there any hope that he can help heal and humanize Hiyakawa, or will he only end up destroyed? How soon until volume four comes out?! After making a social blunder at school that results in being shunned by her female classmates, Komugi Kusunoki is glad of the chance to start over in Hokkaido when the demands of her mother’s job mean Komugi will need to live with her father instead. At Maruyama High School, she quickly befriends a couple of nice girls (Kana and Keiko) and learns about the small clique of hotties over whom many girls swoon but who keep to themselves. One day, she surprises one of the boys (Yu Ogami) while he is napping and he turns into a wolf who promptly boops her on the nose.

After making a social blunder at school that results in being shunned by her female classmates, Komugi Kusunoki is glad of the chance to start over in Hokkaido when the demands of her mother’s job mean Komugi will need to live with her father instead. At Maruyama High School, she quickly befriends a couple of nice girls (Kana and Keiko) and learns about the small clique of hotties over whom many girls swoon but who keep to themselves. One day, she surprises one of the boys (Yu Ogami) while he is napping and he turns into a wolf who promptly boops her on the nose.  As Komugi gets to know them better, she learns that Ogami is half human and was abandoned in the woods by his human mother. Although he doesn’t hate humans as Fushimi claims to do, and is in fact kind and sweet, he’s still determined that he is going to be the last of his line and that he won’t fall in love with anyone, which is a problem because it doesn’t take long for Komugi to fall for him. Meanwhile, Fushimi witnesses this happening and tries to spare her hurt, and when she’s later trying to acclimate to just being friends with Ogami, he’s the one who’s there for her to talk to, sparking some jealous feelings on Ogami’s part.

As Komugi gets to know them better, she learns that Ogami is half human and was abandoned in the woods by his human mother. Although he doesn’t hate humans as Fushimi claims to do, and is in fact kind and sweet, he’s still determined that he is going to be the last of his line and that he won’t fall in love with anyone, which is a problem because it doesn’t take long for Komugi to fall for him. Meanwhile, Fushimi witnesses this happening and tries to spare her hurt, and when she’s later trying to acclimate to just being friends with Ogami, he’s the one who’s there for her to talk to, sparking some jealous feelings on Ogami’s part.